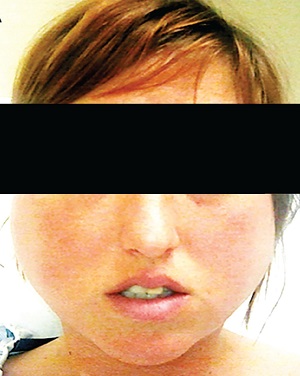

Presentation of a case • A 21-year-old woman with a history of depression and anxiety presents to the office for follow-up, referred from the emergency department where 2 days ago she was treated for a feeling of "fainting" during her participation in a sports competition match. • In the emergency department, a serum ionogram showed hypokalemia of 2.9 mEq/L (reference range 3.7–5.1 mEq/L), bicarbonate 35 Eq/L (22–30 mEq/L), and orthostatic hypotension. • The patient received 2 liters of isotonic saline intravenously and potassium (k+) intravenously and orally. At follow-up, her vital signs were normal and her body mass index is 24.5 kg/m2. She reports feeling better but she has noticed marked swelling of both lower extremities, which is causing her distress. • Physical examination is notable for 2+ pitting edema and calluses on the dorsum of his right hand. |

| A serious mental illness with physical consequences |

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a serious mental illness characterized by binge eating followed by compensatory purgative behaviors. It is frequently accompanied by medical sequelae that affect normal physiological functioning and contribute to higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

Most people with bulimia nerivosa are normal weight or overweight.

Often, people with BN are able to avoid detection of their eating disorder. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to become familiar with these complications and how to identify patients with patterns of eating disorders.

> Recurrent binges followed by purges

BN is characterized by an overvaluation of weight and body shape and by recurrent binge eating (consumption of an excessive amount of calories in a short period of time, usually a period of 2 hours, which the patient feels unable to control).

This is soon accompanied by compensatory purging behaviors, which may include abuse of laxatives and diuretics, omission of insulin injection (diabulimia or eating disorder-diabetes mellitus type 2), self-induced vomiting, fasting, and excessive physical exercise. Some patients also abuse caffeine or stimulant medications, commonly prescribed to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse account for more than 90% of purgative behaviors. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Ed. (DSM-5) requires episodes of binge eating and compensatory behaviors, occurring at least 1 time/week over the course of 3 months, and not occurring during an episode of anorexia nervosa. . The complications of purgative behaviors present in BN are identical to those of the anorexia nervosa subtype with binge-purge and not with anorexia nervosa with restriction, mainly of calories, without excessive weight loss.

The severity of BN is determined by the mode frequency of purging behaviors (mild, an average of 1 to 3 compensatory purging episodes per week; moderate, 4–7; severe, 8–13; extreme, ≥14) or the degree of functional impairment. Some patients may vomit several times a day, while others may use significant amounts of laxatives.

Some may practice multiple purging behaviors. Exercise is considered excessive if it interferes with other activities, persists despite injuries or medical complications, or is practiced at inappropriate times or situations.

| It begins in adolescence and is quite common |

BN typically develops in adolescents or young adults. It affects both sexes, although it is much more common in girls and young women. The condition does not depend on a person’s sexual orientation, but it has been shown to be more prevalent in non-heterosexual men.

Research has found a similar prevalence of BN among different racial and ethnic groups. Individuals with BN are usually within or above the normal weight range. According to WHO pooled data, the lifetime prevalence of BN in adults is 1.0%, using the DSM-IV Major Criteria. This level of prevalence is higher than the prevalence of anorexia nervosa. Prevalence estimates are higher using the DSM-5 Expanded Criteria, ranging from 4% to 6.7%.

There are multiple predisposing and perpetuating factors: genetic, environmental, psychosocial, neurobiological and temperamental. These may include impulsivity; developmental transitions, such as puberty; internalization of the thin ideal and concerns about weight and body shape. A history of childhood trauma, including sexual, physical, or emotional trauma, has also been associated with BN.

More than 70% of people with eating disorders report psychiatric comorbidity: affective disorders, anxiety, substance abuse, and personality disorders. Psychiatric comorbidities as well as hopelessness, shame, and impulsivity associated with the illness may contribute to challenges with non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal ideation, and death by suicide.

Individuals with BN experience lifetime rates of non-suicidal self-harm of 33% and are almost 8 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. Mortality rates in those with BN are lower than in those with anorexia nervosa, but still remain high at 1.5% to 2.5%.

| Medical complications |

BN is associated with a significantly higher mortality rate, although many of the patients are young.

Much of this high mortality is attributable to associated medical complications, which are a direct result of the mode and frequency of purging behaviors. So, for example, if someone uses laxatives 3 times a day or vomits 1 time a day, they may have no medical complications, but many patients practice their purging behaviors many times a day, which causes multiple complications.

Aside from electrolyte disturbances resulting from purging, other medical complications depend on the particular mode of purging. On the other hand, BN has been proven to increase the risk of any cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease and death in women. These same complications can also be observed in patients with anorexia nervosa who experience binge-purge, in contrast to those with anorexia nervosa who only restrict caloric intake, without resorting to purging.

| Fur |

> Russell’s sign

Russell’s sign was first defined in BN by Dr. Gerald Russell in 1979 and refers to the development of calluses on the dorsal aspect of the dominant hand. It is pathognomonic of self-induced vomiting and is due to traumatic irritation of the hand by the teeth, due to repeated insertion of the hand into the mouth to cause vomiting. This sign does not appear in patients who can vomit spontaneously or who use utensils to induce vomiting.

| Teeth and mouth |

Abnormalities of the teeth and mouth specific to purging by vomiting include erosions and trauma to the oral mucosa and pharynx. Dental erosion is the most common oral manifestation of chronic regurgitation.

It is believed to be caused by teeth coming into contact with acid vomit (pH 3.8), although it is not clear how the composition of saliva is modified and how it contributes to dietary intake. It tends to affect the lingual surfaces of the maxillary teeth and is known as perimyolysis.

Vomiting also potentially increases the risk of tooth decay. There may also be signs of trauma to the oral mucosa, especially to the pharynx and soft palate, and it is presumed to occur as a result of the patient introducing a foreign object into the mouth to induce vomiting, or from the caustic effect of the vomiting on the mucosal lining.

Once they have developed, dental erosions are irreversible. After purging, the use of fluoride mouthwash and gentle horizontal brushing are recommended. Continuous self-induced vomiting also damages newly implanted teeth and dentures.

| Head, ears, nose and throat |

Purging by vomiting increases the risk of subconjunctival hemorrhages from severe retching, which can also cause recurrent epistaxis. In fact, recurrent episodes of epistaxis that remain unexplained should raise suspicion of covert BN.

Pharyngitis is usually seen in those who vomit frequently, due to contact of pharyngeal tissue with stomach acid. Hoarseness, cough, and dysphagia may also develop. Pharyngeal and laryngeal discomfort can be improved by stopping vomiting and using medications to suppress acid production, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

| parotid glands |

More than 50% of people with purgative behaviors through self-induced vomiting present hypertrophy of the parotid gland or sialadenosis .

> Salidenosis

It is noteworthy that this hypertrophy usually develops 3 to 4 days after the cessation of purging. Symptoms are painless bilateral enlargement of the parotid gland and sometimes other salivary glands. It is believed to be due to cholinergic stimulation of the glands; glandular hypertrophy to satisfy the demands of hypersalivation or the excessive reserve of saliva that, when vomiting stops, is no longer needed. The histopathological study reveals hypertrophy of the acinar cells with preservation of the rest of the architecture, without signs of inflammation.

Swelling may disappear with cessation of purging. The partial decrease in glandular hypertrophy is highly suggestive that the purge continues. Sialadenosis also tends to resolve with the use of sialagogues such as sour candies, heating pads, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which also have a therapeutic role, and should perhaps be initiated prophylactically in those with a long history of vomiting. excessive and are undergoing treatment to stop the purge. In rare refractory cases, pilocarpine can be used judiciously to shrink the glands back to normal size.

| Cardiovascular |

Specific cardiac complications of purging include electrolyte disturbances due to vomiting and abuse of diuretics or laxatives.

These disorders are also accompanied by serious cardiac arrhythmias and prolongation of the QT interval, especially as a result of hypokalemia and acid-base disorders. Excessive ingestion of ipecac, which contains the cardiotoxic alkaloid emetine, used to induce vomiting, can cause various conduction disturbances and potentially irreversible cardiomyopathy.

Abuse of caffeine or stimulant medications, used to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, can cause palpitations, sinus tachycardia, or arrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardia. Similarly, diet pills, whose use has increased in this population, are associated with arrhythmias.

| Pulmonary |

Retching during vomiting increases intrathoracic and intraalveolar pressures, which can lead to pneumomediastinum . This pathology is due to non-traumatic alveolar rupture in the setting of malnutrition and, therefore, is nonspecific and does not allow us to differentiate patients who purge from those who restrict themselves.

Vomiting also increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia , which may be involved in the so far enigmatic pathogenesis of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary infection .

| Gastrointestinal |

Gastrointestinal complications depend on the purging mode used. Upper gastrointestinal complications develop in those who induce vomiting, while lower gastrointestinal complications appear in those who abuse stimulant laxatives.

> Esophageal complications

Excessive vomiting exposes the esophagus to gastric acid and damage to the lower esophageal sphincter, increasing the susceptibility to gastroesophageal reflux disease and other esophageal complications, including Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. However, it is not clear whether this is truly an association between purging by self-induced vomiting and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Although research indicates that in patients who purge the majority of gastrointestinal complications are due to reflux, and that this can occur when those who purge are evaluated by pH monitoring, endoscopic findings do not necessarily correlate with the severity of symptoms. This suggests a possible functional component in gastrointestinal reflux-related complications.

As treatment, cessation of purging is recommended, although PPIs can be tried. Metoclopramide may also be beneficial, due to its actions of accelerating gastric emptying and increasing the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. If the symptoms continue or have been present for a long time, endoscopy is indicated to look for precancerous abnormalities of the esophageal mucosa, as occurs with Barrett’s esophagus.

Rupture of the esophagus , known as Boerhaave syndrome, and Mallory-Weiss tears are rare complications that can cause bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract, following recurrent episodes of emesis.

Mallory-Weiss tears commonly present as blood-streaked or bloody vomiting or coffee grounds-like emesis after recurrent vomiting episodes. Blood loss from such tears is usually minimal. On endoscopy, Mallory-Weiss tears appear as longitudinal mucosal lacerations.

> Colonic inertia

Individuals who use excessive amounts of stimulant laxatives, and their chronic abuse, may be at risk for "cathartic colon," a condition in which the colon becomes an inert tube, unable to pass stool. This is believed to be due to direct damage to the myenteric nerve plexus.

However, at present, it is doubted whether this condition actually develops in people with eating disorders and use of stimulant laxatives. Regardless, in general, stimulant laxatives should be used only short-term, to avoid this potential complication, and should be discontinued in those who develop this condition. On the other hand, to manage constipation, osmotic laxatives can be prescribed in a measured manner, since they do not directly stimulate peristalsis.

Melanosis coli is a black discoloration of the colon of no known clinical significance, often reported during colonoscopy in those who abuse stimulant laxatives.

Rectal prolapse can also develop in those who abuse stimulant laxatives, but it is nonspecific for this mode of purging, as it can also develop solely as a consequence of malnutrition and weakness of the pelvic floor muscles.

| Endocrine |

A possible endocrine complication of BN is the irregular menstrual cycle, compared to the frequently observed amenorrhea in both restraint and binge-purge subtypes of anorexia nervosa. Although patients with BN do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of bone demineralization, as occurs in patients who restrict calories.

In people with a history of anorexia nervosa with binge-purge, it is advisable to perform bone densitometry using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus may manipulate their blood glucose levels as a way to purge calories, a condition previously called eating disorder type 1 diabetes mellitus (formerly known as diabulimia). These patients are at risk for marked hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis, and premature microvascular complications such as retinopathy and neuropathy.

| Metabolic and electrolyte alterations |

In addition to the aforementioned complications, each of the purging methods used by patients with BN may be associated with specific electrolyte disturbances. These alterations are probably the closest cause of death in patients with BN. When a patient uses multiple modes of purging behaviors simultaneously, as well as their psychiatric illness worsening, electrolytes may also be altered.

Electrolyte alteration profiles may overlap and be more extreme. For patients with a history of known purging behaviors, electrolytes should be assessed frequently, even daily, depending on the frequency of their purging behaviors, with the most common being self-induced vomiting.

Patients who purge with self-induced vomiting or diuretic abuse, or both, present with hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis. The severity of electrolyte abnormalities worsens with the frequency of vomiting. Similarly, laxative abuse also results in hypokalemia and hypochloremia. However, they may present metabolic acidosis without anion gap or metabolic alkalosis, depending on the chronicity of laxative abuse.

In general, chronic diarrhea leads to metabolic alkalosis. Hyponatremia may also be present with these 3 purging behaviors. In these cases, the most common finding is hypovolemic type hyponatremia due to chronic fluid depletion as a result of purging behaviors.

> Pathophysiology of hypokalemia and hypochloremia

The pathophysiological causes of hypokalemia and hypochloremia are observed regardless of purging behavior. The first, and most obvious, is that there is a loss of K+ in the purged gastric contents, excessive feces resulting from laxative abuse, or urine due to diuretic abuse.

Second, chronic purging results in fluid depletion, which is detected by the afferent arteriole of the kidney as decreased renal perfusion pressure, which in turn activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, resulting in a increased production of aldosterone by the zona glomerularis of the adrenal glands. Aldosterone acts on the distal convoluted tubules and cortical collecting ducts, thereby reabsorbing sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) in the body’s attempt to prevent severe dehydration, hypotension, and fainting.

Aldosterone also promotes renal secretion of K+ into the urine and thus hypokalemia occurs. This K+ loss mechanism is actually a major contributor to hypokalemia, rather than gastrointestinal or urinary losses.

Regarding the abuse of diuretics, these drugs, by themselves, act directly on the kidney to promote the loss of urinary NaCl, leading to hypovolemia and aldosterone secretion. This results in urinary loss of hydrogen (H+) and K+, causing metabolic alkalosis. However, potassium-sparing diuretics such as spironolactone do not precipitate metabolic alkalosis, since they inhibit the action of aldosterone in the kidney.

Table 1

| Behavior | Potassium | Sodium | acid base | |

| Low | Low or normal | metabolic alkalosis | |

| Low | Low or normal | Metabolic alkalosis or non-anion gap acidosis | |

| Diuretic abuse | Low | Low or normal | metabolic alkalosis |

| Pseudo Bartter syndrome |

The aforementioned hydroelectrolyte results due to the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system are known as pseudo-Bartter syndrome, due to the serum and histochemical findings in the renal biopsy, which resemble those of Bartter syndrome. However, the findings are not due to an intrinsic renal pathology but rather are the result of the state of chronic dehydration, due to purgative behavior.

The increased level of aldosterone that results from purging behaviors, and which is an integral component of pseudo-Bartter syndrome, when purging behaviors stop abruptly can lead to edema. The reason is that serum aldosterone levels remain elevated, causing salt and water retention, even though the patient is no longer losing fluid, since purging has ceased.

| Evaluation and Management of Electrolyte Disorders and Pseudo Bartter Syndrome |

It is important to suspect covert purging behaviors in otherwise healthy young women who present with hypokalemia without an underlying medical cause. However, hypokalemia alone is not specific for purgative behaviors.

If the patient does not report pure behavior when questioned, a diagnostic aid is to collect a urine sample to determine the level of K+, creatinine, Na+, and Cl-). A urinary K+/creatinine ratio <13 can identify hypokalemia resulting from gastrointestinal loss, diuretic use, poor intake, or transcellular changes. The urinary Na+/Cl- ratio can also be calculated.

Vomiting is associated with a urinary Na+/Cl- ratio >1.6, in the setting of hypokalemia, while laxative abuse is associated with a lower ratio (0.7). Chronic hypokalemia is usually asymptomatic and can be corrected slowly. If potassium is not <2.5 mEql/l and the patient does not have physical symptoms or electrocardiographic changes of hypokalemia, hypokalemia can be controlled by stopping purging behavior and administering oral potassium.

Adherence to oral supplemental potassium administration can be improved by using potassium chloride tablets instead of liquid preparations. Aggressive intravenous K+ supplementation puts patients at risk for hyperkalemia and should be reserved for critically low potassium levels.

Severe hypokalemia ( <2.5 mEq/L) requires K+, both oral and intravenous. This replacement process is aided by administering isotonic saline with potassium chloride intravenously at a low infusion rate (50-75 ml/hour). To correct metabolic alkalosis and interrupt the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, it is necessary to correct volume depletion.

Untreated severe hypokalemia can lead to a prolonged corrected QT interval, with posterior torsades de pointes and other life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Simply correcting hypokalemia without correcting metabolic alkalosis is not sufficient, because renal K+ loss continues due to the action of renal aldosterone. Rarely, chronic hypokalemia is associated with acute renal failure and signs of interstitial nephritis on renal biopsy, which has been termed hypokalemic nephropathy.

Mild hyponatremia is often self-correcting by stopping purging behaviors and engaging in oral rehydration. However, if serum Na+ is <125 mEql/l, hospitalization is indicated, for close monitoring and slow correction with isotonic saline, until reaching infusion values of 4 to 6 mEql/l every 24 hours.

This prevents the serious complication known as central pontine myelinolysis. If hyponatremia is severe (serum Na+ <118 mEql/l), the patient is likely to benefit from admission to an intensive care unit and nephrology consultation, to consider administering desmopressin to avoid overcorrection.

Metabolic alkalosis may develop in patients with BN, as a result of decreased intravascular volume, elevated aldosterone, and hypokalemia. Most of the time it does not respond to saline.

The urinary Cl value can also be used; if <10 mEq/L, the metabolic alkalosis is hypovolemic and will improve with slow replacement of intravenous saline. The physical examination also allows us to determine the patient’s fluid volume, looking for signs of dehydration.

Because of the underlying risk of pseudo-Bartter syndrome in BN patients who abruptly discontinue purging behaviors, aggressive fluid resuscitation should be avoided. Discontinuation of purgative behavior coupled with rapid intravenous fluid resuscitation can result in marked and rapid edema formation, with weight gain, which can be psychologically distressing.

Therefore, to mitigate edema formation, a low saline infusion rate (50 ml/hour), with low doses of spironolactone (start: 50-100 mg, maximum dose 200-400 mg/day) should be used. .

Spironolactone is usually continued for 2-4 weeks and then reduced to 50 mg every few days. Occasionally, in patients who abuse extreme laxatives, the propensity for edema may persist, requiring even slower administration of spironolactone.

| Medical complications of binge eating |

The literature on the complications of binge eating, specific to BN, is limited. However, patients with binge eating disorders tend to be overweight or obese because they do not purge after binge eating episodes.

Therefore, many of the medical complications in binge eating disorder, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver, and metabolic syndrome, are related to obesity. In contrast, many patients with BN have a normal body mass index.

Therefore, it is difficult to infer that the medical complications resulting from binge eating are the same as those that occur from binge eating in BN. However, extrapolation makes sense in some cases. For example, patients who binge eat are at higher risk for deficiencies because the food eaten during a binge tends to be processed, high in fat and carbohydrates, and low in protein.

A diet low in vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A and C, increases the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

On the other hand, patients with binge eating disorders have more gastrointestinal symptoms: acid reflux, dysphagia, and bloating, which are also seen in BN. Therefore, binge eating can influence these symptoms.

Finally, less commonly, gastric perforation has been observed during a binge eating episode due to excessive distention of the stomach, resulting in gastric necrosis. In these cases, gastric outlet obstruction due to the formation of an alimentary bezoar has also been reported.

| Identification and treatment of mental health |

It has been shown that the Eating Disorder Screen applied in primary care effectively detects patients with these disorders. It consists of 5 questions:

• Are you satisfied with your eating pattern? ("No", is considered an abnormal response). • Do you ever eat in secret? ("Yes", it is an abnormal answer to stop this and the rest of the questions). • Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself? • Has any member of your family suffered from an eating disorder? • Do you currently suffer or have you suffered in the past from an eating disorder? |

Cotton et al. found that ≥2 abnormal responses have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 71% for eating disorders.

Standard mental health treatments in patients with BN include nutritional stabilization and interruption of purgative behavior, monitoring and appropriate management of associated medical complications, prescribing medications according to clinical indication, and psychotherapeutic interventions. The recommended initial therapy for the treatment of BN is cognitive behavioral therapy.

A recent meta-analysis guided cognitive-behavioral self-help and a specific form of cognitive-behavioral therapy individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders. This treatment continues until complete remission is achieved. No specific drug has been developed for the treatment of BN. In the US, the only drug approved for BN is the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SIRS) fluoxetine.

It is administered until a target dose of 60 mg/day is reached, regardless of whether or not there are comorbidities. This dose reduces the frequency of binge eating and purging episodes significantly more than 20 mg/day and placebo. It is recommended for patients who do not respond adequately to psychotherapeutic interventions.

Table 2

| Fluoxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bulimia nervosa. |

| Co-occurring anxiety and depression should be treated with therapy and pharmacologically. |

| Stimulant medications have not been evaluated in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. |

Other SIRS along with the antiepileptic topiramate have shown modest efficacy. Bupropion is contraindicated in the treatment of BN due to an increased risk of seizures. No clinical trials have evaluated stimulant medications for the treatment of BN. Often, stimulant medications are stopped until there is a period of withdrawal from purging behaviors.

During withdrawal follow-up, off-label use of stimulation could be reconsidered if binge eating behavior persists, or if attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is comorbid, or both.

In general, concomitant treatment of coexisting anxiety or depression should be done. SIRS like fluoxetine also target these symptoms. If treatment with fluoxetine has failed, then second-line medications such as sertraline or escitalopram may be indicated. Citalopram is not typically used due to the increased risk of QT prolongation. Paroxetine is also not used due to its potential for weight gain.

| Forecast |

The greater the psychosocial dysfunction and body image disturbance, the greater the risk of relapse.

In patients requiring hospitalization, several factors predict a poor outcome, including fewer years of follow-up, more attempts to lose weight, older age at the start of treatment, and more deterioration in overall functioning.

Recovery is possible, with variable remission rates, depending on the type of study and the definition of remission used (38% to 42%, at 11 and 21 years, respectively. 65% of the individuals in the study were followed for 9 and 22 years old.

| Conclusion |

Bulimia nervosa is a complex psychiatric illness with countless medical complications, some of which can be life-threatening. Most morbidity and mortality in patients with bulimia nervosa is the direct result of purging behaviors and the resulting electrolyte and acid-base disorders.

Therefore, it is important for clinicians to become familiar with these complications since most patients are of normal weight and can often avoid detection of their eating disorder.

| Continuation of the case presented |

On the first office visit, the patient is discharged without future follow-up appointments, without having undergone any interventions or biochemical analyses. The doctor did not find Russell’s sign and informed the patient that the edema was due to the fluids administered in the emergency department and would resolve on its own. The patient again had purgative behaviors with greater vigor when she perceived her weight gain, as a result of the edema.

One month later, she suffered a syncopal episode during another exhaustive physical exercise, which required the administration of oral and intravenous K+ and saline. During follow-up, the doctor checks for worsening of the edema and recognizes the Russell sign. Laboratory tests reveal mild hypokalemia. With these findings, she requests screening for an eating disorder.

The screening is positive and the patient confesses that she adopts purgative behaviors through daily self-induced vomiting, abuse of stimulant laxatives, and episodes of binge eating. She is referred to the eating disorder specialist and begins treatment with 40 mmEq/day of potassium chloride, and plans weekly follow-up laboratory tests, until specialized treatment begins.