WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

The number of people screened for signs of stroke in US hospitals dropped by nearly 40% during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a study led by researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine. in St. Louis that analyzed stroke evaluations at more than 800 hospitals in 49 states and the District of Columbia.

The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine , are a worrying indication that many people who suffer strokes may not be seeking life-saving medical care.

"Our stroke team has maintained full capacity to provide emergency stroke treatment at all times, even during the height of the pandemic," said senior author Akash Kansagra, MD, assistant professor of radiology at the Institute of Radiology. Mallinckrodt (MIR) from the University of Washington. Kansagra cares for stroke patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. "However, we have seen a smaller number of stroke patients arriving at the hospital and some patients arriving at the hospital after a considerable delay . It is absolutely heartbreaking to meet a patient who could have recovered from a stroke but, for whatever reason, you waited too long to seek treatment."

Nearly 800,000 people in the United States experience a stroke each year. It is the fifth leading cause of death and the leading cause of long-term disability. With advances in stroke care, such as better diagnostic tools, surgeries to remove blood clots or repair broken blood vessels, and blood-thinning medications, people have a better chance of recovering from a stroke today than ever, as long as they receive treatment quickly.

| Blood-thinning medications are generally safe only within 4½ hours of symptom onset, and surgeries are only possible within 24 hours of symptom onset. The sooner treatment is started, the more successful it will be. |

Concerned about the low number of stroke patients being evaluated at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and hearing similar reports from colleagues at other institutions, Kansagra, along with co-authors Manu Goyal, MD, assistant professor of radiology and neurology at the University of Washington, and statistician Scott Hamilton, PhD, and neurologist Gregory Albers, MD, both of Stanford University, set out to determine how widespread the problem was.

When patients arrive at the hospital and show signs of a stroke, they often undergo a brain scan so doctors can identify what type of stroke has occurred and choose the most effective treatment. Many hospitals, including Barnes-Jewish Hospital, use software known as RAPID to analyze such brain scans. Kansagra and his colleagues assessed how frequently the software was used in February, before the pandemic and during a two-week period from March 26 to April 8, when much of the country was under shelter-in-place orders. .

In total, the software was used for 231,753 patients at 856 hospitals representing the District of Columbia and all 50 states except New Hampshire. During February, the software was used for an average of 1.18 patients per day per hospital. During the pandemic period, software usage per hospital averaged 0.72 patients per day, a drop of 39%.

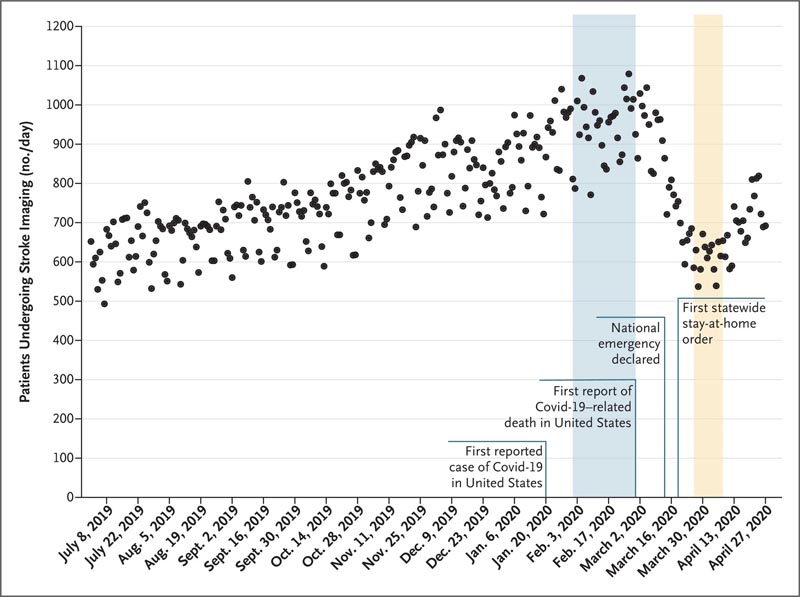

Figure 1. Daily counts of unique patients undergoing neuroimaging for stroke in the United States, July 2019 to April 2020. All neuroimaging tests were processed with RAPID software. Each dot represents a daily patient count. The shaded regions correspond to the pre-pandemic (blue) and early pandemic (yellow) eras. The increase in the number of patients undergoing imaging from July 2019 to March 2020 reflects an increase in the number of hospitals using RAPID software.

Figure 1. Daily counts of unique patients undergoing neuroimaging for stroke in the United States, July 2019 to April 2020. All neuroimaging tests were processed with RAPID software. Each dot represents a daily patient count. The shaded regions correspond to the pre-pandemic (blue) and early pandemic (yellow) eras. The increase in the number of patients undergoing imaging from July 2019 to March 2020 reflects an increase in the number of hospitals using RAPID software.

"Overall, everyone is affected by this decline," said Kansagra, who is also an assistant professor of neurosurgery and neurology. "It’s not just limited to hospitals in urban settings or rural communities, small hospitals or large hospitals. It’s not just the elderly or the young or people with mild strokes who don’t show up. Even patients with very severe strokes are seeking care at cut-rate prices. This is a widespread and very scary phenomenon."

There is no reason to believe that people suddenly stopped having strokes.

The drop was large even in places where COVID-19 cases were few and hospitals were not overwhelmed, so patients should not have found it unusually difficult to get treatment.

"I suspect we are seeing a combination of patients being reluctant to seek care for fear that they may contract COVID-19, and the effects of social distancing," Kansagra said. "The response of family and friends is really important when a loved one is experiencing stroke symptoms. Often, patients themselves are not in a position to call 911, but family and friends recognize stroke symptoms and do so. "The call. In a time when we are all isolating at home, patients who have strokes may not be discovered quickly enough."

Common signs of a stroke include the sudden onset of numbness or weakness in the face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body; difficulty speaking; confusion; difficulty seeing or walking; and severe headache.

Even during a pandemic, it is extremely important that people who may be experiencing a stroke receive care immediately, Kansagra said.

The risk of delaying care for a stroke is much greater than the risk of contracting COVID-19.

"The effect of arriving too late is the same in many ways as not entering at all," Kansagra said. "When patients arrive too late, they may no longer be candidates for treatments they would have qualified for only a few hours earlier. And as a result, they may not have access to treatments that are extremely effective in reducing death and disability." .