| Summary In almost a third of patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection presents as an acute illness (fatigue, arthralgia, jaundice) but the majority are asymptomatic. After acute infection, up to 45% of young, healthy patients can develop potent antibodies and a cell-mediated immune response, leading to spontaneous eradication of the virus. However, most infected patients fail to clear the virus. This results in chronic infection and progressive liver damage. |

How common is it?

Hepatitis C appears to be endemic in most of the world. It is estimated that the total global prevalence is around 1.6%, corresponding to 115 million previous viraemic infections; the incidence and prevalence of infection has considerable geographic, age and genotypic variation.

In some parts of the world, prevalence can be as high as 5-15% and different regions have a different risk profile and age. The prevalence is higher in specific populations such as incarcerated or institutionalized people.

What is the cause?

HCV is an infectious hepatotropic virus belonging to the Flavivirus family that is transmitted by percutaneous exposure to blood. The most common cause worldwide is unsafe injection practices during medical treatment.

Infection is also common in people who inject drugs. Less commonly it is spread through sexual activity, the perinatal period, intranasally, or after accidental contact with blood (e.g., hemodialysis).

Blood and blood products not screened for HCV have also been sources of infection. About 10% of people with HCV infection have no recognized risk factor.

Some patients, particularly younger women, clear the virus spontaneously but most people develop a chronic infection. Black people appear to be the most likely to spontaneously clear the virus.

How is it presented?

Patients are generally asymptomatic but may present with signs of decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

♦ Acute infection

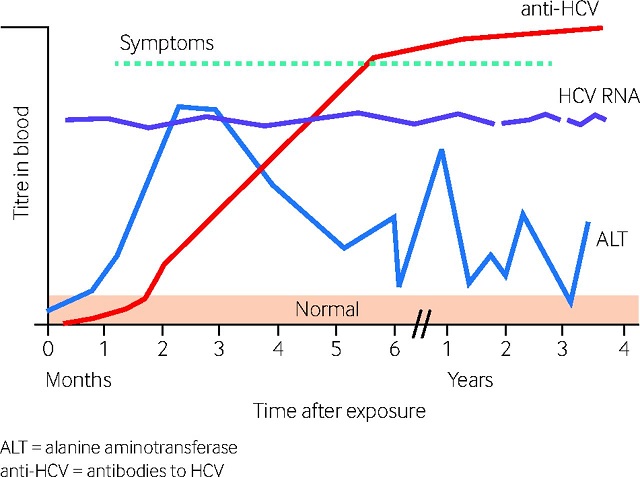

After initial exposure to the virus, most patients are asymptomatic. About 30% have characteristic symptoms and signs such as fatigue, arthralgia or jaundice associated with a transient increase in serum aminotransferases, particularly alanine aminotransferase, but fulminant liver failure is extremely rare.

♦ Chronic infection

Chronic hepatitis C infection is generally defined as the persistence of HCV RNA in the blood for at least 6 months. Patients are generally asymptomatic but may present with signs of decompensated cirrhosis (such as jaundice, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy) or hepatocellular carcinoma. Occasionally, patients may present with extrahepatic manifestations (such as vasculitis, renal complications, and porphyria cutanea Tarda).

Factors that influence the development of chronic liver disease are older age at the time of infection and male sex. Chronic hepatitis B, HIV infection, or heavy alcohol consumption also increase the risk of progressive liver disease.

In a prospective study of patients with advanced hepatitis C-related liver disease, regular coffee consumption was associated with slowing disease progression. Consuming more than 2 cups of caffeinated coffee daily is associated with a reduction in the histological activity (inflammation) of chronic HCV. Daily cannabis use is strongly associated with severe fibrosis and steatosis.

How is hepatitis C diagnosed?

Diagnostic tests for HCV are used to establish the diagnosis, prevent infection by screening donor blood, and make decisions about the medical management of patients.

What you need to know |

♦ Acute infection

HCV RNA testing is necessary to diagnose acute infection. Acid testing includes reverse transcription followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), branched-chain DNA analysis, and transcription-mediated amplification (TMA). A positive result indicates the presence of active infection. There is no preferred nucleic acid test but the most sensitive is AMT.

However, most providers use PCR because it is more readily available. It is important to remember that 15-45% of exposed people eventually eliminate the virus without treatment. In these patients, the HCV antibody test will remain positive, but the patients are no longer viremic and the nucleic acid test will become negative.

Changes in blood titers of HCV infection markers over time. (adapted from Newfoundland and Labrador Public Health Laboratory. HCV RNA (HCV RNA nucleic acid amplification test). ALT : alanine aminotransferase. Anti-HCV : anti-HIV antibodies

Changes in blood titers of HCV infection markers over time. (adapted from Newfoundland and Labrador Public Health Laboratory. HCV RNA (HCV RNA nucleic acid amplification test). ALT : alanine aminotransferase. Anti-HCV : anti-HIV antibodies

♦ Chronic infection

≈ Antibody tests

After exposure to the virus, it may take several weeks for anti-HCV antibodies to develop. Furthermore, patients can spontaneously shed the virus, up to 12 weeks after an acute exposure (such as a contaminated needle injury).

Therefore, a screening test such as the enzyme immunoassay (EIE) may be negative and should be repeated after 3 months. All patients with HCV infection should have viral genotyping done before starting treatment, in order to determine the most appropriate therapeutic regimen.

An EIE screening test detects antibodies to the virus. The same nucleic acid tests used for acute infection confirm viremia in a patient with a positive EIE or evaluate the effectiveness of antiviral therapy. A positive result indicates active infection.

An occasional false negative result may occur in immunocompromised or dialyzed patients. False positive results may occur in patients with an autoimmune disease. Suspected false positive or negative results should also prompt HCV RNA testing.

≈ Liver function tests

The physical examination or laboratory values alone may not indicate disease until it reaches an advanced stage. Serum aminotransferases, particularly alanine aminotransferase, can be used to measure disease activity, although their sensitivity and specificity are low.

≈ Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is not used to diagnose hepatitis C, but is useful in staging fibrosis and the degree of liver inflammation. However, because direct-acting antiviral therapy is currently considered very effective, biopsy is rarely justified. Another potential reason to obtain a biopsy is to evaluate the possibility of cirrhosis and thus initiate a surveillance program for hepatocellular carcinoma.

≈ Other non-invasive tests

The standard of care for predicting fibrosis compared with liver biopsy is noninvasive testing. In Europe, non-invasive tests such as elastography have become more accepted as substitutes for liver biopsy. However, elastography alone is not adequate to rule out or confirm fibrosis.

How is hepatitis C managed?

The goal of antiviral treatment is to eliminate the virus from the blood. Treatment is also associated with stabilization or even improvement of liver histology and clinical evolution. Other goals are symptom control and prevention of progressive liver disease, including cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

♦ Acute infection

There is no specific treatment for acute exposure until viremia has been established. If the physician and patient decide that delaying initial treatment is acceptable, the patient should be monitored for a minimum of 6 months for spontaneous clearance of the virus. If this occurs, then antiviral treatment is not necessary.

The treatment applied during the first 6 months is the same as for chronic infection. HCV RNA should be monitored for at least 12-16 weeks to allow time for spontaneous clearance before initiating treatment. If HCV RNA is not detected within 12-16 weeks after exposure it is unlikely that the patient has been infected or has experienced spontaneous clearance of the virus.

♦ Chronic infection

Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend treatment for all HCV-infected patients, except those with a short life expectancy (e.g. , comorbidities). Studies show that treatment early in the disease is associated with better outcomes compared to waiting until the disease develops.

Interferon therapeutic regimens are not currently recommended for HCV infection as first-line therapy now uses the newer oral direct antiviral agents. Up to 30% of HCV-infected patients treated with interferon develop major depression.

A 12-year population cohort study found that HCV-infected patients with a history of interferon-induced depression had a significantly increased risk of recurrent depression, even without additional exposure to interferon α. The use of antidepressants during treatment with interferon α does not reduce the risk of recurrence.

The rapid development of new antiviral agents has generated changes in treatment guidelines, and therapeutics are now based on direct-acting antiviral agents (DALYs). Before selecting the most appropriate treatment, a specialist should be consulted. Specific regimens depend on HCV genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

Current treatments for hepatitis C infection • Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir • Elbasvir/grazoprevir combination • Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir combination • Combination of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with or without dasabuvir • Sofosbuvir plus simeprevir • Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir combination |

Emerging treatments for hepatitis C infection • Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir combination • Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir combination (glecaprevir is a protein 3/4A protease inhibitor. Pibrentasvir is an NS5A inhibitor • Second generation NS5a inhibitors (other than velpatasvir). • Alternative daclatasvir regimens. • Other treatments. |

A 2017 Cochrane review of 138 randomized clinical trials (25,232 patients) comparing DALYs with no intervention or placebo, alone or with co-interventions, found that DALYs have primarily short-term studies, and as a surrogate outcome, responses important virological There is little or no data on the effect of DALYs on hepatitis C-related morbidity or mortality.

The introduction of DALYs into HCV therapeutic regimens means that there is an increased risk of interaction with other drugs the patient may be receiving (antiretrovirals, anticonvulsants, antifungals, corticosteroids, statins, antibiotics, herbal medicines). There is also a small risk of hepatitis B reactivation.

What is the prognosis for treated patients with chronic infection?

Mortality is increasing and the number of US deaths related to HCV currently exceeds the number of deaths from HIV/AIDS. The number of deaths from HCV was 19,659 in 2014 (5 deaths/100,000 inhabitants), mainly in patients aged 55 to 64 years (25 deaths/100,000 inhabitants or 50.9% of all deaths). The mortality rate was approximately 2.6 times higher for men than for women.

Sustained virologic response (SVR) is defined as undetectable virus in serum 3 months after completion of treatment that correlates well with long-term virus freedom. A systematic review found high SVR rates for all FDA-approved treatments.

SVR rates were >95% in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection for most population combinations. Overall rates of serious adverse events and treatment discontinuation were low (<10%) in all patients.

It is prudent to abstain from alcohol, maintain ideal body weight, take prophylaxis against hepatitis A or B (through vaccination) and HIV through safe sex.

As in treatment-naïve patients, treated patients vary by HCV genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis. However, it also depends on the previous regimen you received that was not effective.

Can hepatitis C be prevented?

Clean needles and needle exchange for intravenous drug users have been able to decrease the risk of HCV transmission. Although sexual transmission of HCV is very inefficient, safe sex is a reasonable precaution in people with multiple partners and in those infected with HIV. Disposable medical and dental equipment should be used during medical and dental procedures. The risk of acquiring HCV from unsafe medical practices is very low in developed countries.

Should screening for hepatitis C be done in the general population?

Screening tests may be different between countries and, in particular, developed countries may have different practices than those used in developing countries that have limited medical facilities. Local guidance should be followed.

For example, babies born in countries where there is a high risk of medical transmission should be tested for HCV. The US Preventive Services Task Force had recommended against routine screening for HCV infection but now recommends screening for people at high risk of infection.

The US National Institutes of Health recommends screening for groups at high risk of infection, including injection drug users and prisoners. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends screening in refugees, as part of the routine medical examination of new arrivals.

In the US, screening by birth cohort (e.g., the cohort consisting of all people born between 1945 and 1965) is recommended; This approach appears to be cost-effective.

The CDC recommends one-time screening for anyone born between 1945 and 1965, as this is a population with a disproportionately high prevalence of HCV infection. This recommendation may not apply to other countries, as specific screening approaches will depend on epidemiology.