| 1. Introduction |

Low muscle mass and malnutrition affect the health and well-being of many people, especially older adults and patients with acute and chronic illnesses. Therefore, early detection and intervention are essential to counteract the detrimental effects of these conditions.

The advent of body composition assessment has allowed researchers to define important characteristics and consequences of low muscle mass. Since low musculature and malnutrition are often hidden in patients with normal weight or in those with excess adiposity, these conditions are frequently overlooked; therefore, such techniques are of significant value.

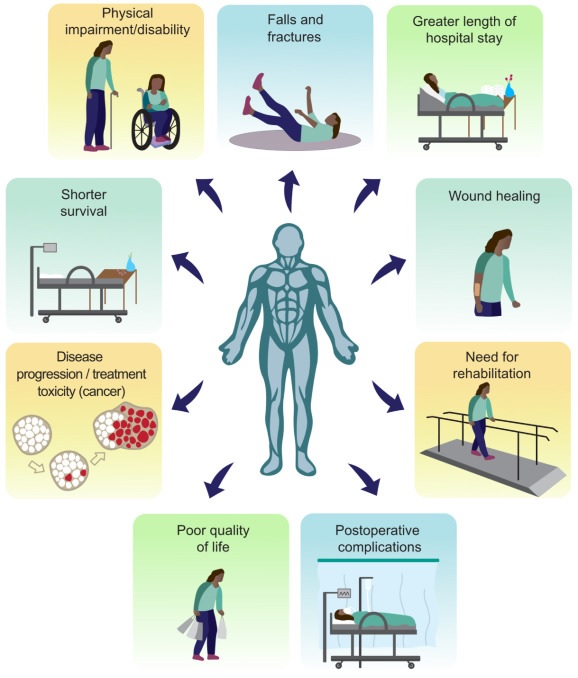

It is also important to note that low muscle mass and malnutrition are associated with impaired immune function and are predictors of adverse clinical situations (e.g., physical disability, falls and fractures, increased length of hospital stay).

This article reports on the 119th Annual Global Research Conference on Key Topics in Pediatric and Adult Nutrition held in June 2021. The objective of this edition was to bring together international experts to provide healthcare professionals with a summary of the latest Advances in research on muscle mass and malnutrition in the contexts of aging and disease.

Figure: Selected consequences of low muscle mass (or related conditions, such as sarcopenia, frailty, and cachexia) and malnutrition in clinical and aging populations. There is a large body of research reporting on associations between low muscle mass and physical impairment or disability, falls and fractures, increased length of hospital stay, wound healing, need for rehabilitation, increased risk of postoperative complications, poor quality of life. , tumor progression, increased treatment toxicity and reduced survival.

| 2 . Towards a better understanding of low muscle mass and malnutrition as overlapping conditions |

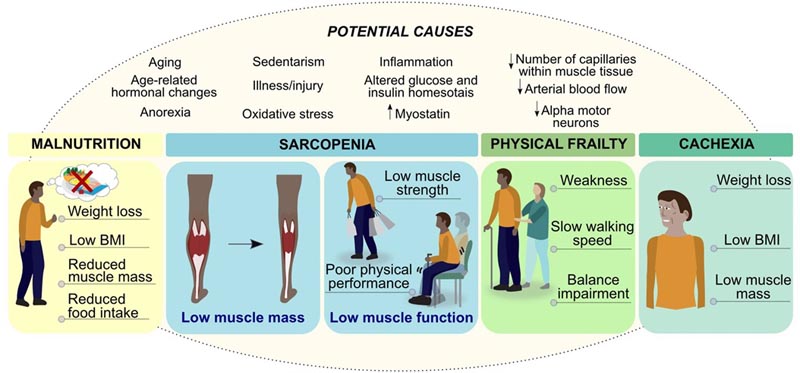

Malnutrition and muscle-related conditions (i.e., low muscle mass, myosteatosis [or fatty infiltration of muscle tissue], sarcopenia, cachexia, and frailty) should not be viewed as isolated entities but as conditions that may occur simultaneously or sequentially in some individuals Most patients with malnutrition have low muscle mass or sarcopenia, but this is not an exclusive condition. Likewise, not all patients with low muscle mass are malnourished. Malnutrition is often a precursor to sarcopenia, as it leads to reduced physical function and unfavorable changes in body composition.

Although low muscle mass and malnutrition can occur independently, they often overlap, especially among hospitalized patients and those with chronic diseases such as cancer.

Figure: Interaction between malnutrition, sarcopenia, physical frailty and cachexia. Malnutrition is one of the factors that can lead to loss of muscle mass and function (i.e. sarcopenia), which can progress to physical frailty, with negative health outcomes such as mobility and disability. Conversely, malnutrition and low muscle mass can progress to cachexia in people with chronic diseases, such as cancer. Because excess adiposity can mask underlying malnutrition and/or low muscle mass, detailed assessments are essential for early identification of at-risk patients and targeted interventions.

| 3. Emerging evidence on the pathophysiology of low muscle mass |

Low muscle mass is common among older adults as a consequence of the aging process and can be exacerbated in patients of any age with chronic illnesses, acute illnesses, or injuries.

Since low muscle mass is a common component of malnutrition, sarcopenia, and cachexia, it is important to understand its pathophysiology to advance diagnosis and treatment. Immobility and catabolic conditions induce muscle loss when protein degradation pathways are activated: the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which degrades most myofibrillar proteins; and the autophagy-lysosome system, which bulk degrades cellular components and organelles in the cytoplasm (e.g., mitochondria).

Although the pathophysiology of muscle atrophy is not completely understood, the factors that contribute to muscle catabolism have been the subject of considerable research studies in recent decades. These include abnormalities in muscle proteostasis, i.e., fasting/feeding and disuse regulation of muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and muscle protein breakdown (DPM), glucose and insulin homeostasis, inflammation, microvascular and/or neuromuscular function. .

Mitochondrial dysfunction is increasingly recognized as an important metabolic regulator. In the context of aging, several mitochondrial processes in skeletal muscle are impaired, including mitochondrial bioenergetics, as well as mitochondrial synthesis and breakdown (“mitophagy”).

A recent study demonstrated that reduced mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity in muscle was the main factor distinguishing the presence of sarcopenia in older adults. Mitochondrial dysfunction also exists in other acute and chronic conditions, such as cancer and sepsis.

Rapid muscle wasting in critical illness may also be due in part to inflammation-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, with altered metabolism causing protein catabolism and suppression of lipid metabolism and thus myosteatosis. With myosteatosis, blood flow to the muscle is reduced, leading to metabolic dysfunction, including insulin resistance, inflammation, and loss of muscle mass and function.

3.1. Exchange of information between the muscle and the immune system

The interrelationship between skeletal muscle and the immune system is also an emerging topic. In fact, muscle is no longer considered a passive target of the immune system, but rather an active player that regulates both innate and adaptive responses.

Three main mechanisms of interaction between skeletal muscle and immune cells have been discussed, including myokine release, expression of cell surface molecules, and cell-cell interaction.

| 4. Who is at risk for malnutrition and muscle loss? |

> 4.1. Aging

After the third decade of life, people experience approximately 3%-5% decline in skeletal muscle per decade. An important factor contributing to malnutrition and loss of muscle mass is anorexia of aging, a common term to describe the involuntary decrease in nutrient intake at older ages.

> 4.2. Chronic diseases

It has been shown that between 11% and 54% of patients with chronic kidney disease are malnourished while the prevalence of sarcopenia ranges between 4% and 42%. Among cancer patients, approximately 40% may have low muscle mass and, on average, 70% are malnourished.

> 4.3. Critical illnesses

During the first week of hospitalization in the intensive care unit (ICU) sonographically evaluated patients showed early and rapid muscle loss, which is quantitatively more substantial in severely ill patients. Myosteatosis associated with mortality, assessed on admission by computed tomography (CT), should also be considered.

Regarding malnutrition, between 38% and 78% of critically ill patients are malnourished, which is independently associated with poor clinical outcomes.

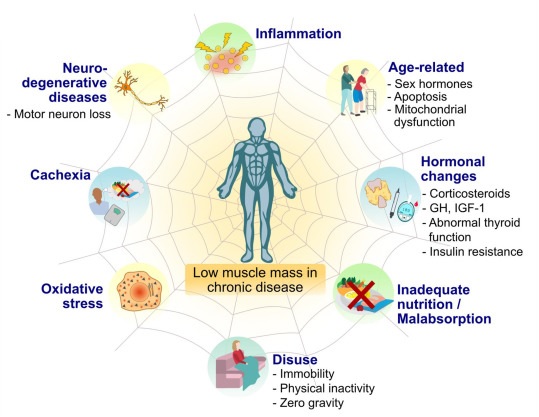

Figure: Selected risk factors contributing to low muscle mass in people with chronic diseases. Abnormalities in muscle mass may arise if at least one of these factors is present; However, multiple risk factors in chronic diseases can lead to severely low muscle mass. Abbreviation: GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1.

> 4.4 COVID-19

As a new disease, COVID-19 has amplified the relevance of low muscle mass like never before; The loss is serious and can have long-term consequences.

Preliminary results from a systematic review on the clinical impact of abnormal body composition in COVID-19 show that low muscle mass is a strong predictor of mortality, hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, disease severity, and ICU admission.

Malnutrition is also very common in COVID-19 patients, with up to 80% of hospitalized patients at risk of malnutrition or malnourished.

Another factor that possibly contributes to malnutrition and loss of muscle mass in these patients is hypermetabolism. A recent study has shown that resting energy expenditure increased in critically ill patients with COVID-19 from week 1 to week 3 of mechanical ventilation and was maintained until week 7; suggesting specific caloric needs during the ICU stay, particularly in non-obese patients.

| 5. Identify patients at risk |

> 5.1. Advances in the evaluation of malnutrition

The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) published a set of evidence-based, clinically relevant criteria to be used in conjunction with comprehensive nutritional assessment or validated assessment tools, such as the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA). for its acronym in English), to diagnose malnutrition in adults in any health care setting.

Practical approaches are suggested for the phenotypic criteria of low muscle mass (non-voluntary weight loss, low BMI, and reduced muscle mass).

> 5.2. Advances in the evaluation of low muscle mass

BMI is not an indicator of muscle health and therefore is not an appropriate indicator of body composition. Several body composition techniques are available to measure or estimate muscle mass. Each technique has its own advantages, limitations and factors that must be taken into account. Some of these factors include validity, feasibility, safety, and practicality (including patient comfort and environmental considerations).

The overall performance of commonly used methods may differ between research and clinical (inpatient and outpatient) settings.

> 5.2.1 Bioelectrical impedance and phase angle analysis

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) estimates muscle mass using population, equation, and device-specific prediction equations; these can be potential sources of error when used on individual patients.

An alternative approach is to use phase angle (APh), an AIB value derived from resistance and reactance measurements, which is becoming an emerging marker of abnormal body composition. Phase angle is an indicator of cell membrane health and integrity and has been used as a prognostic indicator in a variety of conditions, such as survival in cancer patients.

Evidence suggests that APh correlates with muscle area, muscle composition, and is associated with an increased risk of dysmobility syndrome, which is defined by a score consisting of six components (osteoporosis, low lean mass, history of falls, slow walking speed, low grip strength and high fat mass).

> 5.2.2. Ultrasound

With the availability of portable measurement devices, ultrasound (US) is a promising tool for the evaluation of muscle mass in clinical practice.

Reference literature shows that upper arm and upper thigh thicknesses assessed by ultrasound correlated well with muscle area measurements by CT scans, suggesting it is a suitable, radiation-free alternative.

> 5.2.3. CT images

The use of CT data to assess body composition has greatly expanded our understanding of the relationship between muscle mass and tolerance to cancer treatment, complications, and survival, particularly in oncology. However, separation of adipose and muscle tissues on CT has historically relied on manual segmentation, which is labor-intensive, time-consuming and subject to variability.

Several software programs are now available for automated CT segmentation, with data showing strong agreement between automated and manual analysis.

Another important parameter is muscle radiodensity, a marker of muscle composition of increasing prognostic value. In patients with colorectal cancer, low preoperative muscle radiodensity was associated with increased length of postoperative hospital stay, complication rates, and mortality.

> 5.2.4. Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

It is an expensive but useful technique since it measures three body compartments and emits low doses of radiation. Clinically it is recommended for the evaluation of fat mass but its validity for evaluating lean soft tissue is still unknown.

> 5.2.5. Deuterated creatine dilution

Deuterated creatine (CrD3) is a new measure of functional muscle mass. It is determined from a single-point urine collection to estimate muscle mass, that is, the size of the creatine store.

Despite being an indirect measurement of muscle mass, the method is precise, non-invasive and safe. However, this analysis is based on the use of high-performance liquid chromatography, a sophisticated analysis that limits its use in clinical practice.

> 5.2.6. Alternative Approaches to Assessing Muscle Mass

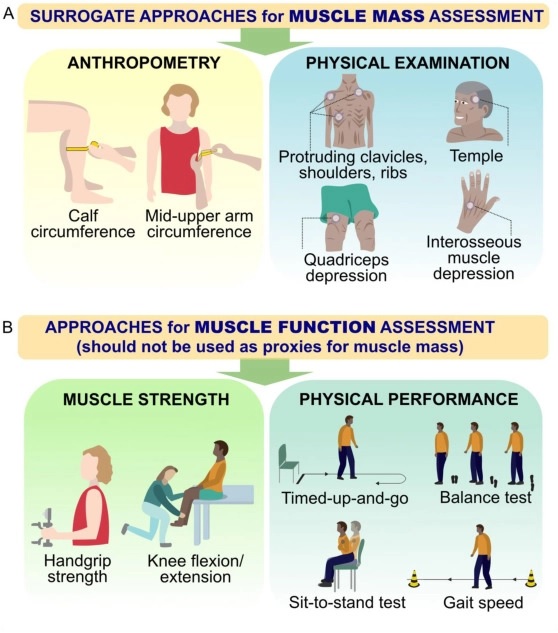

When body composition techniques are not available, alternative approaches can be used, including physical examination to detect overt muscle loss and anthropometry (e.g., mid-arm circumference and calf circumference).

Figure: Alternative approaches to muscle mass assessment in clinical practice when valid body composition techniques are not available. A) Approaches include anthropometric measurements (i.e., calf circumference, upper arm circumference) and a visual examination of muscle loss in specific parts of the body (i.e., collarbones, shoulders, ribs, temples, thighs and hands). B) Approaches to assessing muscle function should not be used as surrogate measures of muscle mass.

| 6. Can we prevent or reverse muscle loss and malnutrition with nutritional interventions? |

Nutrition is essential to support muscle anabolism, reduce catabolism and improve outcomes in patients with muscle loss and malnutrition. Furthermore, nutritional interventions are most beneficial when they are proactive, started early, and continued throughout recovery, preferably as part of multimodal interventions that also include exercise.

Because achieving nutritional intake goals in older adults and clinical populations can be challenging, individualized nutritional counseling should be offered along with nutritional therapy, as supported by care guidelines.

> 6.1. Proteins and amino acids

Proteins and amino acids support muscles by providing substrates for SPM and the immune system by converting pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into the anti-inflammatory form, M2. The ability of dietary proteins to stimulate SPM depends mainly on their essential amino acid (EAA) content and the rate of protein digestion.

Muscle has an intrinsic ability to recognize when it has ingested enough amino acids in a given period to replace those lost during periods of intermittent fasting.

Compared to plant sources of protein, animal proteins have higher digestibility and provide the EAAs necessary for SPM (including higher leucine content). Consequently, studies have shown a greater anabolic effect of animal-based protein on SPM than plant-based proteins both under resting conditions and after exercise.

> 6.2. Branched Chain Amino Acids: Focus on Leucine

Compared to other EAAs, leucine is perhaps the most potent anabolic. Feed healthy young men with 3 grams. of leucine per day is associated with a pronounced increase in SPM, even in the absence of other amino acids, suggesting a recognition system for leucine as a marker of protein intake.

Despite these findings, supplementation with leucine or branched-chain amino acids alone may not stimulate maximal SPM response as they lack other EAAs.

> 6.3. ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (HMB)

It is a bioactive anabolic metabolite of leucine that is synthesized in muscle and found in small amounts in the diet. When consumed orally, HMB exerts anabolic effects on SPM similar to those of leucine. Surprisingly, HBM supplementation has been shown to suppress DPM to a greater extent than leucine.

> 6.4. Vitamin D

It is a fat-soluble vitamin well recognized for its role in bone and muscle health. Research has demonstrated the link between vitamin D deficiency and muscle dysfunction, possibly due to loss of vitamin D receptor function, increased oxidative stress, and impaired mitochondrial function.

There is also evidence of a longitudinal association between low vitamin D status and sarcopenia. Additionally, vitamin D affects immunity and has been shown to regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, increase muscle proliferation, differentiation and growth, and increase natural regulatory T cells involved in modulating the immune response.

> 6.5. n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFA)

Considered a class of fatty acids, n - 3 LCPUFAs exert anti-inflammatory effects that strengthen the interaction between skeletal muscle and immune system cells to promote muscle anabolism.

Evidence shows that the anti-inflammatory effects of n - 3 LCPUFAs reduce cytokine-mediated muscle-specific protein loss and cell death to promote anabolism by inhibiting proteolysis.

Daily supplementation with n - 3 LCPUFA is associated with improved muscle mass and physical performance in healthy older adults.

> 6.6. Polyphenols

Like n - 3 LCPUFAs , polyphenols have anti-inflammatory properties that can modify the crosstalk between muscle and immune cells. However, to date evidence on the effects of polyphenol supplements on muscle health in older adults and clinical populations is limited.

> 6.7. Oral nutritional supplements (ONS)

SONs contain additional protein, energy, micronutrients and potentially other specialized nutrients or ingredients described above to support muscle health and improve nutritional status.

Numerous studies have shown that ONS supplementation improves energy, protein, and micronutrient intake beyond food alone.

> 6.8. Nutraceuticals

Several nutraceuticals can exert positive effects on anabolism, strength and muscle function. These include creatine, carnitine and b-alanine to improve bioenergetics whether at rest or under exercise conditions, nitrates to improve vascular function and biological phosphatidic and ursolic acids, which have been shown to trigger growth pathways in muscle.

Despite this, further research is required to evaluate these compounds and their effectiveness on muscle health in people with or at risk of muscle loss due to aging, malnutrition or disease.

| 7. Adjunctive exercise interventions |

It is important to recognize the importance of regular exercise, preferably in combination with nutritional interventions, as a multidisciplinary approach throughout the care process.

A systematic review of 37 randomized controlled studies compared the effect of nutrition combined with regular exercise versus exercise alone on muscle mass and function in healthy older adults. Exercise was found to improve muscle mass, strength and physical performance.

A pooled analysis of studies offering protein supplements and/or high-protein diets to older adults revealed that only interventions combining nutrition and resistance exercise benefited appendicular lean soft tissue and grip strength.

| 8. Healthy aging: shifting focus from expecting frailty to living strong |

The healthy aging paradigm should focus on maintaining good health and the ability to develop quality of life for as long as possible. This includes optimizing nutrition and exercise to prevent age-related muscle loss that can lead to frailty, dysmobility syndrome, and loss of independence.

Home-based interventions have been shown to increase the number of days in a month in which physical and mental health are described as generally good.

| 9. Recommendations for clinical practice |

To ensure that at-risk patients are consistently screened, evaluated, treated, and monitored, the following clinical practice recommendations are offered:

- Advanced screening, evaluation and diagnostic practices for low muscle mass and malnutrition - The SARC-F and SARC-CalF tools can be used to detect sarcopenia in older adults. Several validated tools are available to detect the risk of malnutrition, such as the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) and the Nutritional Risk Assessment 2002 (NRS-2002).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased use of telehealth highlighted the relevance and need for digital tools such as R-MAPP (remote malnutrition application) for remote patient screening, assessment and monitoring.

- Use of surrogate tools to identify low muscle mass in the absence of body composition techniques - As not all body composition assessment methods are available in all clinical settings, surrogate markers of muscle mass (e.g. , calf circumference).

- Promote multidisciplinary care - The pathophysiology of muscle loss is multifactorial, as is the need for an approach from several areas to prevent/stop this condition.

- Provide nutritional education for patients, families and caregivers - It is essential to increase awareness of lack of muscle mass and malnutrition and improve patients’ knowledge of the early signs of muscle loss and malnutrition.

| 10. Future research perspectives |

More scientific evidence is needed to understand the benefit of integrating body composition assessment into clinical practice and the impact of using this information to personalize nutritional interventions in the prevention and treatment of low muscle mass and malnutrition.

Specific immunological targets and muscle aspects must be explored, which may transform the understanding and therapeutics of low muscle mass. Additionally, more research is required to explore the impact of nutrition and exercise interventions to maximize anabolic potential, physical performance, and outcomes in healthy aging and acute and chronic diseases, including acute conditions such as COVID-19.

Recommendations have been provided for future nutrition trials to rapidly advance the translation of knowledge of interventions addressing muscles, sarcopenia and cachexia into clinical practice.

| 11. Conclusion |

Clinical practice is changing, and healthcare professionals are encouraged to implement many of the tools discussed here to assess muscle loss and malnutrition in their settings.

Muscle loss and malnutrition can hide in plain sight, but screening is the only means of identifying people at risk. Various nutritional interventions including individual nutrients or ingredients, bioactive ingredients and SNO have been shown to improve muscle mass, composition and function (muscle health) and may be important tools to address structural deficits.

Importantly, combining nutritional interventions with exercise as components of a multidisciplinary approach is an important strategy to improve patient outcomes.