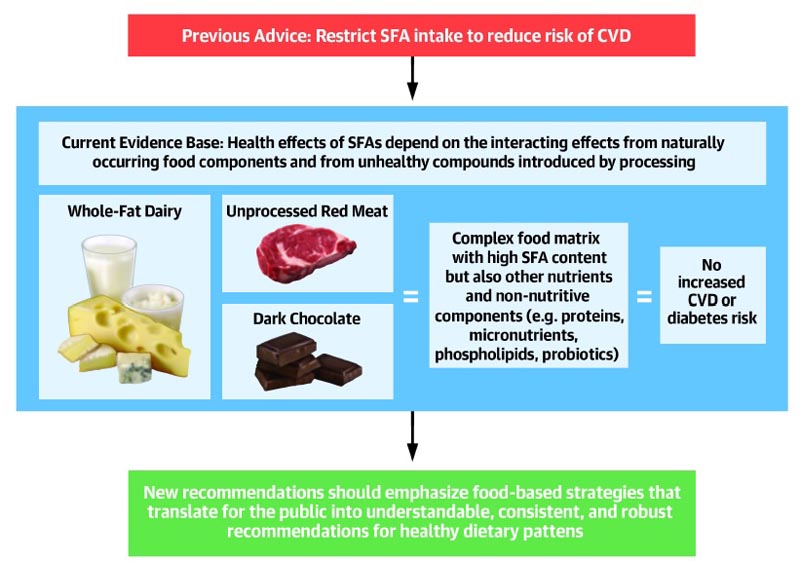

Summary: The recommendation to limit dietary saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake has persisted despite growing evidence to the contrary. More recent meta-analyses of randomized trials and observational studies found no beneficial effects of reducing SFA intake on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and total mortality, and instead found protective effects against stroke. Although SFAs increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, in most individuals, this is not due to increased levels of small, dense LDL particles, but rather to larger LDLs that are much less related to the risk of CVD. It is also evident that the health effects of foods cannot be predicted by their content in any nutrient group, without considering the overall distribution of macronutrients. Full-fat dairy, unprocessed meat, eggs, and dark chocolate are SFA-rich foods with a complex matrix that are not associated with increased CVD risk. The totality of available evidence does not support further limiting the intake of such foods. |

Reducing saturated fat consumption has been a central theme of US dietary goals and recommendations since the late 1970s. Since 1980, it has been recommended that saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake be limited to less of 10% of total calories as a means to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

In 2018, the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services requested public comments in response to the following question: "What is the relationship between saturated fat consumption (types and amounts) and the risk of CVD?" in adults?"

This review aims to address this important question by examining the available evidence on the effects of saturated fat on health outcomes, risk factors, and potential mechanisms underlying cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes, which will have implications for Dietary Guidelines. 2020 for Americans.

The relationship between dietary SFAs and heart disease has been studied in more than 75,000 people and is summarized in a series of systematic reviews of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Some meta-analyses find no evidence that reducing saturated fat consumption can reduce CVD incidence or mortality, while others report a significant, although slight, beneficial effect .

Therefore, the basis for consistently recommending a diet low in saturated fat is unclear . The purpose of this review is to critically evaluate the health effects of dietary SFAs and propose an evidence-based recommendation for healthy intake of different SFA food sources.

Evidence on the health effects of saturated fats

In the 1950s, with the rise of coronary heart disease (CHD) in Western countries, nutrition and health research has focused on a number of "diet-heart" hypotheses . These included the supposed harmful effects of dietary fats (particularly saturated fats) and the lower risk associated with the Mediterranean diet to explain why people in the United States, northern Europe, and the United Kingdom were more likely to have the CHD. In contrast, those in European countries around the Mediterranean had a lower risk. These ideas were fueled by ecological studies such as the Seven Countries Study.

However, in recent decades, diets have changed substantially in several regions of the world. For example, the very high intake of saturated fat in Finland has decreased considerably, with per capita butter consumption declining from ~16 kg/year in 1955 to ~3 kg/year in 2005, and the percentage of energy from saturated fat decreased from ~20% in 1982 to ~12% in 2007 (28). Therefore, dietary guidelines that were developed based on information from several decades ago may no longer be applicable.

Recently, in a large and more diverse study addressing this question, the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study in 135,000 people mostly without CVD from 18 countries on five continents (80% from low- and middle-income countries), Increased consumption of all types of fats (saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated) was associated with a lower risk of death and had a neutral association with CVD. In contrast, a high-carbohydrate diet was associated with an increased risk of death, but not with CVD risk.

This study also showed that people in the quintile with the highest saturated fat intake (approximately ~14% of total daily calories) had a lower risk of stroke , consistent with the results of meta-analyses of previous cohort studies. Furthermore, in a recently published study of 195,658 UK Biobank participants who were followed for 10.6 years, there was no evidence that saturated fat intake was associated with incident CVD.

In contrast, substitution of polyunsaturated saturated fats was associated with an increased risk of CVD . While there was also a positive relationship of saturated fat intake with all-cause mortality, this became significant only with intakes well above average consumption.

In particular, the diet with the lowest risk ratio for all-cause mortality comprised intakes high in fiber (10-30 g/day), protein (14-30%), and monounsaturated fats (10-25%) and fats. moderate polyunsaturated (5). % to <7%) and starch intakes (20% to <30%).

For dietary carbohydrates , as also shown in the PURE study, higher consumption (mainly of starchy and sugary carbohydrates) was associated with increased risk of CVD and mortality . In the context of contemporary diets, therefore, these observations would suggest that there is little need to further limit total or saturated fat intake for most populations.

| In contrast, restricting carbohydrate intake, particularly refined carbohydrates, may be more relevant today to decrease the risk of mortality in some people, for example, those with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. |

Modulation of the health effects of saturated fat by dietary carbohydrate intake and insulin resistance

Insulin-resistant conditions such as metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes affect more than 100 million people in the United States. Insulin resistance manifests functionally as carbohydrate intolerance . For example, lean insulin-resistant subjects show impaired glucose oxidation in skeletal muscle, increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis, and atherogenic dyslipidemia after a high-carbohydrate meal.

Therefore, an individual with insulin resistance has a higher propensity to convert carbohydrates to fat, which will further exacerbate the insulin-resistant phenotype. In addition to standard risk factors (e.g., high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol concentrations, increased central adiposity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia), this phenotype also includes increased circulating levels of SFAs and lipogenic fatty acids, such as palmitoleic acid.

It is important to distinguish between dietary saturated fat and circulating SFA . While several reports show no association between increased SFA intake and risk of chronic disease, individuals with higher circulating levels of even-chain SFAs (particularly palmitate, C16:0) are at increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome. , diabetes, CVD, heart failure and mortality.

Notably, however, the amount of SFA circulating in the blood is not related to dietary saturated fat intake, but instead tends to track more closely with dietary carbohydrate intake.

For example, a 2- to 3-fold increase in saturated fat consumption has no effect or decreases serum SFA levels in the context of lower carbohydrate intake. The decreased accumulation of circulating SFA in response to low-carbohydrate, high-saturated-fat diets is partially mediated by decreased production (via de novo lipogenesis ), but also by increased clearance.

Low-carbohydrate diets consistently increase fat oxidation rates throughout the body, including the preferred use of SFAs as fuel. Therefore, the combination of increased fat oxidation and attenuation of hepatic lipogenesis could explain why higher dietary saturated fat intake is associated with lower circulating SFA in the context of low carbohydrate intake.

Conclusions

The long-standing bias against foods high in saturated fat must be replaced in order to recommend diets consisting of healthy foods.

What steps could change the bias?

We suggest the following measures:

1) Improve public understanding that many foods (e.g., full-fat dairy) that play an important role in meeting dietary and nutritional recommendations may also be high in saturated fat.

2) Let the public know that low-carbohydrate, high-saturated-fat diets , which are popular for managing body weight, may also improve metabolic disease endpoints in some people, but emphasize that the health effects of Carbohydrates in the diet, like saturated fats, will depend on the quantity, type and quality of carbohydrates, food sources, degree of processing, etc.

3) Shift focus from the current paradigm that emphasizes the saturated fat content of foods as key to health, to one that focuses on specific traditional foods , so that nutritionists, dietitians, and the public can easily identify healthy sources of saturated fats.

4) Encourage committees in charge of making macronutrient-based recommendations to translate those recommendations into appropriate and culturally sensitive dietary patterns adapted to different populations.

Highlights

|