In an "emulated" clinical trial , longer work weeks were strongly linked to greater increases in depression symptoms, pushing some first-year medical residents into the moderate or severe depression range

The more hours someone works per week in a stressful job, the more their risk of depression increases, according to a study in new doctors.

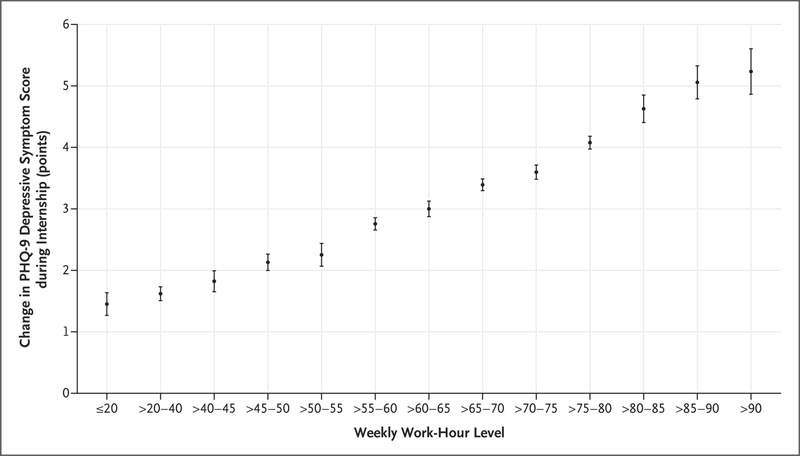

Working 90 hours or more per week was associated with changes in depression symptom scores three times greater than the change in depression symptoms among those working 40 to 45 hours per week.

Additionally, a higher percentage of those who worked a high number of hours had scores high enough to qualify for a diagnosis of moderate to severe depression, severe enough to warrant treatment, compared to those who worked fewer hours.

The research team, based at the University of Michigan, used advanced statistical methods to emulate a randomized clinical trial, taking into account many other factors in the doctors’ personal and professional lives.

They found a "dose response" effect between hours worked and symptoms of depression, with an average increase in symptoms of 1.8 points on a standard scale for those working 40 to 45 hours, with a range of up to 5.2 points for those who worked more than 90 hours. They conclude that, among all the stressors affecting physicians, working long hours is a major contributor to depression.

Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine , the team at Michigan Medicine, UM’s academic medical center, reports their findings from studying 11 years of data on more than 17,000 first-year medical residents . Newly graduated doctors were in training at hundreds of hospitals in the United States.

The data comes from the Intern Health Study, based at the Michigan Neuroscience Institute and the Eisenberg Family Depression Center. Each year, the study recruits new medical school graduates to participate in a year of tracking their depressive symptoms, work hours, sleep, and more as they complete the first year of residency, also called the internship year.

Estimated mean change in PHQ-9 score for depressive symptoms during medical clerkship, based on weekly work hour levels, among 17,082 participants in the Internal Health Study, 2009–2020.

Scores on the 9-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) were assessed at baseline (1 to 2 months before the start of the internship) and then quarterly during the internship year. On the PHQ-9, depression is classified as minimal with a score of 0 to 4, mild with a score of 5 to 9, moderate with a score of 10 to 14, moderately severe with a score of 15 to 19, and severe with a score of 20 to 27. The widths of the 95% confidence intervals (bars) have not been adjusted for multiplicity and cannot be used in place of hypothesis testing. The analysis adjusted for baseline factors of sex, surgical or nonsurgical specialty, personality trait of neuroticism, history of depression before internship, early family environment, age, calendar year of cohort, marital status, parental status and time-varying factors of stressful life events and medical errors.

The impact of a high number of working hours

This study comes as major national organizations, such as the National Academy of Medicine and the Association of American Medical Colleges, grapple with how to address high rates of depression among physicians, physicians in training and other health professionals. Although interns in the study reported a wide range of work hours from the previous week, the most common work hour levels were between 65 and 80 hours per week.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which sets national standards for residency programs, currently sets a limit of 80 hours on residents’ workweeks, but that can be averaged over four weeks and there are possible exceptions. ACGME also limits the length of a single shift and the number of days in a row residents can work. Studies have shown mixed results about the impact these limits have had on resident well-being and patient safety risks.

The authors say their findings point to a clear need to further reduce the number of hours residents work each week on average.

"This analysis strongly suggests that reducing the average number of work hours would make a difference in the degree to which interns’ depressive symptoms increase over time and reduce the number of people who develop diagnosable depression," says Amy Bohnert, Ph. D., the lead author of the study and a professor at the UM School of Medicine. “The key is for people to work fewer hours; “You can deal more effectively with the stress or frustrations of your job when you have more time to recover.”

Yu Fang, MSE, lead author of the study and research specialist at the Michigan Neuroscience Institute, notes that the number of hours is important, but so are the training opportunities that arise from time spent in hospitals and clinics. “It is important to use time spent at work for supervised learning opportunities and not for low-value clinical service tasks,” he says.

A population ripe for study

The new study uses a design called an emulated clinical trial , which simulates a randomized clinical trial in situations where an actual randomized trial is not feasible. Because almost all interns across the country start at about the same time of year and are subject to different work schedules set by their programs, studying people who go through this stage of medical training is ideal for emulating a trial. clinical.

This opportunity is what led Intern Health Study founder Srijan Sen , MD, Ph.D. to launch the research project first: New doctors entering the most stressful year of their careers form a perfect group to study the role of many factors in the risk or onset of depression. The authors suggest that studies parallel to this work in doctors should be conducted in other high-stress, long-hour jobs. “We would expect the negative effect of long work hours on doctors’ mental health to be present in other professions,” Sen says.

The average age of the doctors in the study was 27 years old , and just over half were women. One in five were training in surgical disciplines, and 18% were from racial or ethnic groups traditionally underrepresented in the medical profession.

Less than 1 in 20 met criteria for moderate to severe depression at the beginning of the internship year. In total, 46% had a stressful life event, such as the death or birth of a family member, or getting married, during their internship year, and 37% said they had been involved in at least one medical error during the year .

When analyzing the results, the researchers adjusted for sex, neuroticism, pre-internship history of depression, early family environment, age, year they started the internship, marital status, whether they had children, and stressful events. of life and medical errors during the internship year.

Make a difference for today’s residents

“National initiatives on physician well-being have increasingly placed emphasis on the complex set of factors that affect physician well-being, including electronic health record, regulatory burden, resilience, workplace violence, work and culture,” says Sen, director of EFDC. and the Eisenberg Professor of Depression and Neurosciences. “I think this emphasis has inadvertently led to the feeling that the problem is infinitely complicated and that making real progress is futile. “This paper demonstrates how big an impact the single factor of work hours has on physicians’ depression and well-being.”

Sen is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Task Force on Navigating the Impacts of COVID-19 on Clinician Wellbeing, part of a larger effort that recently issued a National Plan for Health Workforce Wellbeing .

Bohnert notes that residency directors running training programs for new physicians could reduce work hours by prioritizing efforts that increase efficiency and reduce unnecessary work.

Fang also notes that the data from U.S. residents may apply to junior doctors, as they are called, in other nations. The Intern Health Study is now also enrolling interns in China and Kenya.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH101459)