Summary Research shows that phthalates , a class of chemicals associated with plastics, can leach from plastic wrappers, containers, and even gloves worn by food handlers. Once consumed during pregnancy, the chemicals can reach the bloodstream, through the placenta, and then into the fetal bloodstream. The researchers noted that this chemical can cause oxidative stress and an inflammatory cascade within the fetus . Previous literature has indicated that exposure to phthalates during pregnancy may increase the risk of low birth weight, premature birth, and childhood mental health conditions such as autism and ADHD. |

Comments

If you’re pregnant, you might want to think twice before eating a burger or buying a packaged pastry, according to research published last month in the journal Environmental International .

Oddly enough, it’s not the food that the report addresses (not fries, not burgers, not even shakes and cakes), but rather what the food touches before eating it.

Research shows that phthalates, a class of chemicals associated with plastics, can leach from plastic wrappers, containers, and even gloves worn by food handlers. Once consumed during pregnancy, the chemicals can reach the bloodstream, through the placenta, and then into the fetal bloodstream.

The researchers noted that the chemical can cause oxidative stress and an inflammatory cascade within the fetus. Previous literature has indicated that exposure to phthalates during pregnancy may increase the risk of low birth weight, premature birth, and childhood mental health disorders such as autism and ADHD.

This is the first study in pregnant women to show that diets high in ultra-processed foods are linked to increased exposure to phthalates, the authors wrote.

"When moms are exposed to this chemical, it can cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation," said lead author Dr. Sheela Sathyanarayana, a pediatrician at the University of Washington Medicine and a researcher at the Children’s Research Institute. Seattle.

This analysis involved data from the Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Early Childhood Learning (CANDLE) research cohort, which comprised 1,031 pregnant people in Memphis, Tennessee, who enrolled between 2006 and 2011. Phthalate levels were measured in urine samples collected during the second trimester of pregnancy.

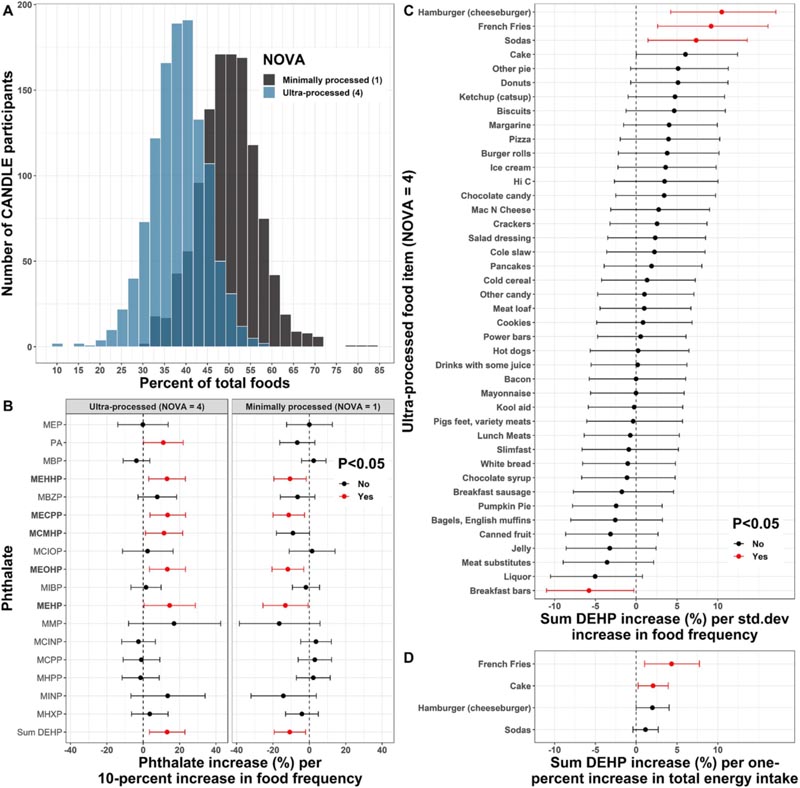

The researchers found that ultra-processed foods made up between 10% and 60% of participants’ diets, or 38.6%, on average. Each 10% higher dietary proportion of ultra-processed foods was associated with a 13% higher concentration of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, one of the most common and harmful phthalates. The amounts of phthalate were obtained through urine samples taken from the women in the study.

Figure: Associations of NOVA groups and ultra-processed foods with phthalate levels. Histogram (A) shows the distribution of CANDLE participants with respect to food frequency for the ultra-processed and minimally processed food groups as a percentage of total food frequency. Linear model coefficients and 95% confidence intervals represent: (B) Associations of dietary proportions of ultra-processed and minimally processed NOVA food group with phthalates from separate models for each NOVA group by combination of phthalate results ; (C) Associations of individual ultraprocessed foods with molar sum of DEHP from separate models per food; and (D) A sensitivity analysis for the top four ultra-processed foods associated with DEHP addition where foods were modeled as a percentage of total daily energy intake rather than frequency of intake. All models in BD were adjusted for maternal age, education, race, ethnicity, household income, number of people in household, neighborhood deprivation index, prepregnancy BMI, consumption of tobacco and alcohol and daily caloric intake.

Ultra-processed foods, according to researchers, are made primarily from substances extracted from foods such as oils, sugar and starch, but have changed so much due to processing and the addition of chemicals and preservatives to improve their appearance or shelf life that they are difficult to recognize from its original form, the researchers noted. These include, for example, packaged cake or chip mixes, hamburger buns and packaged soft drinks.

When it comes to fast food, gloves worn by employees and storage, preparation and serving equipment or tools can be the main sources of exposure. Both fresh and frozen ingredients would be subject to these sources, said lead author Brennan Baker, a postdoctoral researcher in Sathyanarayana’s lab.

According to the researchers, this is the first study to identify ultra-processed foods as a link between phthalate exposure and the socioeconomic problems faced by mothers. Mothers’ vulnerability could be due to financial difficulties and living in "food deserts," where fresh, healthy food is harder to obtain and transportation to distant markets is unrealistic.

"We don’t blame the pregnant person here," Baker said. "We need to call on manufacturers and policymakers to offer replacements, and those that aren’t may be even more harmful."

More legislation is needed, the authors said, to prevent phthalate contamination in food, regulating the composition of food packaging or even the gloves that food handlers can wear.

What should pregnant women do now?

Sathyanarayana said pregnant women should try to avoid ultra-processed foods as much as they can and look for lean fruits, vegetables and meats. Label reading can come into play here, she added.

"Look for the fewest ingredients and make sure you can understand them," he said. This even applies to "health foods" like breakfast bars. See if it’s sweetened with dates or contains a litany of fats and sugars, she said.

Final message In summary, our study demonstrates associations between maternal dietary patterns, particularly consumption of ultra-processed foods and fast food , and higher urinary phthalate concentrations during pregnancy. These findings extend previous research conducted in the general population of the US and Taiwan and highlight dietary sources of phthalates in pregnant women rather than the general population. Additionally, our exploratory factor analysis approach provides data-driven internal validation of the associations between processed food intake and increased phthalate exposure. Additionally, we corroborate the findings of previous studies by showing associations of healthy diets rich in vegetables, fruits, yogurt, fish, and nuts with lower levels of some phthalates. Although these findings have important implications for modifiable lifestyle factors related to dietary choices during pregnancy, unpredictable pollution and socioeconomic barriers to dietary modification preclude the use of dietary recommendations as the only means to reduce exposure to phthalates. Policy reforms are urgently needed to reduce exposure to phthalates in the diet, especially in food packaging. |

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (UG3UH3OD023271).