Summary Peripheral artery disease ( PAD) has an enormous social and economic burden and contributes significantly to the global health burden. Sex differences in PAD are evident, with recent data suggesting equal or greater prevalence in women, and that women have worse clinical outcomes. It is not clear why this occurs. To identify the underlying reasons for gender inequalities in EAP, we executed a deeper exploration through a social constructive perspective. A scoping review was conducted using the World Health Organization model for gender-related needs analysis in healthcare. Complex interacting factors, including biological, clinical, and social variables, were reviewed to highlight gender-related inequalities in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of PAD. Current gaps in knowledge were identified and ideas on future directions aimed at improving these inequalities were discussed. Our findings highlight the multi-level complexities that must be considered for strategies to improve gender-related needs in PAD healthcare. |

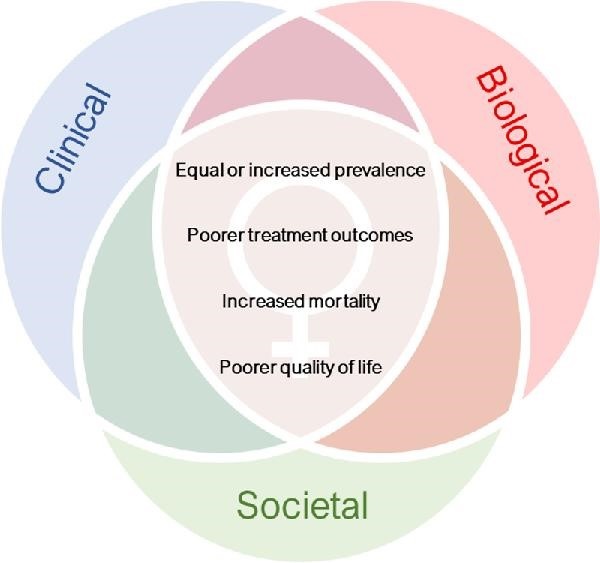

Figure : Biological, clinical, and social interactions that impact health-related inequalities in women with peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Comments

Treatments for peripheral artery disease (PAD) were largely developed in men and are less effective in women, according to a review published in European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcome s, a journal of the European Society of Cardiology ( ESC). The paper highlights the biological, clinical and social reasons why the condition may go unrecognized in women, who respond worse to treatment and have worse clinical outcomes.

"More understanding is needed about why we are not addressing the health outcomes gap between genders," said author Mary Kavurma, associate professor at the Australian Heart Research Institute. “This review covers not only biological reasons, but also how healthcare services and the role of women in society may play a role. “All of these elements must be taken into account so that the most effective diagnostic and treatment methods can target women with PAD.”

PAD is the main cause of lower limb amputation.

More than 200 million people worldwide have PAD where the arteries in the legs are blocked, restricting blood flow and increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke. The evidence suggests that an equal or greater number of women have the condition and that they have worse outcomes. This review was carried out to identify the reasons for gender inequalities in EAP. The researchers collected the best available evidence and used the World Health Organization model for analysis of gender-related needs in health care.

The document begins with a summary of gender inequalities in the diagnosis and treatment of PAD. It then describes the biological, clinical, and social variables responsible for these gender-related disparities. Regarding diagnosis , PAD is classified into three phases: asymptomatic, typical symptoms of pain and cramps in the legs when walking that are relieved with rest (intermittent claudication) and chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) which is the stage more severe and may include gangrene or ulcers.

Women often have no symptoms or atypical symptoms, such as mild pain or discomfort when walking or resting.

They are less likely than men to have intermittent claudication and twice as likely to have CLTI. Hormones appear to play a role, as women tend to show typical symptoms (intermittent claudication) after menopause. The ankle-brachial index, which compares blood pressure in the upper and lower extremities, is used for diagnosis, but is less accurate in people without symptoms or with smaller calf muscles.

Treatment of PAD includes medication, exercise, and surgery. It aims to control symptoms and reduce the risks of ulceration, amputation, heart attack and stroke. Women are less likely to receive recommended medications than men and respond less well to supervised exercise therapy. Women have lower rates of surgery and are more likely to die after amputation or open surgery than men.

Regarding the reasons for the aforementioned inequalities, biological factors may contribute to sex differences in disease presentation, progression, and response to treatment. For example, women have a higher risk of blood clots (a cause of PAD) and smaller blood vessels, while oral contraceptives and pregnancy complications have been linked to higher rates of PAD.

Clinical factors refer to how patients interact with healthcare services, their relationships with physicians, and the processes established to diagnose and treat PAD. The paper cites low awareness of the risk of PAD in women among healthcare providers and women themselves. Healthcare personnel are less likely to recognize PAD in women than in men, and women are more likely than men to be misdiagnosed for other conditions, including musculoskeletal disorders.

Women tend to downplay their symptoms and are less likely to talk about PAD with their doctor.

Over the past 10 years, only one-third of participants in PAD treatment clinical trials were women. One reason may be that the inclusion criteria require the presence of intermittent claudication, which is less common in women.

The review identified a number of social variables that may contribute to gender inequalities in PAD. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with a higher likelihood of PAD and hospitalization for PAD. Furthermore, the incidence of PAD is higher in low- and middle-income countries and increases more rapidly in women. The authors note that women have a lower socioeconomic position than men in most nations, partly due to reduced income and education levels, and caregiving responsibilities. “The increased poverty and socioeconomic disparities experienced by women around the world may contribute to increased rates of PAD in women,” the paper states.

The authors point out the low proportion of female vascular surgeons and their insufficient representation in leadership roles and on EAP guideline writing teams. Co-author Associate Professor Sarah Aitken, vascular surgeon and head of surgery at the University of Sydney, commented: "While we are working to encourage women to train as vascular surgeons, the current shortfall means female patients are unlikely to go to a surgeon" of the same gender, and research, publications and policies may not fully represent women’s perspectives."

Associate Professor Kavurma urged women not to ignore the symptoms: “Pay attention to aches and pains in your calves when walking or resting. Ask your GP how likely it is that you have PAD. Women tend to follow and attribute leg pain to having a busy life. “They need to stop and listen to their bodies.”

She concluded: “As a vascular biologist, my main research questions about PAD are: Why are women asymptomatic? Is the disease different between men and women, particularly before menopause? And why do women respond worse to treatment? The answers to these questions are essential: How can doctors diagnose and treat patients with PAD without understanding how the disease develops and whether it is different between the sexes? To improve treatments, we also need clinical trials to include women more.”

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has been raising awareness of gender differences in cardiovascular diseases since 2008 with a Women in the ESC campaign. Numerous activities followed, including a focus on women and cardiovascular disease at the ESC Congress 2011. The ESC hosts the only registry of pregnancy and heart disease (ROPAC). In 2022, the ESC Gender Policy was launched, setting targets for the inclusion of women cardiologists and cardiovascular scientists in leadership positions and outlining measures to improve gender equality, including promoting mentorship and career advancement.