Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease, where more than 90% of patients are women. Symptoms vary widely, from mild skin manifestations to life-threatening organ failure.

Although the prognosis since the introduction of corticosteroids and other treatment modalities has improved considerably, there is still increased mortality in SLE with complications, especially in the case of lupus nephritis and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The evolution of diagnostic criteria for SLE is interesting in itself, and the most recent were from the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology in 2019, where positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were required as an entry criterion and then a combination of clinical manifestations and serological/immunological measures.

It should be noted that rheumatic diseases in general are based on criteria , which reflects that knowledge of their causes is relatively scarce, although the directly causing mechanisms are much more defined. It is likely that these criteria will change in the future, and also that the boundaries between these diseases, especially systemic autoimmune diseases (SAD), will not be as clear as the criteria suggest.

The presence of ANA as a prerequisite for diagnosis illustrates that nuclear material (with dead cells as the probable origin) and autoimmunity against it is a central feature of the disease. The abnormal and/or dysfunctional clearance of dead cells represents another important aspect. An imbalance in the immune system with a lower proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) is another peculiarity of SLE and an example of immunological aberration.

SLE is relatively rare. Its incidence is increasing in several countries but this can be attributed to better diagnosis. There are also interesting differences between ethnicities, where SLE is reported to be most common in African and Arab populations, lower among Hispanic and Asian populations, and even lower among Caucasians.

SLE had a much worse prognosis before treatment with immunosuppressants, including cortisone, was instituted. After that, it became clear that CVD was important as a later complication and in a major study from the late 1970s, a bimodal pattern of SLE was reported, where the most acute complications at an early stage of the disease were often followed by CVD at a later stage.

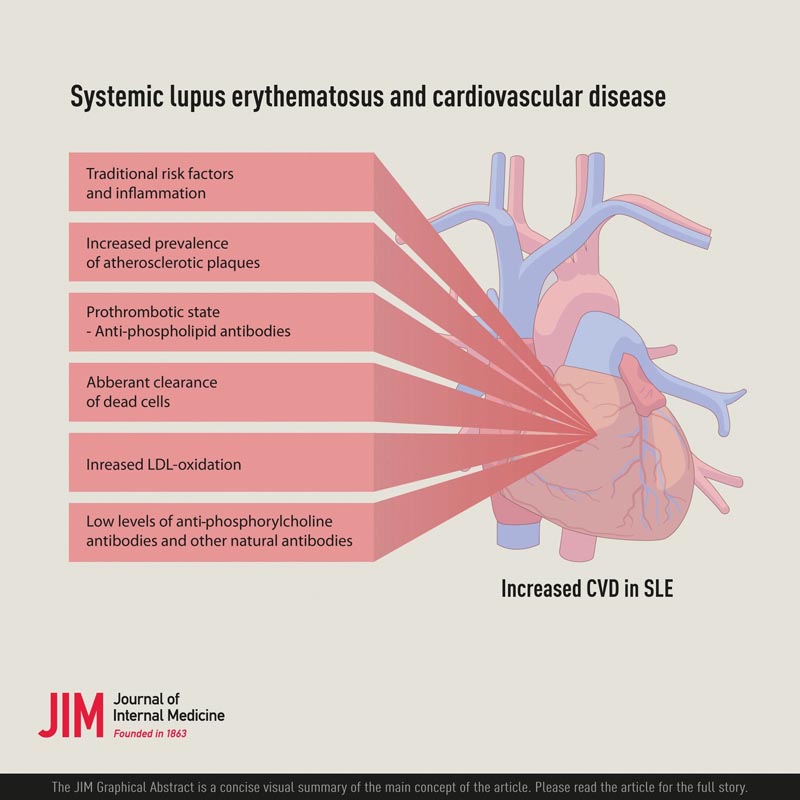

An important question, given the increased risk of CVD in SLE, is what risk factors are involved. A controlled study reported that a combination of traditional and non-traditional risk factors were involved . Among the non-traditional ones, increased levels of oxidized low-density lipoproteins (OxLDL) and also lupus anticoagulants, which are related to antiphospholipid antibodies, were observed. Among the traditional ones, dyslipidemia was associated with CVD. However, dyslipidemia in SLE has specific characteristics, with low high-density lipoproteins (HDL), elevated triglycerides, but not elevated LDL.

The underlying cause of CVD in SLE may be related to both thrombosis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) caused by antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and atherosclerotic disease , which is not yet mutually exclusive.

In general, APS is characterized by thrombosis, both arterial and venous, and by pregnancy complications, especially spontaneous abortion.

SAF is divided into primary and secondary , where the former is rare, although aFL per se can be determined in 1%-5% of the population, rarely leading to SAF. Determination of aPL is also important in other systemic autoimmune diseases, not only in SLE, to reduce the risk of secondary APS.

Antiphospholipid antibodies recognize phospholipids, especially cardiolipin (CL), and it has become clear that phospholipid binding proteins play an important role, with beta-2-glycoprotein I currently considered the most relevant as a cofactor for aPL. Most likely, the pathogenic effects can be divided into two, which are not mutually exclusive: direct effects on the endothelium and other cells and platelets, and interference with the coagulation system leading to a prothrombotic state.

Effects on the coagulation system could play an important role in SLE-related CVD through different mechanisms. Furthermore, there are several possibilities here that are not mutually exclusive. A specific mechanism of how aPL can cause CVD such as stroke and myocardial infarction in SLE is related to annexin A5 , a protein known to bind phosphatidylserine, which is exposed on dead and dying cells and which functions as a template danger-associated molecular (DAMP).

The inflammatory nature of atherosclerosis has been known for a long time. SLE could promote atherosclerosis and/or atherosclerotic plaques.

At the same time, atherosclerosis is a slowly developing inflammatory process in the arteries. It is characterized by the accumulation of dead cells, OxLDL, and activated infiltrate of immunocompetent cells, including T cells, monocytes/macrophages, and also smooth muscle cells, but not much of granulocytes, which are typically a major component in arthritis as in rheumatoid arthritis.

T cells and monocytes/macrophages show signs of activations and produce cytokines, mainly pro-inflammatory such as interleukin 1, 6 and TNF-alpha and accumulate near lesions and damaged parts of plaques. Calcification is also an important feature of atherosclerosis and is most likely a phenomenon related to prolonged inflammation. The exact type of immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory effect are therefore essential in the treatment of CVD with the aim of improving plaque inflammation.

Interestingly, the accumulation of dead cells in atherosclerotic plaques is a hallmark of this disease, which could be described as dysfunctional clearance of dead cells. Furthermore, OxLDL is a relevant factor in atherosclerosis and, like dead cells, accumulates in plaques and increases in SLE.

Since the determination that T cells are present in atherosclerotic plaques and also actively produce mainly proinflammatory cytokines, their functional role in the development of CVD has been widely studied and discussed. Although much remains to be known about the role of IL-17 and the corresponding Th17 cells and also other proinflammatory T cell subsets, they appear to be primarily proatherogenic.

An imbalance in the immune system with a lower proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) is another characteristic of SLE and an example of immune calibration. Tregs are important for the suppression of autoimmune reactions against oneself .

Regulatory T cells ( Tregs) can suppress pro-inflammatory effects and also have other interesting properties that could improve atherosclerosis, such as inhibition of foam cell formation and induction of anti-inflammatory macrophages.

A therapeutic option in autoimmune disease, especially in SLE, may be to increase the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs), to restore balance with effector T cells. Options include Treg-activating compounds such as low-dose interleukin-2.

The underlying cause of the low proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in SLE is unclear, but may be related to the cytokine environment, which promotes cellular decline. There are also other interesting possibilities in relation to both atherosclerosis and SLE, including OxLDL and so-called natural antibodies, especially anti-PC and the plasma protein annexin A5.

Since oxidation remains a common denominator, the term OxLDL is commonly used. OxLDL has been in the spotlight as a culprit in atherosclerosis since at least the late 1980s. It is taken up by macrophages , which become inert foam cells in atherosclerotic lesions, where they eventually die and become part of a necrotic core. OxLDL promotes cell death and has pro-inflammatory and immunostimulatory properties.

Another non-mutually exclusive cause of the proinflammatory effects and immune activation by OxLDL is phosphorylcholine (PC), which in previous studies was reported to play a role in OxLDL-induced immune activation and the production of the major proinflammatory cytokine IFNgamma. .

CVD is, therefore, a considerable cause of morbidity and mortality in SLE, and is caused by a combination of factors with prothrombotic and/or atherogenic properties. Traditional risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, should be reduced by established therapies in general CVD prevention. Positive data have recently been published on the use of statins, both in hyperlipidemia and APS in SLE.

Another important question is what role corticosteroid treatment plays in SLE-related CVD. There are associations between high doses of corticosteroids and CVD in SLE, but on the other hand, these patients are the ones who present the most severe manifestations and, again, it is important to optimize therapy so that the most acute manifestations of the disease are treated as best as possible.

Hydroxychloroquine is a cornerstone in the treatment of SLE and, interestingly, also has a role in the prevention of CVD . In a recent meta-analysis, hydroxychloroquine was shown to reduce the risk of thromboembolic events by 49%.

The risk of CVD is high in SLE and is caused by both an increased risk of thrombosis and increased atherosclerosis, especially atherosclerotic plaques.

This represents an important clinical problem, but could also shed light on the inflammatory and immunological nature of atherosclerosis. A combination of traditional and non-traditional risk factors, including those related to SLE as disease activity, appear to explain this increased risk. For the prevention and treatment of CVD in SLE, traditional risk factors must be addressed and therapeutic resources optimized.