The present study focused on understanding the relationship between childhood poverty and insulin resistance (IR), as well as the biological (i.e., cellular aging) and psychological (i.e., perceived life chances) mechanisms that may be the foundation of this partnership for African Americans in the rural southeastern United States. This demographic is among the most disadvantaged populations in the United States in terms of life expectancy and is at increased risk for several chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiometabolic disease.

Existing research on these health disparities has tended to focus on contemporary social factors, such as socioeconomic status and access to healthcare resources. However, a growing body of research suggests that these health disparities develop across the lifespan, with pathogenic processes beginning in childhood but not manifesting clinically until middle and late adulthood.

To help explain the developmental origins of racial health disparities, lifespan perspectives on health emphasize the ways in which socioeconomic and other stressors experienced during childhood “get under the skin” to portend health disparities in adulthood.

As summarized in Geronimus’s (2006) influential “wear and tear” hypothesis , chronic stress wear and tear, beginning in childhood and continuing throughout the life course, affects multiple physiological systems. This wear and tear, in turn, initiates a cascade of physiological processes involved in the deterioration of these systems, including premature aging of cells, in a way that ultimately leads to disease and an overall shorter lifespan.

With respect to insulin resistance , recent research has demonstrated the relevance of childhood adversity in explaining racial disparities. Fuller-Rowell et al. (2019), for example, found that a composite risk index of childhood adversity was positively associated with insulin resistance in middle-aged adults and, when accounted for, attenuated 18% of racial differences in resistance to insulin. This study also found support for inflammation and cortisol as mediating variables, suggesting the potential for stress-related biological mechanisms underlying this association.

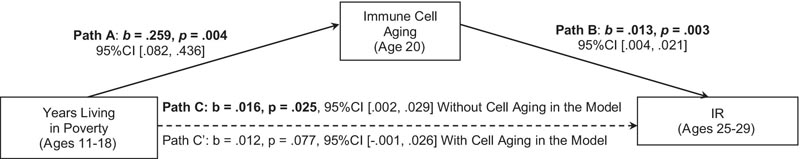

Summary The present study investigated developmental pathways that may contribute to chronic diseases among rural African Americans. Using a sample of 342 African American youth (59% female) from the southeastern United States followed for nearly two decades (2001-2019), we examined the prospective association between family poverty during adolescence (ages 11-18) and resistance to insulin (IR) in young adulthood (between 25 and 29 years), as well as the underlying biological and psychosocial mechanisms. Results indicated that family poverty during adolescence predicted higher levels of IR in young adulthood, with accelerated aging of immune cells in the 20s partially mediating this association. Serial mediation models confirmed the hypothesized pathway linking family poverty, perceived life chances, cellular aging, and IR. The findings provide empirical support for the theoretical developmental precursors of chronic diseases. |

Immune cell aging as a mediator of the relationship between years of poverty and IR. Control variables not shown. Unstandardized coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. n = 342

Comments

Black adolescents who lived in poverty and were less optimistic about the future showed accelerated aging in their immune cells and were more likely to have elevated insulin resistance between ages 25 and 29, the researchers found.

Allen W. Barton, professor of human development and family studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, is first author of the study, which tracked the health of 342 African Americans over 20 years, from their teens to their mid-to-late twenties.

The researchers’ goal was to explore links between individuals’ childhood social environment and insulin resistance , a precursor to diabetes in which cells do not respond to insulin or use blood glucose for energy. Participants lived in rural Georgia, a region with one of the highest poverty rates and shortest life expectancy in the US.

"Once we found some compelling evidence that family poverty during childhood was associated with participants’ insulin resistance in their late 20s, we looked at aging immune cells as a possible mediator, something that transmits the effect." ”Barton said. “And we found support for that. "Aging of immune cells was one pathway, a mechanism through which poverty was associated with insulin resistance."

The findings, published in the journal Child Development , support the hypothesis that chronic diseases, such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome, which occur at significantly higher rates among black adults and low-income populations, may partially originate with experiences much earlier in life, even during childhood, and that such disadvantages can influence the cognition and physiology of individuals.

“Understanding these health disparities associated with race and socioeconomic status really requires a developmental perspective, but prospective research with these populations is scarce,” Barton said.

“In addition to focusing on contemporary stressors , such as their socioeconomic status in adulthood, where they currently live, and their access to health care, prospective studies like this one that follow participants into adulthood are important to explore pathways.” development that originate in childhood to see associations between individuals’ early social environment and their later health outcomes as adults," he said.

Recent research cited in the current study also indicates that type 2 diabetes and other diseases are affecting certain populations, especially blacks, at much younger ages.

The data used in the new study was obtained from the Strong Black Families Healthy Adults Project, also called SHAPE, which enrolled 667 black fifth-grade students and their caregivers. SHAPE began collecting data in 2001.

Young adults in the sample provided at least one blood sample at age 20 and again between ages 25 and 29. From these samples, the researchers assessed the biological age of the participants using DNA methylation and compared this age to their chronological age. Participants’ blood samples were also used to quantify their insulin resistance levels at ages 25, 27, and 29.

At six time points, beginning when the children were 11 years old and continuing through age 18 , caregivers completed questionnaires about their family’s need-to-income ratio , which were used to calculate their poverty status and the number of years they lived. below the federal poverty level.

Three times between ages 16 and 18, youth completed the Perceived Life Opportunities Scale , a 10-item inventory that asked whether they believed they would go to college or get a well-paying job, and how likely that was.

In their initial analyses, the researchers found that living in poverty between ages 11 and 18 was associated with insulin resistance between ages 25 and 29. The longer participants lived in poverty during adolescence, the greater their risk of insulin resistance and diabetes in adulthood, the researchers found. This risk was calculated using a Homeostatic Model of Insulin Resistance, or HOMA, score. Each additional year of poverty was associated with a HOMA score higher than more than one point.

When the children were between 19 and 20 years old, the researchers examined DNA methylation in a subset of participants. DNA methylation is a natural process associated with aging that can affect gene function.

When the researchers also considered whether adolescents believed they could achieve their goals as adults, they found that spending more years living in poverty was associated with fewer perceived life opportunities . The team found associations between young people’s perceived life chances and premature aging of immune cells in their 20s, which was then linked to insulin resistance, Barton said.

“We don’t know what might have happened to them before age 11, so maybe things were implemented that we can’t evaluate yet,” Barton said of the study’s limitations.

Researchers continue to follow individuals in the sample and are exploring the role of resilience in participants’ health outcomes as they age, he said.

“It’s a tremendous data set and can begin to answer some important public health questions, shed light on some of these racial disparities and help find ways to mitigate them,” Barton said.

Psychosocial mechanisms

Previous research highlights the ways in which exposure to persistent and repetitive poverty-related stressors affects youth’s cognitive orientations in areas that have implications for mental and behavioral health. However, corresponding attention to the association between these cognitive orientations and the biological processes involved in disease is rare, despite some evidence that beliefs , particularly about the future, predict health outcomes. For example, decreased purpose in life, fatalistic tendencies, and a negative future orientation have been associated with increased allostatic load . Informed by this literature, the current study considered the possibility that perceptions of fewer life opportunities, a cognitive orientation more common among disadvantaged children, would operate as a mediator linking family poverty to cellular aging.

Discussion

Poverty and other contextual stressors endemic to the rural southern United States have long been theorized as contributing factors to racial health disparities. Prospective research investigating this proposed association is extremely scarce, particularly with disadvantaged populations.

Using a sample of rural African American youth and parents followed for nearly two decades , the current study addressed this gap by providing some of the first empirical evidence to document (a) the possible association between childhood poverty and insulin resistance in later life. young adulthood, and (b) the psychosocial and biological mechanisms that contribute to this association. Findings provide support for life course perspectives on health and the developmental origins of chronic diseases

| In summary , our findings suggest that youth exposure to family poverty during adolescence is associated with higher levels of insulin resistance (IR) in young adulthood, with perceived life chances and cellular aging mediating this association. . The study incorporated multiple strengths, including having nearly two decades of data from an understudied high-risk population, as well as data collection that occurred across multiple informants and multiple levels (e.g., self-report, blood draw intravenous). The current findings underscore the value of a developmental perspective for understanding the emergence of chronic diseases. |

Co-authors of the study include research scientist Tianyi Yu and Gene H. Brody, founder and co-director of the Family Research Center, both at the University of Georgia; psychology professors Edith Chen and Gregory E. Miller, who co-direct the Health Foundations Research Center at Northwestern University; and Qiujie Gong, a predoctoral fellow at the U. of I.