A new study provides experimental evidence that late eating causes decreased energy expenditure, increased hunger, and changes in adipose tissue that, combined, may increase the risk of obesity.

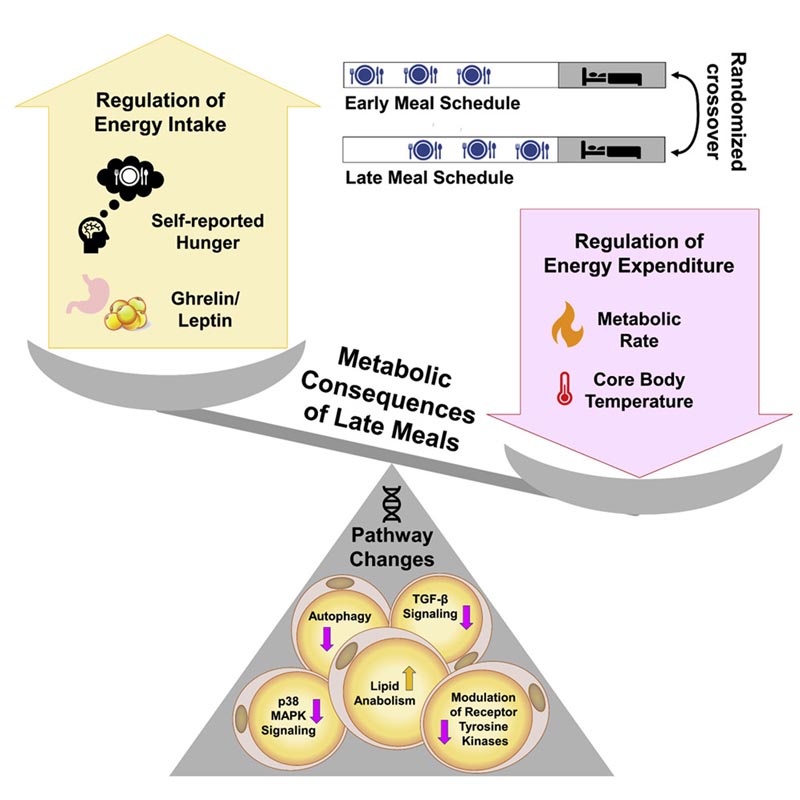

Highlights • Eating late increases hunger upon awakening and decreases 24-hour serum leptin. • Eating late decreases energy expenditure upon awakening and 24-hour core body temperature. • Eating late alters the gene expression of adipose tissue, favoring greater lipid storage. • Combined, these changes in late eating may increase the risk of obesity in humans. |

Summary

Eating late has been linked to the risk of obesity. It is unclear whether this is caused by changes in hunger and appetite, energy expenditure, or both, and whether molecular pathways in adipose tissues are involved. Therefore, we conducted a randomized, controlled, crossover trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02298790) to determine the effects of eating late versus eating early while rigorously controlling nutrient intake, physical activity, sleep, and exposure to light.

Late eating increased hunger (p < 0.0001) and altered appetite-regulating hormones, increasing wake-up time and the 24-hour ghrelin:leptin ratio (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.006, respectively). Additionally, late eating decreased awakening energy expenditure (p = 0.002) and 24-h core body temperature (p = 0.019). Gene expression analyzes of adipose tissue showed that late feeding altered pathways involved in lipid metabolism, e.g., p38 MAPK signaling, TGF-β signaling, modulation of receptor tyrosine kinases, and autophagy, in a direction consistent with decreased lipolysis/increased adipogenesis. These findings show converging mechanisms by which late eating may result in positive energy balance and increased risk of obesity.

Graphic summary

Comments

Obesity affects approximately 42 percent of the U.S. adult population and contributes to chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and other conditions. While popular healthy diet mantras discourage midnight snacking, few studies have comprehensively investigated the simultaneous effects of late eating on the three main factors in regulating body weight and therefore obesity risk: regulation of calorie intake, the amount of calories you burn and the molecular changes in fatty tissue.

A new study by researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, found that when we eat significantly affects our energy expenditure, appetite, and molecular pathways in adipose tissue. Their results are published in Cell Metabolism .

"We wanted to test mechanisms that may explain why late eating increases the risk of obesity," explained senior author Frank AJL Scheer, PhD, Director of the Medical Chronobiology Program in Brigham’s Division of Circadian and Sleep Disorders. “Previous research by us and others had shown that eating late is associated with a higher risk of obesity, higher body fat, and lower weight loss success. “We wanted to understand why.”

"In this study, we asked, ’Does how long we eat matter when everything else is held constant?’" said first author Nina Vujović, PhD, a researcher in the Medical Chronobiology Program in Brigham’s Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders. . “And we found that eating four hours later makes a significant difference in our hunger levels, the way we burn calories after eating, and the way we store fat.”

Vujović, Scheer and their team studied 16 patients with a body mass index (BMI) in the overweight or obese range. Each participant completed two lab protocols: one with a strictly scheduled early meal time and the other with exactly the same meals, each scheduled about four hours later in the day.

In the last two to three weeks before starting each of the protocols in the laboratory, participants maintained fixed sleep-wake schedules, and in the last three days before entering the laboratory, they strictly followed identical diets and meal schedules in home.

In the lab, participants regularly documented their hunger and appetite, provided frequent small blood samples throughout the day, and had their body temperature and energy expenditure measured. To measure how timing of eating affected the molecular pathways involved in adipogenesis, or how the body stores fat, the researchers collected biopsies of adipose tissue from a subset of participants during laboratory testing in the early and late eating protocols, to allow comparison of gene expression patterns/levels between these two feeding conditions.

The results revealed that eating later had profound effects on hunger and the appetite-regulating hormones leptin and ghrelin, which influence our drive to eat. Specifically, levels of the hormone leptin, which signals satiety, were reduced over the 24 hours in the late-feeding condition compared to the early-feeding conditions. When participants ate later, they also burned calories at a slower rate and exhibited adipose tissue gene expression toward increased adipogenesis and decreased lipolysis, which promotes fat growth. In particular, these findings convey convergent physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the correlation between late eating and increased risk of obesity.

Vujović explains that these findings are not only consistent with a large body of research suggesting that eating later can increase the likelihood of developing obesity, but they shed new light on how this might occur. By using a randomized crossover study and strict control of environmental and behavioral factors, such as physical activity, posture, sleep, and light exposure, the researchers were able to detect changes in the different control systems involved in energy balance, a marker of how our bodies use the food we eat.

In future studies, Scheer’s team aims to recruit more women to increase the generalizability of their findings to a broader population. While this study cohort included only five female participants, the study was set up to control for menstrual phase, reducing confounding but making it difficult to recruit women. In the future, Scheer and Vujović are also interested in better understanding the effects of the relationship between mealtime and bedtime on energy balance.

“This study shows the impact of eating late versus eating early. Here, we isolate these effects by controlling for confounding variables such as caloric intake, physical activity, sleep, and light exposure, but in real life, many of these factors can be affected by themselves and influenced by the meal times,” Scheer said. “In larger scale studies, where strict control of all these factors is not feasible, we must at least consider how other behavioral and environmental variables alter these biological pathways that underlie obesity risk. ”