Background

Patients with preeclampsia show increases in placental leptin production in mid-gestation and an associated increase in plasma leptin levels in late gestation. The consequences of increases in leptin production during mid- and late pregnancy are unknown.

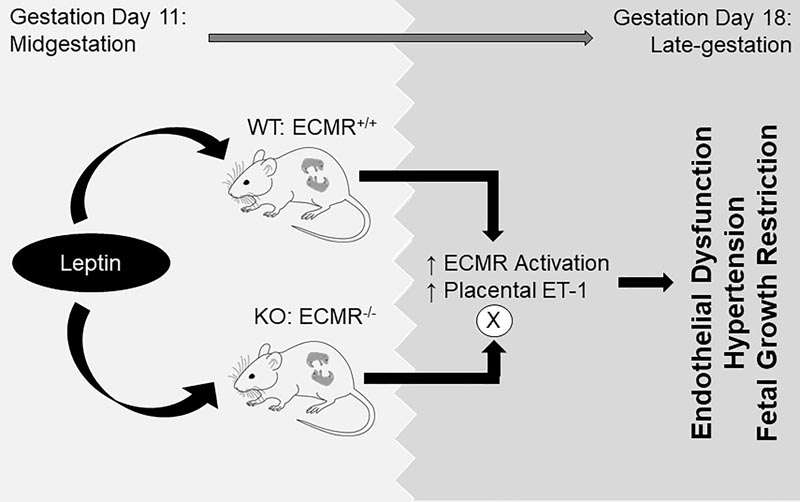

Our previous work indicates that leptin infusion induces endothelial dysfunction in non-pregnant female mice through leptin-mediated aldosterone production and activation of the endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor (ECMR), which is eliminated by deletion of ECMR.

Therefore, we hypothesize that leptin infusion at mid-gestation induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension, hallmarks of clinical preeclampsia, which are prevented by ECMR clearance.

Methods:

Leptin was infused via a miniosmotic pump (0.9 mg/kg per day) into ECMR intact (WT) and ECMR deletion (KO) littermates on gestation day (GD).

Results:

Leptin infusion decreased fetal weight and placental efficiency in WT mice compared to WT+ vehicle. Radiotelemetry recording demonstrated that blood pressure increased in WT mice infused with leptin during the infusion. Leptin infusion reduced endothelium-dependent relaxation responses to acetylcholine (ACh) in both resistance vessels (second-order mesenteric) and conduit vessels (aorta) in WT pregnant mice.

Leptin infusion increased placental production of ET-1 (endothelin-1) evidenced by increased expressions of PPET-1 (preproendothelin-1) and ECE-1 (endothelin-converting enzyme-1) in WT mice.

The expression of adrenal aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) and angiotensin II type 1 receptor b (AT1Rb) was increased by leptin infusion in pregnant WT mice. Pregnant KO mice demonstrated protection against leptin-induced reductions in pup weight, placental efficiency, increased BP, and endothelial dysfunction.

Conclusions:

Taken together, these data indicate that leptin infusion at midgestation induces endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and fetal growth restriction in pregnant mice, which is eliminated by deletion of ECMR.

Comments

Before a baby is born, critical supply chain problems with nutrition and oxygen can lead to premature birth or even death and increase the risk of lifelong cardiovascular disease for the child and mother.

Scientists have discovered that a mid-gestation increase in the hormone leptin , which most of us associate with appetite suppression , produces problematic blood vessel dysfunction and restriction of the baby’s growth in preeclampsia that puts the baby at risk. to mother and baby.

It is known that around 20 weeks of pregnancy, women with preeclampsia experience an increase in leptin production by the placenta, but the consequences are unknown.

“It’s emerging as a marker of preeclampsia ,” says Dr. Jessica Faulkner, a vascular physiologist in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia and corresponding author of the study in the journal Hypertension.

Leptin , produced primarily by fat cells, is also produced by the temporal organ, the placenta, which allows the mother to supply nutrients and oxygen to her developing baby, Faulkner says. Leptin levels rise steadily in a healthy pregnancy, but it is unclear specifically what leptin does even normally in this scenario. There is some evidence that it is a natural nutrient sensor in reproduction or perhaps a way to allow the growth of new blood vessels and/or stimulate growth hormone for normal development.

“But in patients with preeclampsia, leptin levels increase more than they should,” Faulkner says.

New research looking at the impact shows for the first time that increased leptin causes endothelial dysfunction in which blood vessels constrict, their ability to relax is affected and the baby’s growth is restricted.

When scientists inhibited the precursor of nitric oxide , a potent natural dilator of blood vessels, as occurs with hypertension, it virtually replicated the effect of the leptin increase in mid-gestation.

To make matters worse, scientists also have evidence that leptin plays a role in increasing levels of the blood vessel constrictor endothelin 1 .

In contrast, when they removed the aldosterone receptor , in this case the mineralocorticoid receptors on the surface of cells lining blood vessels, endothelial dysfunction did not occur, says Dr. Eric Belin de Chantemele, a physiologist at the Center for MCG Vascular Biology and author of the article.

“We think what happens in patients with preeclampsia is that the placenta doesn’t form properly,” Faulkner says. “At mid-gestation, fetal growth is not happening as it should. I think the placenta is compensating by increasing leptin production,” potentially with the goal of helping stimulate more normal growth. But the results seem to be quite the opposite.

“It can harm the baby’s development and increase the risk of long-term health problems for the baby and the mother,” she says.

While leptin has been associated with preeclampsia, this was the first study to show that when leptin increases, it induces the unhealthy clinical features of preeclampsia, says Belin de Chantemele.

When they infused leptin into pregnant mice to mimic the increase that occurs in preeclampsia, they saw an unhealthy chain reaction with the adrenal gland producing more of the steroid hormone aldosterone that could be increasing the production of endothelin 1, also by the placenta.

Their previous work has shown that outside of pregnancy, a leptin infusion produces endothelial dysfunction. Belin de Chantemele’s lab has pioneered work showing that fat-derived leptin directly prompts the adrenal glands to produce more aldosterone, which activates mineralocorticoid receptors found throughout the body, especially in the women’s blood vessels, which is important for blood pressure levels. High aldosterone levels are a hallmark of obesity and a leading cause of metabolic and cardiovascular problems.

That work led them to hypothesize that the leptin infusion that occurs mid-gestation in preeclampsia had a similar impact that removing the mineralocorticoid receptors that line blood vessels could resolve. They have connected similar physiological dots in young women in which obesity often robs them of the early years of protection against cardiovascular disease that women typically provide until menopause.

These same players are likely factors that increase the mother’s risk of lifelong cardiovascular problems, Faulkner says. “It means the system is dysregulated and that’s basically when you develop a disease,” she says.

Its goals include better defining pathways for increased blood pressure and other blood vessel dysfunctions, pathways that can be addressed during pregnancy to avoid potentially devastating outcomes for mother and baby, of what Faulkner characterizes as "a two-strike condition."

Their findings to date indicate that effective therapies to best protect mother and baby could be existing medications such as eplerenone , a blood pressure medication that binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor and effectively reduces the effect of higher levels. high levels of aldosterone, scientists say.

Problems are likely to begin with the placenta and potentially inadequate blood flow to the temporal organ early in its development and subsequent failure to develop the large blood vessels that become the passage of nutrients and oxygen from mother to baby. .

It is known that in preeclampsia there are problems such as decreased secretion of placental growth factor. The conclusion seems to be that at mid-gestation, the placenta can no longer adequately support the baby, which may be why it secretes leptin, possibly in an effort to stimulate its own growth and normal fetal development, but It actually contributes to cardiovascular health and fetal consequences, scientists report, including increasing the mother’s blood pressure.

“Unfortunately, rates of preeclampsia are increasing ,” says Faulkner, both in the number of pregnant women affected and the severity of them. According to an analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published in January of this year in the Journal of the American Heart Association , rates of hypertension that arise during pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, almost have doubled in rural and urban areas of this country between 2007 and 2019 and have accelerated since 2014. Gestational hypertension is an increase in a pregnant woman’s blood pressure in mid-gestation but without associated signs of protein in urine, a sign of kidney failure or markers of placental dysfunction, as found in preeclampsia.

Risk factors include having more than one fetus, chronic high blood pressure, type 1 or 2 diabetes, kidney disease, autoimmune disorders before pregnancy, as well as the use of in vitro fertilization. The rising rates of preeclampsia are primarily attributed to obesity , which is a risk factor for many of these conditions and is associated with high levels of aldosterone and leptin, says Faulkner. Other times, women seem to develop the problem spontaneously.

Next steps in research include better understanding how and why leptin increases more than it should, Faulkner says.

The scientists are supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.