Monkeypox is a rare disease caused by infection with the monkeypox virus. Monkeypox virus belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus of the family Poxviridae. The genus Orthopoxvirus also includes variola virus (which causes smallpox), vaccinia virus (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox virus.

Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 when two outbreaks of a smallpox-like disease occurred in colonies of monkeys kept for research, hence the name "monkeypox." The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) during a period of intensified efforts to eliminate smallpox. Since then, monkeypox has been reported in people from several other countries in central and west Africa: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Liberia, Nigeria, Republic of the Congo, and Sierra Leone. Most infections occur in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Cases of monkeypox in people have occurred outside of Africa related to international travel or imported animals, including cases in the United States, as well as Israel, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

The natural reservoir of monkeypox remains unknown. However, African rodents and non-human primates (such as monkeys) can harbor the virus and infect people.

| Signs and symptoms |

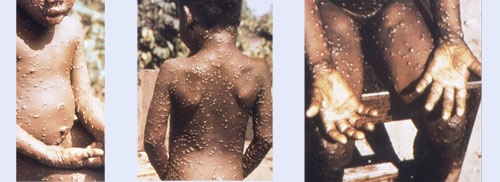

In humans, the symptoms of monkeypox are similar but milder than the symptoms of smallpox. Monkeypox begins with fever, headache, muscle aches, and exhaustion . The main difference between the symptoms of smallpox and monkeypox is that monkeypox causes the lymph nodes to swell (lymphadenopathy) while smallpox does not. The incubation period (time from infection to symptoms) for monkeypox is usually 7 to 14 days, but can range from 5 to 21 days.

> The disease begins with:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle pains

- Back pain

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Shaking chills

- Exhaustion

Within 1 to 3 days (sometimes longer) after the onset of fever, the patient develops a rash that often begins on the face and then spreads to other parts of the body.

> Injuries progress through the following stages before falling:

- Spots

- Papules

- Vesicles

- Pustules

- Scabs

The illness usually lasts 2 to 4 weeks.

In Africa, monkeypox has been shown to cause death in up to 1 in 10 people who contract the disease.

| Information for doctors |

Early symptoms of monkeypox include fever, malaise, headache, and sometimes a sore throat and cough. A hallmark of monkeypox is lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes). This usually occurs with the onset of fever, 1 to 2 days before the onset of the rash, or rarely with the onset of the rash. Lymph nodes can swell in the neck (submandibular and cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal) and occur on both sides of the body or just one.

| Clinical recognition |

You can recognize possible monkeypox infection based on the similarity of its clinical course with that of ordinary smallpox.

After infection, there is an incubation period that lasts on average 7 to 14 days. The development of initial symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise, headache, weakness, etc.) marks the beginning of the prodromal period.

A feature that distinguishes monkeypox infection from smallpox is the development of swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy).

Lymph node swelling can be generalized (involving many different locations in the body) or localized to several areas (for example, neck and armpit).

Shortly after the prodrome, a rash appears. The lesions usually begin to develop simultaneously and evolve together anywhere on the body. The evolution of the lesions progresses through four stages: macular, papular, vesicular, to pustular, before crusting and resolution.

This process occurs over a period of 2-3 weeks. The severity of the disease may depend on the initial health of the individual, the route of exposure, and the strain of the infectious virus (West African vs. Central African genetic groups or clades of viruses). West African monkeypox is associated with milder illness, fewer deaths, and limited human-to-human transmission. Human infections with the Central African monkeypox virus clade are typically more severe compared to those with the West African virus clade and have higher mortality. Human-to-human spread is well documented for Central African monkeypox virus.

| Monkeypox disease |

> Incubation period

- Monkeypox virus infection begins with an incubation period. A person is not contagious during this period.

- The incubation period averages 7-14 days, but can vary from 5-21 days.

- A person has no symptoms and may feel fine.

> Prodrome

- People with monkeypox will develop an early set of symptoms (prodrome). A person can sometimes be contagious during this period.

- Early symptoms include fever, malaise, headache, sometimes sore throat and cough, and lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes).

- Lymphadenopathy is a hallmark feature of smallpox monkeypox.

- This usually occurs with the onset of fever, 1-2 days before the onset of the rash, or rarely with the onset of the rash.

- Lymph nodes can swell in the neck (submandibular and cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal) and occur on both sides of the body or just one.

> Skin lesions

After the prodrome, lesions will develop in the mouth and body. Injuries progress through several stages before falling. A person is contagious from the onset of the enanthem through the scab stage.

| Editor’s note : A new article in The Lancet Infectious Disease states that: " Prolonged shedding of viral DNA from the upper respiratory tract after resolution of skin lesion challenged current infection prevention and control guidance." (See below) |

Monkeypox lesions usually scab over and heal on their own in two to four weeks. (UK Health Security Agency )

| Stages from enanthem through scab stage |

Enanthem The first lesions that develop are on the tongue and in the mouth. Spots 1−2 days After the enanthem, a macular rash appears on the skin, starting on the face and spreading to the arms and legs and then to the hands and feet, including the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. The rash usually spreads to all parts of the body within 24 hours and is most concentrated on the face, arms, and legs (centrifugal distribution). Papules 1−2 days By the third day of the eruption, the lesions have progressed from macular (flat) to papular (raised). Vesicles 1−2 days By the fourth to fifth day, the lesions have become vesicular (raised and filled with clear fluid). Pustules 5–7 days By the sixth to seventh day, the lesions have become pustular (filled with opaque fluid): sharply raised, usually round, and firm to the touch (deep-seated). The lesions will develop a depression in the center (umbilication). The pustules will remain for approximately 5 to 7 days before beginning to scab over. Scabs 7−14 days By the end of the second week, the pustules have formed scabs and scabs. The scabs will remain for about a week before beginning to fall off. Eruption resolved Scars and/or areas of lighter or darker skin may remain after the scabs have fallen off. Once all the scabs have fallen off, a person is no longer contagious. |

| Preparation and collection of specimens |

Effective communication and precautionary measures between specimen collection teams and laboratory personnel are essential to maximize safety in handling monkeypox specimens.

This is especially relevant in hospital settings, where laboratories routinely process samples from patients with a variety of infectious and/or non-infectious conditions.

A labeling system must clearly distinguish all samples, including those from monkeypox patients who require special handling.

Laboratory exposures to poxviruses occur primarily through needlestick injuries, direct contact with the specimen, or aerosols that can be generated by laboratory procedures . Sharps should not be included with any specimen and should be disposed of in appropriate puncture-resistant containers for autoclaving infectious waste.

Specimen collection can begin after appropriate consultations have been made. The procedures and materials used will vary depending on the phase of the eruption.

| Collection of specimens for the diagnosis of monkeypox |

Possible human cases of monkeypox should be reported to your local hospital epidemiologist and/or infection control staff, who will contact your state health department.

Personnel collecting samples should wear personal protective equipment (PPE) in accordance with recommendations for standard, contact, and droplet precautions. Specimens should be collected in the manner described below. When possible, use plastic materials instead of glass for sample collection.

Real-time PCR can be used on lesion material to diagnose possible infection with monkeypox virus.

Consultation with the state health department and CDC should occur prior to collecting samples.

A sample should be taken from more than one lesion, preferably from different locations on the body and/or from lesions with different appearances. See Poxvirus Molecular Detection and Poxvirus Serology Tests in the CDC Testing Directory for specimen storage, packaging, and shipping instructions.

| Treatment |

At this time, there are no specific treatments available for monkeypox infection, but monkeypox outbreaks can be controlled.

Smallpox vaccine, cidofovir, ST-246, and vaccinia immunoglobulin (VIG) can be used to control a monkeypox outbreak. CDC guidance was developed using the best available information on the benefits and risks of smallpox vaccination and drug use for the prevention and management of monkeypox and other orthopoxvirus infections.

> Vaccine against monkeypox and smallpox

A vaccine, JYNNEOSTM (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex), has been licensed in the United States to prevent monkeypox and smallpox. Because the monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can also protect people from contracting monkeypox. Previous data from Africa suggest that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. The efficacy of JYNNEOSTM against monkeypox was concluded from a clinical study on the immunogenicity of JYNNEOS and efficacy data from animal studies. Experts also believe that vaccination after exposure to monkeypox can help prevent the disease or make it less severe.

ACAM2000, which contains a live vaccinia virus, is licensed for immunization in people who are at least 18 years of age and at high risk for smallpox infection. It can be used in people exposed to monkeypox if used under an expanded access investigational new drug protocol.

The smallpox vaccine is not currently available to the general public. In the event of another monkeypox outbreak in the United States, the CDC will establish guidelines explaining who should get vaccinated.

> Monkeypox and Smallpox Vaccine Guide

When administered appropriately before exposure to monkeypox, vaccines are effective in protecting people against monkeypox.

ACAM200 and JYNNEOSTM (also known as Imvamune or Imvanex) are the two vaccines currently authorized in the United States to prevent smallpox. JYNNEOS is also specifically licensed to prevent monkeypox.

ACAM2000 is administered as a live virus preparation that is inoculated into the skin by pricking the surface of the skin. After successful inoculation, a lesion will develop at the vaccination site. The virus that grows at the site of this inoculation lesion can spread to other parts of the body or even to other people. People who receive the vaccine with ACAM2000 should take precautions to prevent the spread of the vaccine virus.

JYNNEOSTM is administered as a live virus that does not replicate. It is administered as two subcutaneous injections four weeks apart. There is no visible "shot" and, as a result, there is no risk of spread to other parts of the body or other people. People who receive JYNNEOS TM are not considered vaccinated until they receive both doses of the vaccine.

CDC, in conjunction with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), provides recommendations on who should receive smallpox vaccine in a non-emergency setting. At this time, ACAM2000 vaccination is recommended for laboratories working with certain orthopoxviruses and military personnel. ACIP is currently evaluating JYNNEOSTM for the protection of persons at risk of occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses in a pre-event setting.

> Vaccine effectiveness

Because the monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect people from contracting monkeypox. Previous data from Africa suggest that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. The efficacy of JYNNEOSTM against monkeypox was concluded from a clinical study on the immunogenicity of JYNNEOS and efficacy data from animal studies.

Smallpox and monkeypox vaccines are effective in protecting people against monkeypox when given before exposure to monkeypox. Experts also believe that vaccination after exposure to monkeypox can help prevent the disease or make it less severe.

> Receive the vaccine after exposure to monkeypox virus

Vaccination after exposure to monkeypox virus is still possible. However, the sooner an exposed person receives the vaccine, the better.

The CDC recommends that the vaccine be administered within 4 days of the date of exposure to prevent the onset of illness. If given 4 to 14 days after the date of exposure, vaccination may reduce disease symptoms, but may not prevent disease.

Smallpox and monkeypox vaccines are effective in protecting people against monkeypox when given before exposure to monkeypox. Experts also believe that vaccination after exposure to monkeypox can help prevent the disease or make it less severe.

> Revaccination after exposure

People exposed to the monkeypox virus and who have not received the smallpox vaccine in the past 3 years should consider getting vaccinated.

The sooner a person receives the vaccine, the more effective it will be in protecting against the monkeypox virus.

> Risks of the vaccine vs. monkeypox disease

For most people who have been exposed to monkeypox, the risks of monkeypox disease are greater than the risks of the smallpox or monkeypox vaccine.

Monkeypox is a serious disease . It causes fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, swollen lymph nodes, a general feeling of discomfort, exhaustion, and a severe skin rash. Studies of monkeypox in Central Africa, where people live in remote areas and are medically underserved, showed that the disease killed 1-10% of infected people.

In contrast, most people who receive the smallpox or monkeypox vaccine have only minor reactions, such as mild fever, tiredness, swollen glands, and redness and itching at the site where the vaccine is given. However, these vaccines also have more serious risks.

Based on past experience, it is estimated that 1 to 2 people out of every 1 million vaccinated people will die as a result of life-threatening complications from the vaccine.

> Cidofovir and Brincidofovir (CMX001)

There are no data available on the effectiveness of Cidofovir and Brincidofovir in the treatment of human cases of monkeypox. However, both have demonstrated activity against poxviruses in in vitro and animal studies.

It is unknown whether or not a person with severe monkeypox infection will benefit from treatment with either antiviral, although their use may be considered in such cases. Brincidofovir may have an improved safety profile over Cidofovir. No serious renal toxicity or other adverse events have been observed during treatment of cytomegalovirus infections with Brincidofovir compared to treatment with Cidofovir.

> Tecovirimat (ST-246)

There are no data available on the effectiveness of ST-246 in the treatment of human cases of monkeypox.

Studies using a variety of animal species have shown that ST-246 is effective in the treatment of orthopoxvirus-induced disease. Human clinical trials indicated that the drug was safe and tolerable with only minor side effects.

> Vaccinia immunoglobulin (VIG)

There are no data available on the effectiveness of VIG in the treatment of monkeypox complications. The use of VIG is administered under an IND and has no proven benefit in treating smallpox complications. It is unknown whether a person with severe monkeypox infection will benefit from VIG treatment, however its use may be considered in such cases.

VIG may be considered for prophylactic use in an exposed person with severe immunodeficiency in T cell function for whom smallpox vaccination after exposure to monkeypox is contraindicated.

> Duration of isolation procedures

Decisions regarding discontinuation of isolation precautions should be made in consultation with the local or state health department.

For people with monkeypox, isolation precautions, whether in health care facilities or home settings, should be continued until all lesions have resolved and a new layer of skin has formed .

After discontinuation of isolation precautions, affected individuals should avoid close contact with immunocompromised individuals until all scabs are gone.

Immunocompromised people include those whose immune mechanisms are deficient due to:

- Immunological disorders (for example, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection or congenital immunodeficiency syndrome).

- Chronic diseases (for example, diabetes, cancer, emphysema or heart failure).

- Immunosuppressive therapy (such as radiation, cytotoxic chemotherapy, anti-rejection drugs, or steroids).

> Monitoring of people who have been exposed

Contacts of animals or people confirmed to have monkeypox should be monitored for symptoms for 21 days after their last exposure.

Symptoms of concern include:

- Fever ≥ 100.4°F (38°C)

- Shaking chills

- New lymphadenopathy (periauricular, axillary, cervical or inguinal)

- New skin rash

Fever and rash occur in almost all people infected with the monkeypox virus.

Contacts should be instructed to check their temperature twice a day.

If symptoms develop, contacts should self-isolate immediately and contact the health department for further guidance.

- If fever or rash develops, contacts should self-isolate and contact their local or state health department immediately.

- If only chills or lymphadenopathy develop, the contact should remain at their residence and self-isolate for 24 hours.

- During this time, the individual should monitor their temperature for fever; If fever or rash develops, the health department should be contacted immediately.

- If fever or rash does not develop and chills or lymphadenopathy persist, the contact should be evaluated by a physician to determine its possible cause. Doctors can check with their state health departments if monkeypox is suspected.

- Contacts who remain asymptomatic may be allowed to continue with routine daily activities (e.g., going to work, school). Contacts should not donate blood, cells, tissues, breast milk, semen or organs while being monitored for symptoms.

> Monitoring of exposed health professionals

Any healthcare worker who has cared for a patient with monkeypox should be alert to the development of symptoms that could suggest monkeypox infection, especially within the 21-day period after the last date of care, and should notify to infection control, occupational health and the health department for guidance on a medical evaluation.

Health care workers who have unprotected exposures (i.e., do not wear PPE) to monkeypox patients do not need to be excluded from work, but should undergo active monitoring for symptoms, including temperature measurement at at least twice a day for 21 days after exposure. Before reporting to work each day, the healthcare worker should be interviewed regarding evidence of fever or rash.

Health care workers who have cared for or been in direct or indirect contact with monkeypox patients while adhering to recommended infection control precautions may undergo self-monitoring or active monitoring as determined by the health department.

Transmission of monkeypox requires prolonged close interaction with a symptomatic individual. Brief interactions and those performed with appropriate PPE in accordance with standard precautions are not high risk and generally do not warrant PPE.

| Update |

CDC Announcement 24 MAY 22 The US has monkeypox vaccines for the susceptible population They have about a thousand doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine, a live virus but with the ability to suppress viral replication. They also have 100 thousand units of a previous compound. Officials from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that they plan to distribute monkeypox vaccines and medical treatments to close contacts of infected people. The announcement was made after five confirmed and probable cases were reported in the country. In terms of supply, the US has about a thousand doses of the JYNNEOS compound, a vaccine approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox and monkeypox "and is expected to increase that level rapidly in the coming weeks as the company provides us with more doses," explained Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the Division of Pathogens and Pathologies of Serious Consequences. There are also nearly 100 million doses of a previous generation vaccine called ACAM2000. Both use live viruses, but only JYNNEOS suppresses the virus’s ability to replicate , making it the safer option, according to McQuiston. According to the FDA, the JYNNEOS vaccine is indicated for individuals 18 years of age and older who are at high risk for smallpox and monkeypox. Epidemiological situation in the USA There is one confirmed infection in Massachusetts, and four other probable cases of people infected with orthopoxvirus - from the same family to which monkeypox belongs - according to CDC officials stated at a press conference. “All suspected cases are presumed to be monkeypox, and are in the process of confirmation at CDC headquarters,” McQuiston said. One of the cases with orthopoxvirus is in New York, another in Florida and the remaining two in Utah. They are all men. The genetic sequence of the case in Massachusetts matches that of a patient in Portugal and belongs to a strain from West Africa, the less aggressive of the two existing strains of monkeypox. "Right now we hope to maximize the distribution of vaccines to those who we know can benefit from them," McQuiston said, according to the AFP agency . That is, "to people who have had contact with a monkeypox patient, health care workers, their closest contacts, and in particular those who may be at high risk of severe disease." People who are immunocompromised or have particular skin conditions, including eczema, are at high risk, added John Brooks, a medical epidemiologist. Transmission of monkeypox occurs through close and sustained contact with someone who has an active skin rash, or through respiratory droplets from someone with lesions of the disease in their mouth and who is around other people for a considerable time. . The virus can cause skin rashes, with lesions occurring in certain parts of the body, or spread more generally. In some cases, in early stages, a rash may start on the genitals or perianal area. While scientists are concerned that the growing number of cases around the world could potentially indicate a new type of transmission, McQuiston said there is currently no evidence to support that theory. Instead, the rising number of cases could be related to some specific contagion events, such as the recent massive parties in Europe. CDC is also developing treatment guidance to allow deployment of the antivirals tecovirimat and brincidofovir, both licensed for the treatment of smallpox. |

Update

Source: Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK . Hugh Adler, PhD, Susan Gould, Paul Hine, et al. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6

Human monkeypox is a zoonosis caused by monkeypox virus, an orthopoxvirus and close relative of the smallpox virus (smallpox). It was first reported in central Africa in 1970 and has historically affected some of the poorest and most marginalized communities in the world.

The clinical syndrome is characterized by fever, rash, and lymphadenopathy. Complications of monkeypox may include pneumonitis, encephalitis, sight-threatening keratitis, and secondary bacterial infections.

Published mortality rates vary substantially and are vulnerable to case ascertainment bias. Case fatality rates ranging from 1% to 10% have been reported in outbreaks in the Congo Basin, and the virus clade circulating in this region appears to be associated with increased virulence. The West African clade, which is responsible for the recent outbreaks in Nigeria, is associated with a lower overall mortality rate consistently below 3%. To date, most reported deaths have occurred in young children and people with HIV.

Human-to-human transmission of monkeypox is well described, including nosocomial and domestic transmission.

However, chains of human-to-human transmission have historically been less recognized. A pooled estimate from a systematic review suggested a secondary attack rate of approximately 8% (range 0 to 11%) among household contacts who were not vaccinated against smallpox.

Understanding of in vivo viral kinetics and infectivity is poor, and the clinical significance of prolonged viremia and skin peeling remains uncertain.

Background

Cases of human monkeypox are rarely seen outside of western and central Africa. There are few data on viral kinetics or the duration of viral shedding, and there are no licensed treatments.

Two oral medications, brincidofovir and tecovirimat, have been approved for the treatment of smallpox and have demonstrated efficacy against monkeypox in animals.

Our objective was to describe the longitudinal clinical course of monkeypox in a high-income setting, along with viral dynamics and any adverse events related to new antiviral therapies.

Methods

In this retrospective observational study, we report the clinical characteristics, longitudinal virological findings and response to unapproved antivirals in seven monkeypox patients who were diagnosed in the United Kingdom between 2018 and 2021, identified through a retrospective note review. of cases.

This study included all patients who were managed at dedicated high consequence infectious diseases (HCID) centers in Liverpool, London and Newcastle, coordinated through a national HCID network.

Results

We reviewed all cases since the inception of the HCID (air) network between August 15, 2018 and September 10, 2021, identifying seven patients . Of the seven patients, four were men and three were women. Three acquired monkeypox in the UK: one patient was a healthcare worker who acquired the virus nosocomially, and one patient who acquired the virus abroad transmitted it to an adult and a child within their household.

Notable features of the disease included viremia, prolonged detection of monkeypox virus DNA in upper respiratory tract smears, reactive moodiness, and one patient had a deep tissue abscess with PCR-positive monkeypox virus. .

Five patients spent more than 3 weeks (range 22-39 days) in isolation due to prolonged PCR positivity.

Three patients were treated with brincidofovir (200 mg once weekly orally), all of whom developed elevated liver enzymes leading to discontinuation of treatment.

One patient was treated with tecovirimat (600 mg twice daily for 2 weeks orally), experienced no adverse effects, and had a shorter duration of viral shedding and illness (10 days of hospitalization) compared to the other six patients. One patient experienced a mild relapse 6 weeks after hospital discharge.

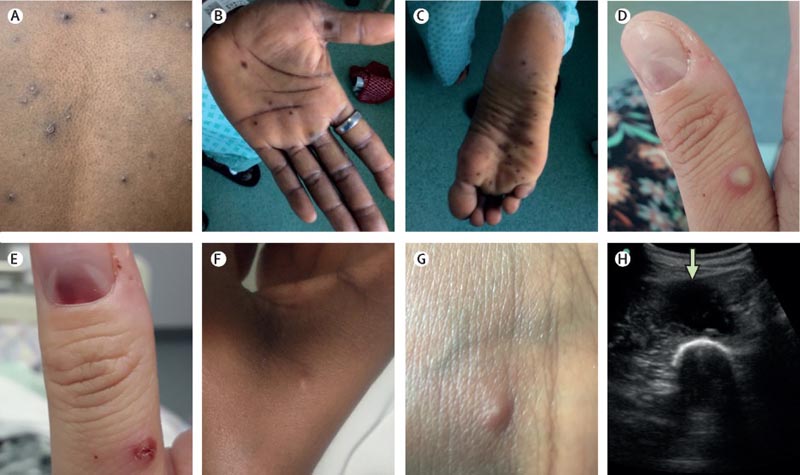

Cutaneous and soft tissue manifestations of monkeypox. Skin and soft tissue features included: (A and D) vesicular or pustular lesions; B and C) macular lesions on palms and soles; (D and E) a subungual lesion; (F and G) more subtle papules and smaller vesicles; (H) and a deep abscess (arrow, image obtained during ultrasound-guided drainage).

Interpretation

Human monkeypox poses unique challenges, even for well-resourced healthcare systems with HCID networks.

Prolonged shedding of viral DNA from the upper respiratory tract after resolution of the skin lesion challenged current infection prevention and control guidance.

There is an urgent need for prospective studies of antivirals for this disease.

Added value of this study

Defined by the UK Health Security Agency as a high consequence infectious disease (HCID), our retrospective case series represents imported, nosocomial and domestic transmission of monkeypox, which has not been previously described in the UK. . We report the first use of antiviral agents in monkeypox patients, with three patients receiving brincidofovir and one receiving tecovirimat.

Brincidofovir was not found to confer any compelling clinical benefit and was associated with impaired liver function tests in all cases. The patient treated with tecovirimat had a shorter duration of symptoms and viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract than the rest of the patients in the series, with no adverse events identified before discharge.

Several of the patients experienced prolonged viremia and viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract after crusting of all skin lesions, leading to prolonged isolation in hospital.

Implications of all available evidence

Monkeypox is an emerging global health threat, capable of spreading across borders and subsequently transmitted. Although optimal infection control and treatment strategies have not been established for this potentially dangerous pathogen, our first-use data suggest that brincidofovir has poor efficacy; however, prospective studies of tecovirimat in human monkeypox are warranted.

The infection control implications of viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract should be considered in future outbreaks.

Contagion

Clinical picture

Diagnosis

Treatment and prevention

|

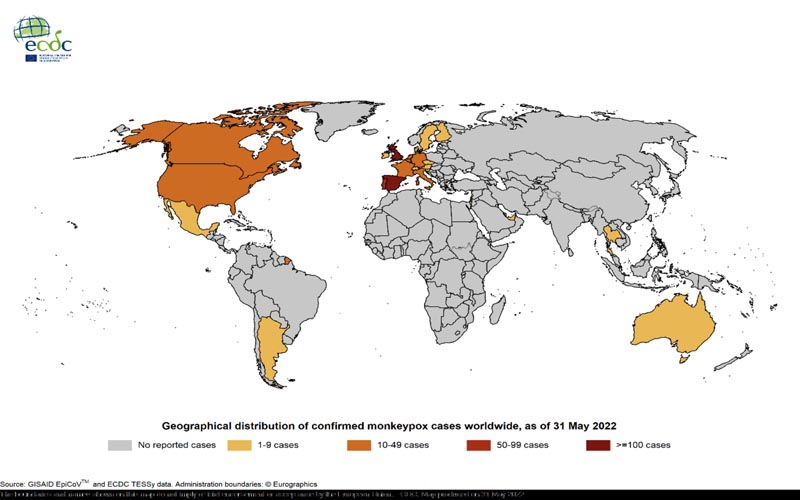

Global update : Since the beginning of the outbreak, a total of 557 cases have been confirmed worldwide. As of May 31, 2022 , cases have been confirmed in non-endemic European countries outside the EU/EEA, as well as in the Americas, Australia and Asia. Cases were reported in Argentina (2), Australia (2), Canada (26), Israel (2), Mexico (1), Switzerland (4), Thailand (1)*, United Arab Emirates (4), United Kingdom ( 179) and the United States (15). Most cases outside the UK, Canada and the US are reported to be travel-related. However, cases without known travel history, contact with other cases, animals, or specific events are also reported.