The ingestion and digestion of food is a vital function, which is controlled by the interaction between the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and the brain. Hormonal and neuronal signals from the GIT are key players in this bidirectional signaling pathway. When food is absent from the GIT, hunger signals are generated and food intake is stimulated.

In contrast, when food is present in the GIT, satiety signals will override hunger signals and food intake will be inhibited. Disruption of the delicate balance between hunger and satiety signals induces an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure that can lead to weight gain or loss.

Hunger is expected to be maximum before the start of the meal. During the meal, hunger decreases and satiety increases, contributing to the decision to discontinue food intake. Immediately after the meal, hunger is expected to be absent and satiety to be maximum. The cycle restarts with the return of hunger and the fading of satiety in preparation for the next meal.

Different processes controlled by the GIT can contribute to two crucial aspects of food intake control:

- Determination of the amount of food eaten during a meal.

- Determination of the return of hunger and the ingestion of the next meal.

The last decade has seen several publications on how the GIT detects the absence, presence and quantity of nutrients and how this impacts food intake. Based on this progress, it seems timely to take stock by assessing current understanding and identifying issues of uncertainty that indicate directions for future research.

Background

Different peripheral pathways are involved in the regulation of the food ingestion-digestion cycle.

Methods

Narrative review on the gastrointestinal mechanisms involved in satiety and hunger signaling.

Results

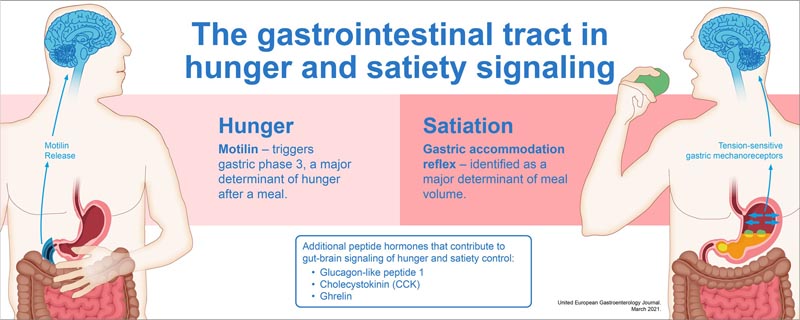

Combined mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors, peripherally released peptide hormones, and neural pathways provide feedback to the brain to determine sensations of hunger (increased energy intake) or satiety (cessation of energy intake) and regulate human metabolism.

The gastric accommodation reflex, which consists of a transient relaxation of the proximal part of the stomach during food intake, has been identified as an important determinant of food volume, through the activation of tension-sensitive gastric mechanoreceptors.

Motilin, whose release is the trigger for gastric Phase 3, has been identified as the main determinant of the return of hunger after a meal. Furthermore, the release of several peptide hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), cholecystokinin, as well as motilin and ghrelin, contribute to gut-brain signaling with relevance to the control of hunger and satiety.

Various nutrients, such as bitter tastes, as well as pharmacological agents, such as endocannabinoid receptor antagonists and GLP-1 analogues, act on these pathways to influence hunger, satiety, and food intake.

Conclusion

Gastrointestinal mechanisms such as gastric accommodation and motilin release are key determinants of satiety and hunger.