Acute pancreatitis (AP) is responsible for nearly 300,000 admissions annually in the US [1], and results in locoregional inflammation that can extend to a systemic inflammatory response. Among all patients with AP, 15% to 20% will develop severe acute pancreatitis, with variable necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma and retroperitoneal peripancreatic soft tissue [2-4].

Necrotizing pancreatitis (PN), and the associated systemic inflammatory insult, is commonly complicated by multisystem organ failure, infection, and significant morbidity [5,6].

Such complications often result in a prolonged hospital stay and the frequent need for intervention and readmission [5]. Current mortality rates in NP remain at 15% to 20% [3,6-8].

The disease course of PN is frequently perceived as two discrete phases that correlate with peaks in mortality: an early phase and a late phase[9].

The early phase extends from the onset of PN to 1 to 2 weeks into the disease course, and mortality is secondary to multiple organ failure, resulting from the inflammatory insult induced by pancreatic inflammation [9].

The late phase, from approximately 2 weeks onwards, is characterized by several months of long recovery, evolution of local complications, development of systemic complications, and infection [5,9,10].

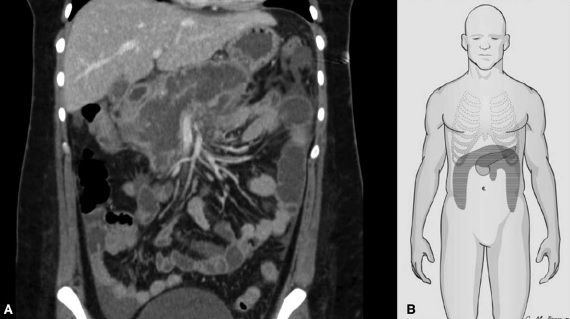

Pancreatic necrosis affects neighboring structures, including the peripancreatic soft tissue, colon, and mesocolon (Fig. 1A) [11]. Involvement of the mesocolon can compromise colonic blood flow, leading to ischemia and complications of ischemia, such as frank necrosis, perforation, and/or ischemic stenosis.

Direct extension of pancreatic necrosis into the nearby colon (Fig. 1B) may result in fistula or stricture formation. The frequent requirement for antibiotic therapy makes patients with NP susceptible to developing Clostridium difficile colitis [12].

The evolution of intervention in NP has seen an increase in percutaneous placement of drains [8,13-15], which can alter the local inflammatory environment surrounding the colon, or even directly injure the colon.

Colonic complications associated with PN, including ischemia, perforation, stenosis, fistula, and C. difficile colitis , often require surgical management for treatment. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are imperative for optimal results.

Figure 1: Cross-sectional image demonstrating how pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis surround neighboring intra-abdominal structures (A). Peripancreatic necrosis may extend downward, either through the parietocolic leak or through the root of the mesentery of the small intestine (B).

In their pancreatitis practice, the authors of this study have observed a significant incidence of colonic involvement in patients with NP. However, the available literature related to colonic involvement in NP is limited to a few low-volume case reports or series [16-18], and very little is known about specific risk factors.

Therefore, they sought to determine the incidence of colonic involvement in a large series of patients and quantify its impact on outcomes. Additionally, we sought to determine potential risk factors for the development of colonic involvement in patients with NP.

It was hypothesized that patients with colonic involvement requiring surgical intervention, in the setting of necrotizing pancreatitis, could have worse clinical outcomes than those patients with NP without colonic involvement.

| Methods |

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for a retrospective review of the institutional PN database to identify all patients who developed a colonic complication during PN. This database includes all NP patients treated at Indiana University Health University Hospital (IU-UH) between 2005 and 2017.

All patients with NP are included, regardless of age, etiology, or treatment strategy. The 2017 cut-off point was chosen to ensure capture of all long-term complications, such as colonic stenosis.

Acute pancreatitis and severe acute pancreatitis were defined according to the revised Atlanta classification [9]. Necrosis was defined as a lack of enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma and/or findings of peripancreatic necrosis, such as an acute necrotic collection, or a walled-off necrosis on contrast-enhanced cross-sectional images [9].

The development of colonic complications in all patients with PN was evaluated by retrospective manual review, and was defined based on the clinical observations of the treating physicians, recorded in the clinical notes, diagnostic reports, and description of the findings by the the surgeons at the time of the operation, reported in the operating protocols. These complications included ischemia, perforation, fistula, stenosis/obstruction, and C. difficile colitis .

Perforation was defined as a violation of the full thickness of the colonic wall confined to the abdominal cavity, or controlled by a previously placed percutaneous drain. Colocutaneous fistula was defined as a violation of the full thickness of the colonic wall with direct communication through the integument. Additionally, operative notes were consulted to characterize the type of initial procedure, the type of procedure at reoperation, and the location of colonic involvement.

Demographic variables of interest were recorded prospectively and included age, sex, comorbidities, and etiology of pancreatitis. Clinical variables of interest included organ failure, pancreatic duct disconnection syndrome, infected pancreatic necrosis, duration of PN, readmission, morbidity, and mortality.

Organ failure was defined according to the modified Marshall scoring system of organ dysfunction [9,19].

Pancreatic duct disconnection syndrome was suggested radiographically, and confirmed clinically [20,21]. Major morbidity was defined as a complication of grade III or higher of the Clavien-Dindo classification [22].

The evolution of the pancreatic necrosis treatment strategy at the authors’ institution has been described in detail in a separate report [8]; However, several changes have occurred during the study period that deserve mention. Maximum medical support and early enteral nutrition were used in all PN patients, avoiding total parenteral nutrition whenever possible.

Between 2005 and 2006, prophylactic antibiotics were used, and that practice was abandoned from 2007 onwards. Historically, the management of pancreatic necrosis was primarily surgical. Beginning in 2008, the approach to pancreatic necrosis evolved to more widely apply minimally invasive techniques as the first step in intervention for necrosis.

The current treatment strategy at IU-UH reflects the evidence-based guidelines published in 2013 by the International Association of Pancreatology, and the American Pancreatic Association .

Clinical characteristics were evaluated to identify risk factors, and results were reviewed to determine the impact of colonic involvement on morbidity and mortality. Descriptive statistics were applied to describe the cohort of patients with colonic complications, including number (with percentage), mean (with standard error of the mean [SEM]), and median (with range).

To determine differences between groups, categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using the independent samples t test. To identify independent risk factors for colonic involvement in NP, variables identified in the univariate analysis with P < 0.20 were included in a binary logistic regression analysis.

To evaluate the independent impact of colonic involvement on NP, binary logistic regression and linear multiple regression analyzes were used for categorical and continuous outcomes, respectively.

Odds ratios (OR) were reported with 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate. Values of P < 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. The data were recorded using the Microsoft Excel 2018 program (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA) and analyzed with the IBM SPSS 25.0 program (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

| Results |

> Incidence, type and timing of the complication

The incidence of surgical intervention due to colonic involvement in PN was 11% (69/647). Colonic complications included: ischemia (n = 29), perforation (n = 18), fistula (n = 12), inflammatory stricture (n = 7), and fulminant C. difficile colitis (n = 3).

The median time from the start of PN to surgical intervention for colonic complications was 44 days (range: 8-466).

Ischemia, perforation, and fulminant colitis due to C. difficile occurred early in the disease curve, while fistula and inflammatory stenosis developed in a delayed manner.

• Ischemia

Colonic ischemia complicated PN in 29 patients. The majority (n = 18) were male. The most common etiology was biliary (n = 20) and alcoholic (n = 6). Ischemia involved both the right and left colon in 14 patients, the right colon only in 10, and the left colon only in 5 patients.

Organ failure prior to the development of colonic ischemia was seen in 21 patients. Respiratory failure developed in 21 patients, renal failure in 14 patients, and cardiovascular failure in 11 patients. Multiorgan systemic failure was seen in 17 patients who developed colonic ischemia. In 10 patients, worsening cardiovascular failure was the dominant clinical presentation of colonic ischemia.

In patients who developed colonic ischemia, mesenteric vein thrombosis was diagnosed in 17 (59%). The incidence of mesenteric vein thrombosis was significantly higher in patients with colonic ischemia compared with patients without (244/618; 39%; P = 0.04). Thrombosis of the mesenteric vein developed on a mean of 14.5 days (SEM: 14.8), before the development of colonic ischemia.

In 14 of 17 patients, the diagnosis of mesenteric vein thrombosis preceded ischemia. In the remaining 3 patients, cross-sectional imaging was performed without contrast enhancement in the setting of acute kidney injury; In all of these cases, mesenteric vein thrombosis was diagnosed on the first transverse section image, after surgery for colonic ischemia.

• Drilling

In 18 patients who experienced colonic perforation, 9 (50%) had a drain previously placed percutaneously. Management of preperforation necrosis included percutaneous drainage only (n = 7), pancreatic debridement only (n = 6), and both (n = 2).

Only 3 patients did not undergo intervention for necrosis before colonic perforation. None of the patients who developed colonic perforation were definitively managed nonoperatively or with minimally invasive approaches; all patients eventually underwent surgical intervention.

• Fistula

Colocutaneous fistula developed in 12 patients. One patient developed a spontaneous colonic fistula without prior intervention for necrosis; the remaining 11 patients underwent surgery for necrosis before fistula development.

Five patients underwent percutaneous drainage followed by open pancreatic debridement, and 3 patients underwent percutaneous drainage alone. The other 3 treatments were open pancreatic debridements followed by percutaneous drainage (n = 1), percutaneous drainage and then video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (n = 1), and open pancreatic debridement alone (n = 1).

None of the patients who developed a colocutaneous fistula were definitively managed non-operatively, or with minimally invasive approaches: all patients eventually underwent surgical intervention.

• Inflammatory stenosis

Inflammatory stenosis (Fig. 2) was diagnosed in 7 patients. In treatment it was operative in all of them. The left colon was involved in 4 patients, and the right colon in 3 patients. Five patients developed colonic obstruction requiring colectomy and concomitant open pancreatic debridement.

Inflammatory stricture developed after percutaneous drain placement in 1 patient, and after open pancreatic debridement in 1 patient. In all cases, preoperative imaging demonstrated peripancreatic necrosis surrounding the involved colonic segment.

Figure 2: Barium enema demonstrating an 11 cm inflammatory stricture in the descending colon (arrow), in a patient with necrotizing pancreatitis

• Clostridium difficile colitis

Of the 647 patients examined with PN, a total of 65 (10%) were diagnosed with a C. difficile infection (CDI) during the course of their disease. Three patients underwent surgery for fulminant C. difficile colitis and 2 died secondary to fulminant C. difficile colitis after total abdominal colectomy.

In the 62 patients who did not require surgical intervention for CDI, 5 died before resolution of PN, and these deaths were not attributable to CDI. The medical treatment of CDI required a mean of 12.8 days (SEM: 0.6) of antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic treatment was generally oral with metronidazole (n = 30); other regimens included oral metronidazole and oral vancomycin (n = 17), intravenous metronidazole and oral vancomycin (n = 10), oral vancomycin only (n = 4), or intravenous metronidazole only (n = 4). An in-depth analysis of CDI in PN was the focus of a discrete analysis that has been previously published [12].

> Percutaneous drainage

During the course of PN, 216 patients (33%) underwent percutaneous drainage (PD) as the first step, or as the definitive management of pancreatic necrosis. Thirty-six (17%) of those 216 patients who underwent PD placement subsequently developed a colonic complication.

In comparison, 33 of 431 patients (8%), who did not undergo PD placement, developed a colonic complication. The increased rate of colonic complications in NP patients undergoing PD placement was statistically significant ( P = 0.0007).

PN patients undergoing PD placement had a 2.4-fold increased risk of developing a colonic complication (OR 2.4; 95% CI: 1.5-4.0; P = 0.0007). Radiographic or operative evidence that PD caused direct injury to the colon was evident in 3 patients.

> Location and management

Among all colonic pathology, the right colon was involved in 27 patients (39%), and the left colon in 23 (33%). The entire colon was involved in 18 patients (26%). One patient (1%) had isolated involvement of the sigmoid colon.

The initial surgical management of colonic pathology is shown in Figure 3. Six patients underwent additional colonic resection during reoperation.

Colonic intervention was concomitant with pancreatic debridement in 39 patients (57%), and after initial pancreatic debridement in 25 patients (36%).

Five patients (7%) did not require pancreatic debridement; In them, the intervention for necrosis included PD only (n = 3), and medical treatment only (n = 2).

Those NP patients with colonic involvement required a mean of 5.6 (SEM: 0.5) procedures, compared with 2.3 (SEM: 0.1) procedures in patients without colonic involvement ( P < 0.0001). .

The time from the beginning of PN to the first intervention for necrosis, in patients with colonic involvement, had a mean of 35.7 days (SEM: 3.8), and was significantly shorter than in patients without colonic involvement. (94.3 days; SEM: 5.6: P = 0.001).

Forty-eight patients (70%) underwent a diverting ostomy. The ostomy was reversed in 27 patients (56%); 13 patients did not undergo reversal during the follow-up period, and 1 patient underwent a multivisceral transplant. Ostomy reversal was performed a mean of 248.1 days (SEM: 30.2) after the initial colonic operation.

> Risk factors

Independent risk factors associated with colonic involvement in NP, in the multivariate analysis included: smoking (OR 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2-3.4; P = 0.009), coronary artery disease (OR 1 .9; 95% CI: 1.1-3.7; P = 0.04), and respiratory failure (OR 4.7; 95% CI: 1.1-26.3; P = 0.049).

NP patients referred to the IU-UH were 2.3 times more likely to develop colonic complications (95% CI: 1.1-5.0; P 0.04), when compared with patients admitted directly.

Respiratory and renal failure were almost 2 times more common in patients with colonic involvement, when compared to those without involvement. Cardiovascular failure was 3 times more common in patients with colon involvement, when compared to those without involvement.

Colonic complications developed at a mean of 56.3 days (SEM: 9.3) after the onset of initial organ failure.

Respiratory, renal, and cardiovascular failure preceded colonic involvement by a mean of 57.7 days (SEM: 5.9), 49.1 days (SEM: 4.8), and 41.9 days (SEM: 12). ,9), respectively. At the time of diagnosis of colonic pathology, organ failure was present in 27 patients (39%), and included respiratory failure in 25 (36%), renal failure in 16 (23%), and cardiovascular failure in 12 (17%). ) patients.

> Infected necrosis

Infection necrosis developed in 80% of patients with colonic involvement (n = 55). Infected necrosis was diagnosed at a mean of 30.8 days (SEM: 6.8) before diagnosis of colonic involvement. Infected necrosis was diagnosed > 24 hours before colonic involvement in 30 patients (55%), within 24 hours in 22 patients (40%), and after colonic involvement in only 3 patients (5%).

> Morbidity

NP patients with colonic involvement had significantly increased morbidity when compared to those without colonic involvement. They had increased rates of infected necrosis, readmission, and organ failure, longer length of hospital stay, greater number of procedures, more frequent readmissions, increased major morbidity, and longer duration of illness.

In multivariable analysis, colonic involvement in PN was independently associated with increased rates of infected necrosis and readmission, and greater number of procedures, readmissions, length of stay, and duration of illness.

> Mortality

Overall mortality in patients with NP with colonic involvement was 19% (13 of 69) and was significantly increased when compared with patients with NP without colonic involvement (44 of 578 patients, 8%; P = 0.002). .

In the multivariate analysis, colonic involvement in PN was not an independent risk factor for mortality ( P = 0.29). Mortality was observed in 9 patients with ischemic colitis (9/29, 31%), 2 patients with colonic perforation (2/18, 11%), and 2 patients with fulminant colitis due to C. difficile (2/3, 67%). .

No mortality was observed in patients with fistula or inflammatory stricture of the colon. Causes of mortality in NP patients with colonic involvement included systemic multiorgan failure attributable to colon pathology (n = 6), systemic multiorgan failure attributable to infected pancreatic necrosis (n = 4), cardiopulmonary event after discharge (n = 2), and progressive physiological atrophy with hospital care (n = 1).

| Discussion |

Few studies in the pancreatic literature have evaluated colonic complications in NP, and to date, no large series has evaluated the incidence, type, and outcomes of these colonic complications. The major finding of this large observational series is that the incidence of colonic involvement in PN is substantial (11%).

Risk factors for colonic pathology include a history of smoking and coronary artery disease; those patients who developed respiratory failure had the highest risk for colonic involvement in PN.

Colonic involvement was eventually distributed among the right, left, and entire colon, and most commonly consisted of ischemia or perforation. Surgical management of colonic complications in NP resulted in increased morbidity (96%) and mortality (19%).

Colonic pathology originating in PN has been previously reported in small volume series. Nagpal et al. [16], retrospectively reviewed 8 patients who required colectomy for colonic involvement in the PN.

All of these operations were performed for ischemia and subsequent perforation, and only 1 patient in that cohort died. Van Minnen et al. [17], reported 14 patients who underwent colectomy for open perforation, resulting in a mortality rate of 78%. The largest study to date, reported by Meyer et al. [18], in 1990, examined 159 patients with PN over a 2-year period.

In this population, the incidence of colonic involvement in PN was 6.3%, and only 1 patient survived. None of these small case series were able to provide details such as timing or risk factors for colonic complications in PN.

Data from the present study suggest that colonic involvement in PN may be substantially more prevalent (11%) than previously thought. Colon pathology should be a clinical consideration in patients with NP, particularly in those with clinical deterioration.

The timing of colonic complications was variable and depended on the type of colonic involvement in PN. For example, fulminant C. difficile colitis , ischemia, and perforation occur early after the onset of PN, typically within the first month.

The more indolent pathology, such as inflammatory stenosis or fistula, occurs in a delayed manner, several months into the pathological process. Most patients currently undergo colectomy, fecal diversion, and pancreatic debridement. However, it is worth mentioning a subgroup of patients who fail to improve clinically after attempting minimally invasive management of pancreatic necrosis with percutaneous drainage.

In many of these patients, colonic involvement was identified at the time of “step-up” pancreatic debridement, and likely contributed to the stalled clinical improvement.

This retrospective view prevents the identification of PD as a risk factor for colonic complications in NP; However, minimally invasive interventions for necrosis are not without risk. In the PANTER trial, 14% of PN patients in the intensification arm underwent additional intervention for enterocutaneous fistula or perforation [13].

As the field moves toward more minimally invasive management of pancreatic necrosis, colonic complications may be more difficult to identify, since they are not always easily evaluated on cross-sectional images. Improved knowledge of the risk factors and timing of colonic complications related to the initiation of PN may assist the clinician by increasing clinical suspicion and guiding diagnostic evaluation.

Several important risk factors for the development of colonic involvement in PN were identified . A history of tobacco use or coronary artery disease and the development of respiratory failure were most strongly associated with colonic complications. Tobacco use results in significant microvascular changes [23], and coronary artery disease is associated with vascular disease elsewhere [24].

Such information could suggest that colonic complications are related to mesenteric blood flow during PN, which may be further disrupted by systemic inflammation and organ failure.

Interestingly, with that information one could predict that the dividing areas of the colon will be more commonly affected.

However, colonic ischemia was distributed throughout the entire colon; therefore, ischemic colopathies likely have a more complex pathogenesis than the simple low-flow state.

Other contributing factors likely include a profound inflammatory response associated with PN, prior interventions, mesenteric venous thrombosis, and specific patterns of necrosis. An interesting finding is that the incidence of mesenteric vein thrombosis was higher in patients who developed colonic ischemia.

The small number of patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis and colonic ischemia in this study precludes the possibility of recommending changes to the current treatment strategy for mesenteric vein thrombosis in NP, and the decision to anticoagulate should be made on the basis of case by case basis.

The results of this study document a much higher morbidity in those patients with colon involvement in PN, and were associated with double the incidence of organ failure, longer time to resolution, more frequent hospital readmissions, greater number of procedures, and longer duration of illness.

This observation leads to the question of whether the increased morbidity seen in PN patients with colonic involvement is attributable to the colonic complication, or whether patients with more severe PN develop a colonic complication.

Both statements are probably true. The 19% mortality rate in NP patients who developed colonic complications is more than twice that of patients without colonic involvement, and highlights the critical need for early diagnosis and treatment.

The management of colon pathology in PN is complex and depends on each patient and the type of colonic involvement. Ischemia, fulminant C. difficile infection , and perforation with peritonitis demand urgent/emergent surgical intervention. Any doubt about intestinal viability justifies a planned “ second look” operation.

The management of colonic fistula requires mature clinical judgment to determine the timing and type of intervention.

Similar to perforated diverticulitis or enterocutaneous fistula due to other pathologies [25-28], hemodynamically stable NP patients, in the absence of diffuse peritonitis and sepsis, can be initially treated with antibiotics and/or PD.

However, an important difference in patients with NP included in clinical practice and highlighted in this series is that definitive treatment of colonic perforation or fistula is not possible with minimally invasive approaches alone. That is most likely due to a combination of factors, including locoregional and systemic inflammation, poor nutritional status, altered perfusion, and the need for debridement for pancreatic necrosis, as co-factors in the treatment algorithm.

Colonic stricture may require diversion prior to definitive resection. Longitudinal evaluation of the patient’s clinical status will help determine the best “window” for surgery, and should consider nutritional optimization, physical rehabilitation, and timing of intervention in relation to management of necrosis.

It would be ideal to evaluate the relationship between colonic involvement in NP and the use of antibiotics or prophylactic anticoagulation. Given the heterogeneous nature of PN, the prolonged course of the disease, multiple hospital admissions, and the frequent requirement for admission to a subacute institution, evaluation of the type and timing of antibiotics and prophylactic anticoagulation proved to be impractical. retrospectively.

Infectious complications develop frequently, often many times throughout the course of the disease, and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during the course of PN is highly dependent on multiple factors specific to each patient (renal function, hemorrhagic complications, surgical intervention). , medical service and acuity, discharge disposition, etc.).

That amount of variation among research subjects prohibits any meaningful statistical analysis of the impact of antibiotic use or prophylactic anticoagulation on colonic complications. The timing of colon involvement in NP in relation to identified risk factors and outcomes is difficult to pinpoint exactly.

Clinical records, radiographic reports, and surgical protocols were used to identify patients with colonic pathology in PN; therefore, patients who developed colonic pathology but were asymptomatic may not have been captured.

Additionally, patients with rapid clinical deterioration and death, in whom surgical intervention was not performed, may have had an undiagnosed colonic complication, such as ischemic colitis, fulminant C. difficile colitis , or perforation.

Barium enema was only performed in patients with symptoms related to colonic stenosis, and it is possible that those with minimally symptomatic stenosis were not identified in this study. The greatest strength of this study is the size of the patient population and the ability to estimate incidence and provide potential risk factors.

Conclusion Clinicians should be aware that colonic involvement in necrotizing pancreatitis is more common than current literature suggests, and should suspect it in patients with clinical deterioration. With high suspicion, these complications can be diagnosed and treated early, and this can improve the significant morbidity and mortality associated with colonic involvement in NPs. |