Breastfeeding confers multiple health benefits to mothers and babies, and both the American Academy of Pediatrics and Healthy People 2030 have set increasing breastfeeding as a public health goal. Healthy People 2030 reports that about three-quarters of women do not meet the recommendation of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months.

Although nearly 80% of women in the United States initiate breastfeeding, the number of mothers meeting breastfeeding recommendations at 6 months drops to 25%. Among mothers who stop breastfeeding early, low milk production is one of the most frequently cited reasons.

In the United States, ~40% of women of reproductive age (20 to 39 years) are obese . Breastfeeding mothers with obesity are at increased risk of poor breastfeeding outcomes. Insulin resistance and other markers of poorer metabolic health are associated with delayed lactogenesis and low milk production. It is often difficult to disentangle the physiological mechanisms that affect lactation from the effects of behavioral differences in lactation that may covary with obesity or associated conditions. The physiological mechanisms and potential treatments of low milk production in humans are poorly studied.

Obesity is a cause of chronic low-grade inflammation , leading to a marked elevation of acute phase proteins and inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α. Elevated plasma TG is a marker of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome , resulting in part from suppression of LPL expression in adipose tissue by inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. However, it is unknown how inflammation and obesity may alter breast lipid metabolism in lactating mothers.

The transfer of fatty acids from blood to milk is disrupted in mothers with low milk production, obesity and inflammation Summary Background Obesity is associated with chronic inflammation and is a risk factor for insufficient milk production. Inflammation-mediated suppression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) could inhibit mammary absorption of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA; >16 carbons). Goals In an ancillary case-control analysis, we investigated whether women with low milk production despite regular breast emptying have elevated inflammation and disrupted LCFA transfer from plasma to milk. Methods Data and samples from a low milk supply study and an exclusive breastfeeding control group were analyzed, with milk production measured by 24-h test weighing between 2 and 10 weeks postpartum. Low milk supply groups were defined as very low (VL; <300 mL/d; n = 23) or moderate milk production (MOD; ≥300 mL/d; n = 20), and were compared with controls ( ≥699 mL/d; n = 18). Fatty acids in serum and milk (wt% of total) were measured by GC, TNF-α in serum and milk by ELISA, and serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) by clinical analyzer. Group differences were assessed using linear regression models, chi-square exact tests, and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. Results VL cases, compared with MOD cases and controls, had a higher prevalence of elevated serum hsCRP (>5 mg/L; 57%, 15%, and 22%, respectively; P = 0.004), TNF-α in detectable milk (67%, 32%, and 33%, respectively; P = 0.04) and obesity (78%, 40%, and 22%, respectively; P = 0.003). VL cases had lower mean ± SD milk LCFA (60% ± 3%) than MOD cases (65% ± 4%) and controls (66% ± 5%) (P < 0.001). Milk and whey LCFAs were strongly correlated in controls (r = 0.82, P < 0.001), but not in the MOD (r = 0.25, P = 0.30) or VL (r = 0.001) groups. 20, P = 0.41) (Pint < 0.001). Conclusions Mothers with very low milk production have significantly higher inflammatory and obesity biomarkers, lower milk LCFAs, and a disrupted association between plasma and milk LCFAs. These data support the hypothesis that inflammation disrupts normal fatty acid absorption from the mammary glands. Additional research should address the impacts of inflammation and obesity on mammary fatty acid absorption for milk production. |

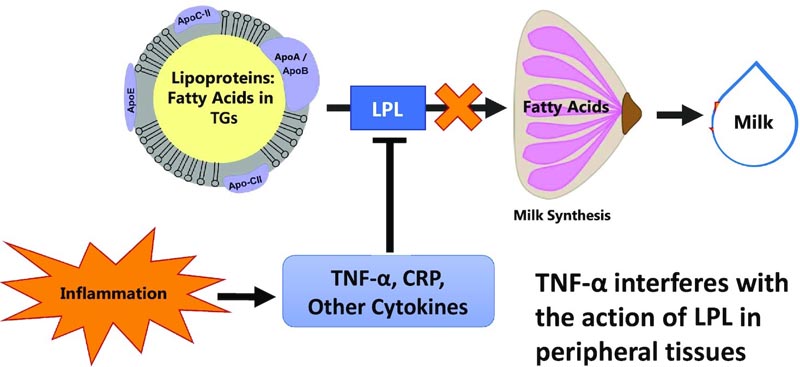

Figure: Hypothetical model for reduced milk production as a result of inflammation-mediated suppression of mammary LPL. Our working model used to construct the hypotheses in this project was that inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α suppress mammary LPL, leading to fewer fatty acids being available to the mammary gland. This would be reflected in lower concentrations of LCFAs (>16 carbons) in milk, because almost all LCFAs in milk are derived from circulation through LPL. Additionally, there are fewer LCFAs available to the mammary gland for energy production, which reduces the rate of milk synthesis. LCFA, long chain fatty acid.

Comments

Eighty percent of mothers breastfeed their newborns, but only 25% breastfeed exclusively for the six months recommended by the United States Dietary Guidelines, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research has shown that many factors contribute to this decline in breastfeeding, including work pressures and lack of social support. However, physical problems producing enough milk are cited as one of the most common reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding earlier than planned. A new study by researchers at Penn State and the University of Cincinnati showed that inflammation in breastfeeding mothers with obesity may contribute to low milk production.

Researchers found that obesity is a risk factor for insufficient milk production in nursing mothers. In people with obesity, chronic inflammation begins in the body’s fat and spreads through the circulation to organs and systems throughout the body, according to the research team. Previous research showed that inflammation can disrupt the absorption of fatty acids from the blood into body tissues.

Fatty acids are essential for creating and accessing the energy needed throughout the body. In lactating women, fatty acids serve as the building blocks of fats needed to feed a growing baby. The researchers hypothesized that inflammation may have a negative impact on milk production by preventing the absorption of fatty acids in the milk-producing mammary glands.

To test this hypothesis, Rachel Walker, a postdoctoral fellow in nutritional sciences at Penn State, led a team of researchers who looked at whether inflammation impeded the absorption of fatty acids. Researchers analyzed blood and milk from a study conducted at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and the University of Cincinnati. In the original study, researchers recruited 23 mothers who had very low milk production despite frequent emptying of the breasts (which is standard medical practice to increase milk production), 20 mothers with moderate milk production and 18 mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding and serving as a parent. control group for the study. In the current study, the researchers analyzed fatty acid profiles and inflammatory markers in both blood and breast milk. Their results were published in The Journal of Nutrition .

Compared with those in the moderate milk production and exclusive breastfeeding groups, mothers with very low milk production had significantly higher obesity and biological markers of systemic inflammation. They also had lower proportions of long-chain fatty acids in breast milk and a disrupted association between blood and milk fatty acids. Milk and blood fatty acids were strongly correlated in controls, but not in very low or moderate milk production groups.

“Science has repeatedly shown that there is a strong connection between the fatty acids you eat and the fatty acids in your blood,” Walker said. “If someone eats a lot of salmon, they will find more Omega-3 in their blood. If another person eats a lot of hamburgers, he will find more saturated fat in his blood.

“Our study was one of the first to examine whether fatty acids in the blood are also found in breast milk,” Walker continued. “For women who exclusively breastfed, the correlation was very high; Most of the fatty acids that appeared in the blood were also present in breast milk. But for women who had chronic inflammation and struggled with milk production, that correlation almost completely disappeared. “This is strong evidence that fatty acids cannot enter the mammary gland in women with chronic inflammation.”

For decades, research has shown that mothers with obesity are at greater risk of shortening the duration of breastfeeding.

This study provides clues to the mechanisms that may explain this result.

"Breastfeeding has countless benefits for both mother and child, including a lower risk of chronic diseases for the mother and a lower risk of infections for the baby," said Alison Gernand, associate professor of nutritional sciences at Penn State, Walker’s postdoctoral mentor and co-author of this research. "This research helps us understand what might be happening in mothers with high weight and inflammation, which in the future could lead to interventions or treatments that allow more mothers who want to breastfeed to do so."

Walker is mentored by Laurie Nommsen-Rivers, associate professor of nutrition and Ruth Rosevear Chair in Maternal and Child Nutrition at the University of Cincinnati, who is also a co-author of the paper. Kevin Harvatine, professor of nutritional physiology at Penn State; A. Catharine Ross, professor emeritus of nutritional sciences at Penn State; Erin Wagner, research associate at the University of Cincinnati College of Allied Health Sciences; and Sarah Riddle, assistant professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the United States Department of Agriculture, as well as by the Dorothy Foehr Huck Endowment at Penn State.