Association between self-reported sleep problems, infection and antibiotic use in patients in general practice Goals: There is emerging evidence that sleep problems and short sleep duration increase the risk of infection. Our objective was to evaluate whether chronic insomnia disorder, chronic sleep problems, sleep duration, and self-reported circadian preference were associated with risk of infections and antibiotic use among patients visiting their general practitioner ( GP). Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study of 1,848 unselected patients in Norway who visited their GP during 2020. Patients completed a one-page questionnaire while waiting for the consultation, which included the validated Bergen Insomnia Scale (BIS), questions that assessed sleep problem, sleep duration and circadian preference and whether they had had any infections or used antibiotics in the last 3 months. Relative risks (RR) were estimated using modified Poisson regression models. Results: The risk of infection was 27% (95% CI RR 1.11–1.46) and 44% higher (95% CI 1.12–1.84) in patients who slept <6 h and >9 h, respectively, compared to those who slept 7–8 hours. The risk also increased in patients with chronic insomnia or a chronic sleep problem. For antibiotic use, the risk was highest for patients who slept less than 6 hours and for those with chronic insomnia or a chronic sleep problem. Conclusions: Among patients visiting their primary care physician, short sleep duration, chronic insomnia, and self-reported chronic sleep problem were associated with a higher prevalence of infection and antibiotic use. These findings support the notion of a strong association between sleep and infection. |

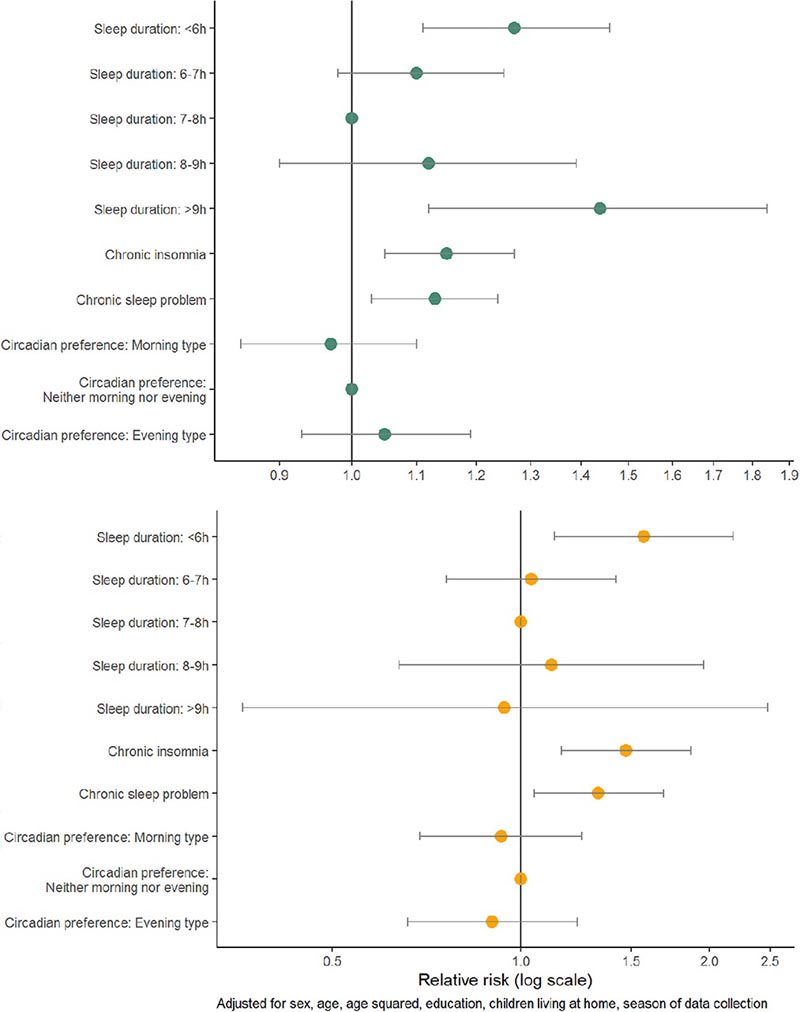

Adjusted relative risks with 95% confidence interval of any type of infection (upper panel) and antibiotic use (lower panel) among 1,848 patients who visited their primary care physicians in spring and fall 2020.

Comments

A good night’s sleep can solve all kinds of problems, but scientists have now discovered new evidence that getting a good night’s sleep can make you less vulnerable to infections . Scientists at the University of Bergen recruited medical students working in doctors’ offices to give short questionnaires to patients, asking them about sleep quality and recent infections. They found that patients who reported getting too little or too much sleep were more likely to also report a recent infection, and patients who experienced chronic sleep problems were more likely to report needing antibiotics.

“Most previous observational studies have looked at the association between sleep and infection in a general population sample,” said Dr. Ingeborg Forthun, corresponding author of the study published in Frontiers in Psychiatry. “We wanted to evaluate this association among primary care patients, where we know that the prevalence of sleep problems is much higher than in the general population.”

Studying sleep in the doctor’s office

There is already evidence that sleep problems increase the risk of infection: in a previous study, people deliberately infected with rhinovirus were less likely to catch a cold if they reported healthy sleep. Sleep disorders are common and treatable, and if a link to infection and mechanism can be confirmed, it may be possible to reduce antibiotic use and protect people against infections before they happen. But experimental studies cannot reproduce real-life circumstances.

Forthun and his colleagues gave the medical students a questionnaire and asked them to hand it out to patients in the waiting rooms of the general practitioners’ surgeries where the students worked. 1,848 surveys were collected throughout Norway. The surveys asked people to describe the quality of their sleep (how long they typically sleep, how well they feel they sleep, and when they prefer to sleep), as well as whether they had had any infections or used any antibiotics in the past three months. The survey also contained a scale that identifies cases of chronic insomnia disorder.

Risk of infection increased by a quarter or more

The scientists found that patients who reported sleeping less than six hours a night were 27% more likely to report an infection, while patients who slept more than nine hours were 44% more likely to report one. Sleeping less than six hours or chronic insomnia also increased the risk of needing an antibiotic to overcome an infection.

"The increased risk of reporting an infection among patients who reported short or long sleep duration is not that surprising, since we know that having an infection can cause poor sleep and drowsiness ," Forthun said. “But the increased risk of infection among those with chronic insomnia disorder indicates that the direction of this relationship also goes in the other direction ; Poor sleep can make you more susceptible to infection .”

Although there was some potential for bias in that people’s recall of sleep or recent health problems is not necessarily perfect, and clinical information was not collected from doctors who later saw the patients, the study design allowed data collection from a large study group experiencing real-world conditions.

"We don’t know why patients visited their GPs, and it could be that an underlying health problem affects both the risk of poor sleep and the risk of infection, but we don’t think this can fully explain our results," Forthun said. .

He continued: “Insomnia is very common among primary care patients, but is not recognized by general practitioners. "There is a need for greater awareness of the importance of sleep, not only for general well-being, but also for patient health, among both patients and general practitioners."

Implications for research and practice

The results of the present study are in line with previous experimental studies in humans that have found an increased risk of infection with sleep deprivation or insomnia . In two studies in which healthy adults were infected with rhinovirus, those who slept little before exposure to the virus were more likely to develop a clinical cold. Similarly, previous studies found a reduction in the number of virus-specific antibody titers for influenza, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and H1N1 (swine flu) in people with sleep problems before and after vaccination.

Poor sleep can affect several immune parameters which, in turn, could reduce the body’s ability to fight an infection.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental and cohort studies on sleep disorders, sleep duration, and inflammation reported an increase in the inflammatory markers C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) with the presence of sleep disorder. defined through the use of validated questionnaires. The same study reported an association between long sleep duration (>8 h) and an increase in CRP and IL-6, while no evidence of an increase in inflammatory markers was found for short sleep.

Less attention has been paid to the effect of sleep disorders, such as insomnia, on the immune response . Insomnia is very common among patients in general practice, but is underrecognized among GPs . Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been found to be highly effective in a primary care setting and there is also evidence to suggest that such treatment can reduce the level of CRP in the blood. Recently, a more direct link between insomnia and infection risk was demonstrated in a Mendelian randomization study using genetic data from a large Finnish cohort.

Unlike experimental studies, we could not exclude the role of potential unobserved confounders . An underlying health problem could affect both the risk of sleep problems and infections. For example, long sleep duration is associated with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, and has also been linked to depression, low education, low levels of physical activity, and high rates of alcohol and tobacco use. Of these, we only had information on educational level.

We consider the results on chronic insomnia disorder to be more robust than the results on sleep duration, as insomnia is a long-term condition that is considered independent of other conditions. Although an underlying health problem could be a possible unobserved causal factor for both sleep problems and infection risk in the present study, it is likely that better sleep could serve as a moderator in reducing infection risk. More longitudinal studies are needed in the general population and among patients in general practice, as well as clinical studies on the effect of insomnia treatment on the risk of infection. Data on different groups of infections and their possible differences in associations with sleep could provide us with important clues about possible underlying mechanisms.