Inaccurate diagnoses of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were common, especially among older adults, those with dementia, and patients presenting with altered mental status in this study of 17,000 hospitalized adults treated for pneumonia across 48 Michigan hospitals. Full courses of antibiotics in patients misdiagnosed with CAP can be harmful.

In this cohort study of 17,290 hospitalized adults treated for pneumonia across 48 Michigan hospitals, 12% were diagnosed inappropriately. Older patients, those with dementia, and those with altered mental status had the highest risk of being misdiagnosed. For those misdiagnosed, receiving a full course of antibiotics was linked to antibiotic-related adverse events.

Lower respiratory tract infections, including CAP, are the fourth most common cause of medical hospitalization and the leading infectious cause of hospitalization in the U.S. While many patients hospitalized for pneumonia do indeed have infections, inaccurate or inappropriate diagnoses of pneumonia (i.e., diagnosing pneumonia when it is not present) are common.

Although some misdiagnoses of CAP are inevitable due to diagnostic uncertainty when patients are first admitted, many continue to be misdiagnosed even after discharge. Misdiagnosis of CAP can harm patients by delaying recognition and treatment of acute (e.g., heart failure exacerbations), chronic, or new conditions (e.g., lung cancer) and can lead to unnecessary antibiotic use, adverse effects, and antibiotic resistance.

Precisely quantifying the proportion of patients treated for CAP who receive an inaccurate diagnosis has been challenging due to the lack of validated definitions. In 2022, we developed a metric to quantify CAP misdiagnosis, which was validated and later endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF). This paper applies this metric to a cohort of hospitalized patients treated for CAP across 48 Michigan hospitals to understand the epidemiology and outcomes associated with CAP misdiagnosis.

This prospective cohort study, involving medical record reviews and patient follow-up calls, was conducted in 48 Michigan hospitals. Trained data extractors retrospectively evaluated hospitalized patients treated for CAP between July 1, 2017, and March 31, 2020.

Patients were eligible if they were adults admitted to general care with a discharge diagnosis code for pneumonia and received antibiotics on day 1 or 2 of hospitalization. Data were analyzed from February to December 2023.

Inaccurate CAP diagnosis was defined using an NQF-endorsed metric as antibiotic therapy for CAP in patients with fewer than two signs or symptoms of CAP or negative chest imaging.

Risk factors for inaccurate diagnosis were assessed, and for those misdiagnosed, 30-day composite outcomes (mortality, readmission, ER visit, Clostridioides difficile infection, and antibiotic-related adverse events) were documented and stratified by full (>3 days) versus short antibiotic treatment (≤3 days) using generalized estimating equation models adjusting for confounding factors and treatment propensity.

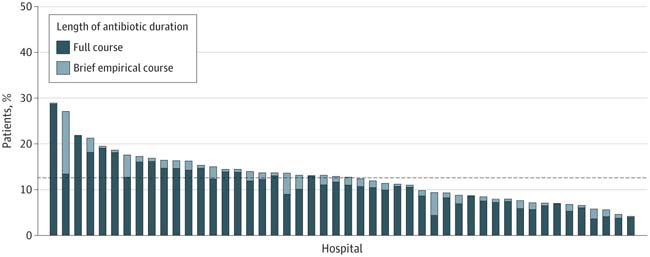

Of the 17,290 hospitalized patients treated for CAP, 2,079 (12%) met criteria for inaccurate diagnosis (median age [IQR], 71.8 [60.1–82.8] years; 1,045 [50.3%] women), of whom 1,821 (87.6%) received a full course of antibiotics.

Compared to appropriately diagnosed CAP patients, those inaccurately diagnosed were older (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11 per decade), more likely to have dementia (AOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.55-2.08), or altered mental status at presentation (AOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.39-2.19).

Among the misdiagnosed, the 30-day composite outcomes for full versus short antibiotic treatment did not differ significantly (25.8% vs. 25.6%; AOR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.79-1.23).

However, full treatment was associated with more antibiotic-related adverse events (31 of 1,821 [2.1%] vs. 1 of 258 [0.4%]; P = 0.03).

Figure: Patients treated for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) who were misdiagnosed. A full course of antibiotics was defined as more than 3 days of therapy, while a short course was 3 days or less. Each bar represents a hospital (N = 48), and the dashed line indicates the average proportion of inaccurate diagnoses across all hospitals during the study period.

In this cohort study, misdiagnosis of CAP among hospitalized adults was common, particularly among older adults, those with dementia, and those with altered mental status. Full antibiotic courses for patients misdiagnosed with CAP may be harmful.

We applied a novel, validated metric to a unique dataset of manually collected records from hospitalized CAP patients and found that approximately 1 in 8 patients was misdiagnosed. Most hospitals inaccurately diagnosed more than 10% of their patients. Those at highest risk for misdiagnosis were older adults, individuals with dementia, or those with altered mental status. Overall, nearly 88% of patients misdiagnosed with CAP received a full course of antibiotics, which was associated with physician-documented adverse antibiotic-related events.

First, because CAP is common, clinicians are at high risk of cognitive biases such as availability bias (i.e., the tendency to make decisions based on information that comes most readily to mind).

Second, CAP symptoms are nonspecific and can overlap with other cardiopulmonary diseases (e.g., congestive heart failure exacerbation), making diagnosis challenging. Given the poor outcomes associated with CAP, in situations of diagnostic uncertainty, healthcare professionals may prefer overtreatment over missing a CAP diagnosis.

Third, historical quality metrics imposed by organizations like The Joint Commission (e.g., requiring antibiotics within 6 hours of presentation) may have inadvertently led to more inappropriate CAP diagnoses. These measures, in effect during the 2000s and 2010s, may continue to influence clinician behavior regarding diagnosis.

Finally, previously published data show a correlation between CAP misdiagnosis and urinary tract infection misdiagnosis at the hospital level, suggesting that local policies, procedures, or culture may influence diagnostic accuracy.

This cohort study has important clinical and policy implications. As hospitalizations for CAP are common, so are inaccurate diagnoses of CAP. The risks of misdiagnosis are not evenly distributed across all populations: the most vulnerable groups are at the highest risk of receiving an inaccurate diagnosis. These same vulnerable populations are also more likely to suffer from adverse antibiotic events and resulting morbidity. Thus, balancing the harms of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of CAP remains essential.