Receiving touch is of vital importance, as many studies have demonstrated that touch promotes physical and mental well-being. We conducted a preregistered systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42022304281) and a multilevel meta-analysis covering 137 studies in the meta-analysis and 75 additional studies in the systematic review (n = 12,966 people, searched via Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science up to October 1, 2022) to identify critical factors that moderate the effectiveness of touch interventions. The studies consistently included a touch intervention versus no touch intervention with various health outcomes as dependent variables. The risk of bias was assessed through small studies, randomization, sequencing, performance bias, and attrition.

Touch interventions were particularly effective in regulating cortisol levels (Hedges´ g = 0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24 to 1.31) and increasing weight (0.65; 95% CI: 0.37 to 0.94) in newborns, as well as reducing pain (0.69; 95% CI: 0.48 to 0.89), feelings of depression (0.59; 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.78), and state (0.64; 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.84) or trait anxiety (0.59; 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.77) in adults.

Comparison of touch interventions involving objects or robots yielded similar physical benefits (0.56; 95% CI: 0.24 to 0.88 versus 0.51; 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.64) but smaller mental health benefits (0.34; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.49 versus 0.58; 95% CI: 0.43 to 0.73). Clinical cohorts of adults benefited more in mental health domains compared to healthy individuals (0.63; 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.80 versus 0.37; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.55). No differences in health benefits in adults were found when comparing touch administered by a familiar person or a healthcare professional (0.51; 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.73 versus 0.50; 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.61), but parental contact was more beneficial for newborns (0.69; 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.88 versus 0.39; 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.61).

It is necessary to consider the small but significant bias of small case studies and the impossibility of blinding experimental conditions. Leveraging factors that influence the effectiveness of touch interventions will help maximize the benefits of future interventions and focus research in this field.

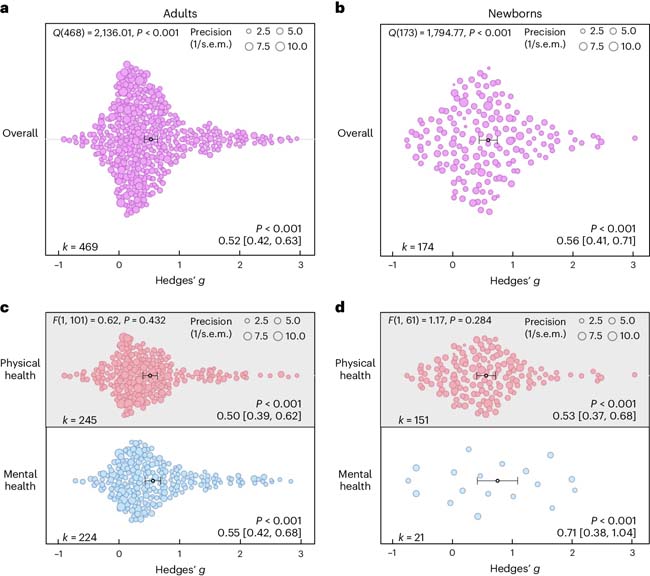

Figure: Benefits of Touch on Physical and Mental Health. a. Orchard plot illustrating overall benefits across health outcomes for adults/children in 469 effect sizes, partially dependent, from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. b. Same as a, but for newborns in 174 effect sizes, partially dependent, from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. c. Same as a but separating physical versus mental health benefits in 469 effect sizes, partially dependent, from 85 studies and 103 cohorts. d. Same as b but separating physical versus mental health benefits in 172 effect sizes, partially dependent, from 52 studies and 63 cohorts. Each point reflects a measured effect and the number of effects (k) included in the analysis is shown in the lower left. Mean effects and 95% CIs are presented in the lower right and indicated by the central black dot (mean effect) and its error bars (95% CI). The Q statistic for heterogeneity is presented in the upper left. Overall moderator impact effects were assessed using an F-test, and post hoc comparisons were conducted using t-tests (two-tailed). Note that P-values above mean effects indicate if an effect significantly differed from zero. P-values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. The point size reflects the precision of each individual effect (larger is more precise).

Touch can do a lot of good; so far, so good. But how much do humans benefit from it? How much contact is allowed? Who should touch and where? When we experience physical contact, does it even have to be with another human being? To answer these questions, a research team from Bochum, Duisburg-Essen, and Amsterdam analyzed over 130 international studies with around 10,000 participants. The researchers demonstrated that what touch actually does is relieve pain, depression, and anxiety. While frequent contact has a particularly beneficial effect, there is evidence that the contact does not need to last a long time. The effect is enhanced by skin-to-skin contact. In particular, touch administered by objects such as social robots, weighted blankets, and body pillows also showed a measurable effect. The team published their findings in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

For babies, touch should be administered by parents.

"We were aware of the importance of touch as a health intervention," says Dr. Julian Packheiser from the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at Ruhr University Bochum. "But despite many studies, it is still unclear how to use it optimally, what specific effects can be expected, and what the influencing factors are." After the extensive meta-analysis, the team was able to answer many of these questions.

Both adults and babies benefit from touch. "In the case of babies, it is important that touch is administered by the parents; their touch is more effective than that of a healthcare professional," says Dr. Helena Hartmann from Duisburg-Essen University. "In adults, however, we found no differences between people familiar to our volunteers and a nursing professional." The greatest effect of touch on adults was demonstrated by numerous studies on the participants´ mental state. According to these studies, pain, depression, and anxiety decreased significantly. Touch also had a positive effect on cardiovascular factors such as blood pressure and heart rate, but the effect was less pronounced.

Even a brief hug makes a difference.

A longer duration of contact, which averaged 20 minutes in the studies, did not significantly affect the outcome. “It is not true that the longer you touch, the better,” summarizes Julian Packheiser. Brief but more frequent contact turned out to be more beneficial. "It doesn´t have to be a long and expensive massage," says the researcher. "Even a brief hug has a positive impact." The researchers were surprised by the positive effect of touch applied by objects. Social robots, stuffed animals, body pillows, and similar items had worse outcomes than humans regarding mental health factors but still showed a measurable positive effect.

"This led us to the conclusion that consensual contact improves the well-being of patients in clinical settings and of healthy individuals," says Julian Packheiser. "So, if you feel like hugging family or friends, don´t hold back, as long as the other person consents."

Questions remain unanswered.

For researchers, this raises many more questions about the potential of touch interventions for public health. For example, the quality of touch experienced by people was not clear in the studies. Another unresolved issue is whether affective touch has a different effect than instrumental touch, such as hair washing by a hairdresser or examinations by a doctor. The role of touching animals and cultural differences between different communities has also not been sufficiently researched.

We provide clear evidence that touch interventions are beneficial across a wide range of physical and mental health outcomes, for both healthy and clinical cohorts, and across all ages. These benefits, although influenced in magnitude by study cohorts and intervention characteristics, were strongly present, leading to the conclusion that touch interventions can be systematically employed across the population to preserve and improve our health.

Reference: Packheiser, J., Hartmann, H., Fredriksen, K. et al. A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions. Nat Hum Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01841-8