Consumption of ultra-processed foods that contain little or no whole foods in their ingredients contributed to 57,000 premature deaths in Brazil in 2019, researchers report in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Ultra-processed foods (UPF), industrial ready-to-eat or heat formulations made with ingredients extracted from foods or synthesized in laboratories, have gradually replaced traditional foods and meals made with fresh and minimally processed ingredients in many countries. A new study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, published by Elsevier, found that higher consumption of these foods was associated with more than 10% of preventable premature deaths from all causes in Brazil in 2019, although Brazilians consume much less of these products than high-income countries.

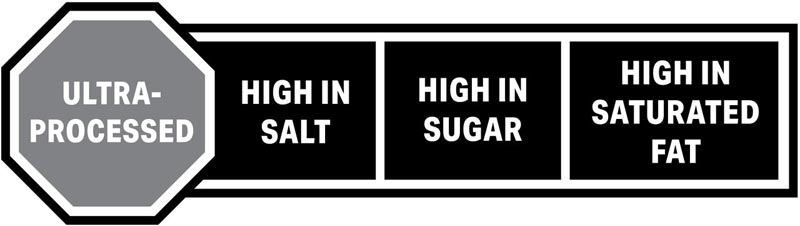

"Previous modeling studies have estimated the economic and health burden of critical ingredients, such as sodium, sugar, and trans fats, and specific foods or beverages, such as sugar-sweetened beverages," explained lead researcher Eduardo AF Nilson, ScD. , Center for Epidemiological Research in Nutrition and Health, University of São Paulo, and Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil. “To our knowledge, no study to date has estimated the potential impact of UPF on premature deaths. “Knowing the deaths attributable to the consumption of these foods and modeling how changes in dietary patterns can support more effective food policies could prevent illness and premature death.”

Dr. Nilson and colleagues modeled data from nationally representative dietary surveys to estimate baseline UPF intake by sex and age group. Statistical analyzes were used to estimate the proportion of total deaths attributable to UPF consumption and the impact of reducing UPF intake by 10%, 20% and 50% within those age groups, using 2019 data.

In all age groups and sex strata, UPF consumption ranged between 13% and 21% of total food intake in Brazil during the period studied. A total of 541,260 adults aged 30 to 69 died prematurely in 2019, of which 261,061 were from preventable non-communicable diseases.

The model found that approximately 57,000 deaths that year could be attributed to UPF consumption, corresponding to 10.5% of all premature deaths and 21.8% of all deaths from preventable non-communicable diseases in adults aged 30 to 69. years. The researchers suggested that in high-income countries such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia, where UPFs account for more than half of total caloric intake, the estimated impact would be even greater.

Dr. Nilson noted that UPFs have steadily replaced the consumption of traditional whole foods, such as rice and beans, over time in Brazil. Reducing UPF consumption and promoting healthier food options may require multiple public health interventions and measures, such as fiscal and regulatory policies, changing food environments, strengthening the implementation of food-based dietary guidelines, and improving knowledge, attitudes and consumer behavior.

Reducing UPF consumption by 10% to 50% could potentially prevent approximately 5,900 to 29,300 premature deaths in Brazil each year.

“UPF consumption is associated with many disease outcomes, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some types of cancer and other diseases, and represents a major cause of premature and preventable deaths among Brazilian adults,” said the Dr. Nilson. “Even reducing UPF consumption to levels just a decade ago would reduce associated premature deaths by 21%. Policies that discourage UPF consumption are urgently needed.”

Having a tool to estimate deaths attributable to UPF consumption can help countries estimate the burden of dietary changes related to industrial food processing and design more effective food policy options to promote healthier food environments.

Examples of UPF are soups, sauces, frozen pizza, ready-to-eat meals, hot dogs, sausages, soft drinks, ice cream and prepackaged cookies, cakes, candies and donuts.