Highlights Patients who recover from coronavirus infection suffer higher rates of neurological and psychological problems, according to a large observational study published in The Lancet Psychiatry . Researchers at the University of Oxford reviewed more than a million patient records and found that two years after infection, patients who had recovered from COVID-19 had a higher risk of psychosis, dementia and "brain fog." compared to patients who recovered from COVID-19. other respiratory diseases. For some symptoms, there was an initial spike that later stabilized. Anxiety and depression fell to rates consistent with other respiratory illnesses after two months. But in the case of brain fog , for example, adults between the ages of 18 and 64 who had recovered from COVID-19 suffered from it at a rate 16 percent higher than patients with other respiratory illnesses. The difference was more marked in those over 65 years of age, where a higher risk of psychosis and dementia was also found . |

Background

COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of neurological and psychiatric sequelae in the weeks and months that follow. It is still unclear how long these risks remain, whether they affect children and adults similarly, and whether SARS-CoV-2 variants differ in their risk profiles.

Methods

In this analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies, we extracted data from the TriNetX electronic health records network, an international network of de-identified health care record data of approximately 89 million patients collected from hospital, primary care, and healthcare providers. specialists. (mainly from the US, but also from Australia, the UK, Spain, Bulgaria, India, Malaysia and Taiwan).

A cohort of patients of any age with COVID-19 diagnosed between January 20, 2020 and April 13, 2022 was identified and propensity score matched (1:1) to a contemporary cohort of patients with any other infection. respiratory. Matching was performed based on demographic factors, risk factors for COVID-19 and severe COVID-19 disease, and vaccination status.

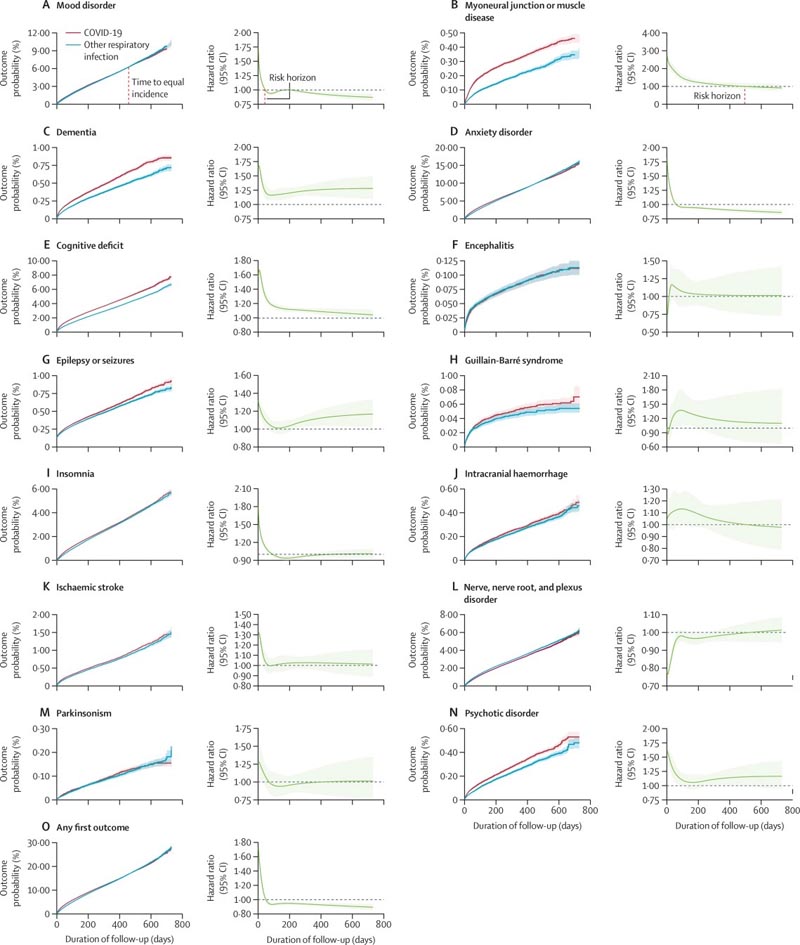

Analyzes were stratified by age group (age <18 years [children], 18–64 years [adults], and ≥65 years [older adults]) and date of diagnosis. We assessed the risks of 14 neurological and psychiatric diagnoses after SARS-CoV-2 infection and compared these risks with the matched comparison cohort. 2-year risk trajectories were represented by time-varying hazard ratios (HRs) and summarized using constant 6-month HRs (representing risks in the earlier phase of follow-up, which have not yet been well characterized in children), the risk horizon for each outcome (i.e., the time at which the HR returns to 1), and the time to equal incidence in the two cohorts.

We also estimated how many people died after a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis during follow-up in each age group. Finally, we compared matched cohorts of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 directly before and after the emergence of the alpha (B.1.1.7), delta (B.1.617.2), and omicron (B.1.1.529) variants.

Results

We identified 1,487,712 patients with a recorded diagnosis of COVID-19 during the study period, of which 1,284,437 (185,748 children, 856,588 adults, and 242,101 older adults; overall mean age 42·5 years [SD 21·9 ]; 741 806 [57·8%] were women and 542 192 [42·2%] were men) were appropriately matched with the same number of patients with another respiratory infection.

Risk trajectories of outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection across the entire cohort differed substantially. While most outcomes had HRs significantly greater than 1 after 6 months (with the exception of encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, disorders of the nerves, nerve roots and plexuses, and parkinsonism), Their risk horizons and time to equal incidence varied greatly.

Risks for common psychiatric disorders returned to baseline after 1 to 2 months (mood disorders at 43 days, anxiety disorders at 58 days) and subsequently reached an overall incidence equal to that of the comparison group paired (mood disorders at 457 days, anxiety disorders at 417 days). days).

In contrast, the risks of cognitive deficits (known as brain fog ), dementia, psychotic disorders, and epilepsy or seizures were still increasing at the end of the 2-year follow-up period.

Post-COVID-19 risk trajectories differed in children compared to adults: in the 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, children were not at increased risk for mood changes (HR 1· 02 [95% CI 0·94–1·10) or anxiety disorders (1·00 [0·94–1·06]), but had a higher risk of cognitive deficits, insomnia, intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, disorders of the nerves, nerve roots and plexuses, psychotic disorders, and epilepsy or seizures (HRs ranging from 1·20 [1·09–1·33] to 2·16 [1·46–3·19]).

Unlike adults, cognitive deficit in children had a finite risk horizon (75 days) and a finite time to equal incidence (491 days). A considerable proportion of older adults who received a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis, in either cohort, subsequently died, especially those diagnosed with dementia, epilepsy, or seizures.

Risk profiles were similar just before and just after the emergence of the alpha variant (n=47,675 in each cohort). Just after (vs. just before) the emergence of the delta variant (n=44,835 in each cohort), increased risks of ischemic stroke, epilepsy or seizures, cognitive deficits, insomnia, and anxiety disorders were observed, compounded by higher mortality rate. With omicron (n=39,845 in each cohort), there was a lower mortality rate than just before the emergence of the variant, but the risks of neurological and psychiatric outcomes remained similar.

Kaplan-Meier curves and time-varying HRs over the 2-year follow-up period for each outcome (AN) and any first outcome (O) after COVID-19 or another respiratory infection in the propensity-score matched cohorts.

Interpretation

This analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies of people diagnosed with COVID-19 showed that the increased incidence of mood and anxiety disorders was transient, with no overall excess of these diagnoses compared to other respiratory infections. In contrast, the increased risk of psychotic disorder, cognitive deficits, dementia, and epilepsy or seizures persisted throughout treatment. The different trajectories suggest a different pathogenesis for these outcomes.

Children have a more benign overall psychiatric risk profile than adults and older adults, but their sustained increased risk for some diagnoses is cause for concern. The fact that neurological and psychiatric outcomes were similar during the delta and Omicron waves indicates that the burden on the health system could continue even with variants that are less severe in other respects.

Our findings are relevant to understanding the risks of neurological and psychiatric disorders at individual and population levels following SARS-CoV-2 infection and may help inform our responses to them.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study with a comparison cohort that evaluates the risks of a variety of neurological and psychiatric outcomes of COVID-19 up to 2 years after the index SARS-CoV-2 infection. We found that the risks of post-COVID neurological and psychiatric outcomes follow different trajectories : the risk of cognitive deficits, dementia, psychotic disorder, and epilepsy or seizures remains elevated 2 years after SARS-CoV-2 infection, while Risks for other diagnoses (particularly mood and anxiety disorders) disappear after 1 to 2 months and do not show an overall excess during 2 years of follow-up.

We also found that risk trajectories differ somewhat in children: they are not at increased risk for mood or anxiety disorders (even during the first 6 months) and their risk for cognitive deficits is transient, but they share the risk for adults of various other diagnoses. and have a notable risk of epilepsy or seizures. Finally, we found that the risks of neurological and psychiatric outcomes remain similar after the emergence of the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) as with the delta variant (B.1.617.2), but are offset by a lower mortality rate. significantly lower.

Implications of all available evidence

The persistent increased risk of cognitive deficits, dementia, psychotic disorders, and post-COVID-19 epilepsy or seizures 2 years after the index infection calls for improved service delivery to diagnose and manage these sequelae, and research to understand the mechanisms.

The different profile of post-COVID-19 neurological and psychiatric diagnoses in children informs the risk-benefit association of policies aimed at preventing COVID-19 in pediatric populations and suggests that the underlying mechanisms could be, in part, different from those of adults.

The observation of comparable neurological and psychiatric risks just after (compared to just before) the emergence of the Omicron variant suggests a continued neuropsychiatric burden of COVID-19 even with variants leading to less severe disease.