Unvaccinated people threaten the safety of vaccinated people even when SARS-Cov-2 vaccination rates are high, according to a new modeling study published in CMAJ ( Canadian Medical Association Journal ).

Background:

The speed of vaccine development has been a singular achievement during the COVID-19 pandemic, although acceptance has not been universal. Vaccine opponents often frame their opposition in terms of the rights of the unvaccinated. We sought to explore the impact of mixing vaccinated and unvaccinated populations on the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among vaccinated individuals.

Methods:

We built a simple susceptible-infectious-recovered compartmental model of a respiratory infectious disease with 2 connected subpopulations: vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

We simulated a spectrum of mixing patterns between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups ranging from random mixing to complete mixing of equals (complete asortativity), in which people have contact exclusively with others with the same vaccination status. We evaluate the dynamics of an epidemic within each subgroup and in the population as a whole.

Results:

We found that the risk of infection was notably higher among unvaccinated people than among vaccinated people under all mixing assumptions.

The contact-adjusted contribution of unvaccinated people to the risk of infection was disproportionate, with unvaccinated people contributing to infections among those who were vaccinated at a higher rate than would have been expected based on contact numbers alone.

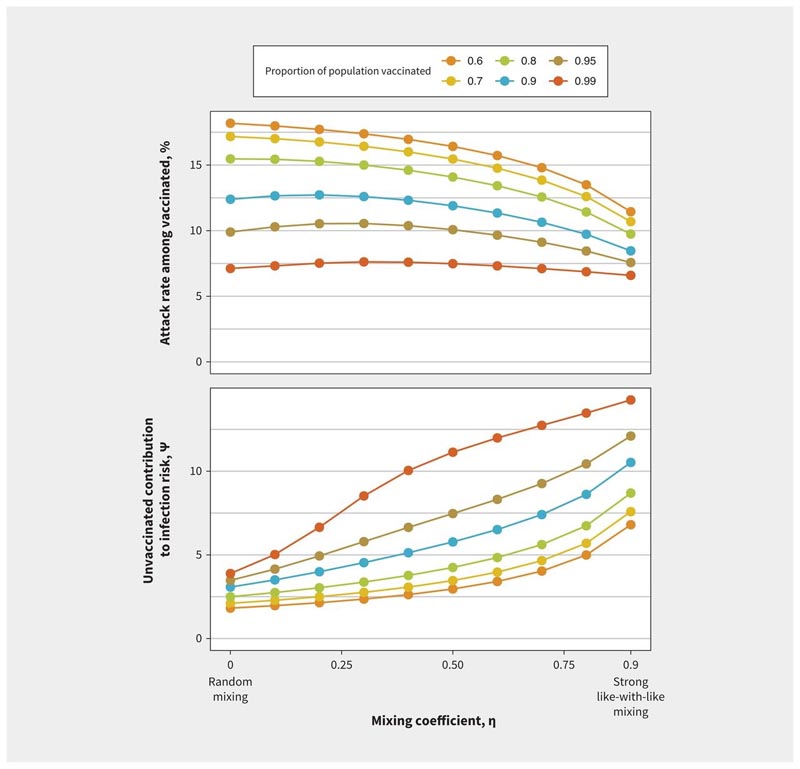

We found that as the mixing of similar people increased, attack rates among vaccinated people decreased from 15% to 10% (and increased from 62% to 79% among unvaccinated people), but the adjusted risk contribution Contact between vaccinated people derived from contact with unvaccinated people increased.

Impact of mixing between vaccinated and unvaccinated subpopulations on the contribution to the risk and final size of the epidemic with increasing population vaccination coverage. Increasing population vaccination coverage decreases the attack rate among vaccinated individuals and further increases the relative contribution to risk in vaccinated individuals by unvaccinated individuals at any similar mixing level. For the levels of vaccination coverage that were evaluated, increasing similar mixing reduces the attack rate among the vaccinated but increases the relative contribution to risk in vaccinated individuals by the unvaccinated.

Interpretation: Although the risk associated with avoiding vaccination during a virulent pandemic falls primarily on people who are not vaccinated, their choices affect the risk of viral infection among those who are vaccinated in a way that is disproportionate to the share of unvaccinated people in the population. |

Comments

"Many opponents of vaccine mandates have framed vaccine uptake as a matter of individual choice," writes Dr. David Fisman, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, with co-authors. "However, we found that the decisions made by people who forgo vaccination contribute disproportionately to the risk among those who do get vaccinated."

The researchers used a simple model to explore the effect of mixing vaccinated and unvaccinated people to understand the dynamics of an infectious disease like SARS-CoV-2. They simulated mixing of similar populations in which people have exclusive contact with others of the same vaccination status, as well as random mixing between different groups. When the unvaccinated were mixed with the unvaccinated, the risk to vaccinated people was lower. When vaccinated and unvaccinated people mix, a substantial number of new infections occur in vaccinated people, even in settings where vaccination rates are high.

The authors’ findings remained stable even when they modeled lower levels of vaccine effectiveness in preventing infection, such as in those who did not receive a booster dose or with new variants of SARS-CoV-2. These findings may be relevant to future waves of SARS-CoV-2 or to the behavior of new variants.

"The risk among unvaccinated people cannot be considered selfish," the authors write. In other words, giving up vaccination cannot be considered to affect only the unvaccinated, but also those around them. "Considerations of equity and fairness for people who choose to be vaccinated, as well as for those who choose not to be vaccinated, should be taken into account in the formulation of vaccination policy," the authors conclude.