Key points Do specific organ systems manifest poor health in individuals with common neuropsychiatric disorders? Findings This multicenter, population-based cohort study that included 85,748 adults with neuropsychiatric disorders and 87,420 healthy control individuals found that poor bodily health, particularly of the metabolic, hepatic, and immune systems , was a more marked manifestation of mental illness than brain changes. However, neuroimaging phenotypes allowed differentiation between different neuropsychiatric diagnoses. Meaning Treatment of severe neuropsychiatric disorders should recognize the importance of poor physical health and aim at restoration of brain and body function. |

Mental illness is associated with higher rates of chronic physical illnesses, including coronary heart disease, obesity, and diabetes compared to the general population. This contributes substantially to the global health and economic burden due to increased morbidity, disability and mortality. However, in psychiatric care and services, physical health has been neglected and inadequately managed for decades.

Despite increased awareness of physical health in psychiatry, recognizing and treating chronic physical illnesses remains a challenge. Patients’ poor physical health is likely to be underestimated due to existing disparities in health care for people with mental illness, such as lack of access to adequate primary care, overshadowing of diagnosis, and difficulties in recognizing and reporting problems. doctors of some patients. Therefore, more work is needed to understand the associations between mental and physical comorbidities, which may facilitate holistic and integrated care in psychiatry.

Most meta-research has focused on cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities in psychiatry. While infectious and immune-related comorbidities have also been investigated, the chronic disease burden of common diseases affecting other body systems is barely explored. The association between brain and body health, as well as associated disease risk and physical multimorbidity across body systems, therefore remains poorly characterized.

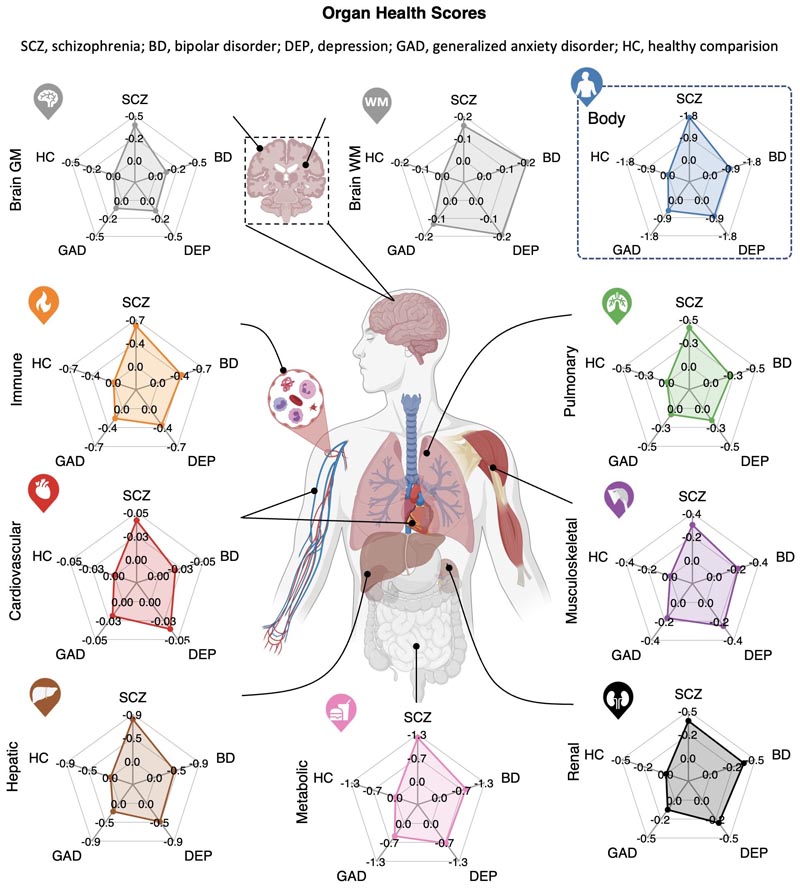

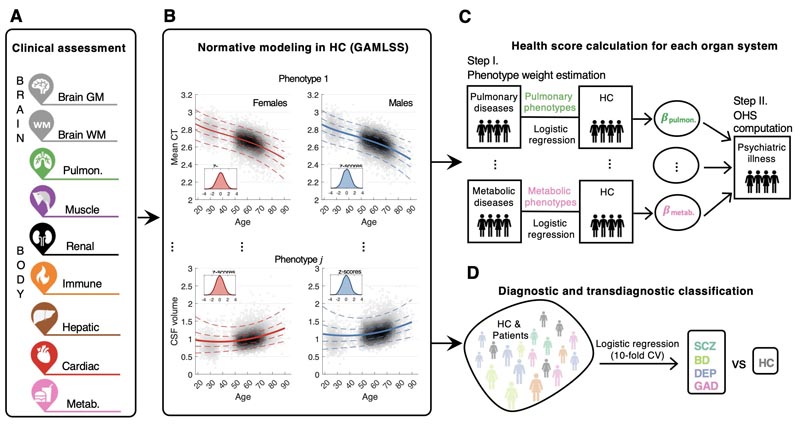

We systematically investigate brain and body health in common neuropsychiatric conditions (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder). Using brain imaging, physiological measures, and blood- and urine-based markers acquired in more than 100,000 people , we established composite organ health scores for brains and body systems. We calculated age- and sex-specific normative reference ranges for each organ health score based on healthy comparison individuals and quantified the extent to which individuals with the above conditions deviated from established normative ranges. This allowed us to develop multi-organ health profiles for each neuropsychiatric condition and estimate the relative effect of these profiles on the body systems and physical health of each individual.

Importance

Physical health and chronic medical comorbidities are underestimated, inadequately treated, and often overlooked in psychiatry. A multiorgan and systemic characterization of brain and body health in neuropsychiatric disorders may allow systematic evaluation of brain and body health status in patients and potentially identify new therapeutic targets.

Aim

Assess the health status of the brain and 7 body systems in common neuropsychiatric disorders.

Design, environment and participants

Brain imaging phenotypes, physiological measures, and blood- and urine-based markers have been harmonized across multiple population-based neuroimaging biobanks in the US, UK, and Australia, including Biobank from United Kingdom; Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank; Australian Aging Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Prospective Imaging Study of Aging; Human-Young Adult Connectome Project; and Human Connectome–Aging Project.

Cross-sectional data acquired between March 2006 and December 2020 were used to study organ health. Data were analyzed from October 18, 2021, to July 21, 2022. Adults ages 18 to 95 with a lifetime diagnosis of 1 or more common neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, generalized anxiety and a healthy comparison groupwere included.

Main results and measures

Deviations from normative reference ranges for composite health scores indexing the health and function of the brain and 7 body systems. Secondary outcomes included accuracy of classification of diagnoses (disease vs. control) and differentiation between diagnoses (disease vs. illness), measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

Results

85,748 participants with preselected neuropsychiatric disorders (36,324 men) and 87,420 healthy control individuals (40,560 men) were included in this study. Body health, especially scores indexing metabolic, liver, and immune health , deviated from normative reference ranges for all 4 neuropsychiatric disorders studied.

Poor body health was a more pronounced disease manifestation compared to brain changes in schizophrenia (AUC for body = 0.81 [95% CI, 0.79-0.82]; AUC for brain = 0 .79 [95% CI, 0.79-0.79]), bipolar disorder (body AUC = 0.67 [95% CI, 0.67-0.68]; brain AUC = 0 .58 [95% CI, 0.57-0.58]), depression (AUC for body = 0.67 [95% CI, 0.67-0.68]; AUC for brain = 0.58 [95% CI, 0.58-0.58]) and anxiety (AUC for body = 0.63 [95% CI, 0.63-0.63]; AUC for brain = 0.57 [95% CI, 0.57-0.58]).

However, 60] and mean AUC for brain = 0.65 [95% CI, 0.65-0.65]; depression-other: mean AUC for body = 0.61 [95% CI, 0.60-0.63] and mean AUC for brain = 0.65 [95% CI, 0.65-0.66 ]; anxiety-other: Mean AUC for body = 0.63 [95% CI, 0.62-0.63] and mean AUC for brain = 0.66 [95% CI, 0.65-0.66 ]. 60] and mean AUC for brain = 0.65 [95% CI, 0.65-0.65]; depression-other: mean AUC for body = 0.61 [95% CI, 0.60-0.63] and mean AUC for brain = 0.65 [95% CI, 0.65-0.66 ]; anxiety-other: Mean AUC for body = 0.63 [95% CI, 0.62-0.63] and mean AUC for brain = 0.66 [95% CI, 0.65-0.66 ].

Figure : Normative models and organ health scores for the brain and 7 body systems across the adult lifespan, using multimodal brain imaging, blood, urine, and physiological markers acquired in more than 100,000 people.

Conclusions and relevance

In this cross-sectional study, neuropsychiatric disorders shared a substantial and largely overlapping footprint of poor body health. Routine body health monitoring and comprehensive physical and mental health care can help reduce the adverse effect of physical comorbidity in people with mental illness.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, by establishing normative models of brain and body function across the adult lifespan using population-based cohorts, we map multisystem health profiles for 4 common neuropsychiatric disorders. We showed that individuals diagnosed with these neuropsychiatric disorders were not only characterized by deviations from normative reference ranges for brain phenotypes, but also had significantly poorer physical health across multiple body systems compared to their healthy peers. Poor physical health was a more pronounced manifestation of neuropsychiatric disease than brain health. However, brain phenotypes allowed for more precise differentiation between pairs of neuropsychiatric diagnoses.

Despite profound deviations from established normative reference ranges for multiple body systems (e.g., metabolic, hepatic, immune, and renal), chronic physical comorbidities often went undiagnosed , even years after evaluation of the condition. body function. Disparities in these physical health outcomes may reflect the lack of physical examination, preventive screening, intervention, and access to standard health care systems common among people with mental illness.

In all 4 neuropsychiatric disorder groups, the metabolic, liver, and immune systems consistently showed poor health scores. Poor metabolic health is consistent with the commonly reported increased risk of developing metabolic diseases, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity in people with mental illness and may be attributed in part to the adverse effects of antipsychotics and chronic diseases.

Chronic psychological stress is associated with mental illness and leads to dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the endocrine and metabolic systems.

Therefore, our findings of poor metabolic health in neuropsychiatric diseases could be due to chronic stress exacerbating a genetic disposition for these conditions through dysregulation of metabolic and endocrine pathways. Poor liver health may be associated with excessive alcohol consumption, higher rates of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection, and psychotropic drug-induced hepatotoxicity in people with mental illness. Conversely, poor immune health could be a driver or consequence of the reciprocally increased risk between immune-inflammatory response and psychiatric disorders. Although to a lesser extent, significantly worse kidney health was also observed in these patients, which may be related in part to the adverse effects of mood stabilizers, especially lithium, while poor lung and musculoskeletal health may be related. associated with smoking and behaviors related to sedentary lifestyle, physical inactivity, and social withdrawal.

Poor body health may also be associated with premature aging in middle age. Biological brain age deviates from chronological age in several brain disorders. This suggests an accelerated brain aging process and may explain why some people have an increased risk of age-related diseases. To test these hypotheses, longitudinal studies are needed to determine the interplay between brain and body health across the course of psychiatric illness.

While body phenotypes were generally more accurate than brain in diagnostic classification, classification models for brain phenotypes outperformed all body systems in differentiating distinct diagnoses. Our models are not intended for disease classification in clinical settings, but rather provide an alternative, quantitative mapping of how brain and body systems may be differentially affected in neuropsychiatric conditions. Our results suggest that the patterns of abnormal deviations in the brain were relatively different between different neuropsychiatric disorders. This distinction was stronger for schizophrenia compared to anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder, where the latter could not be accurately differentiated.

In complementary analyses, to provide a reference point, we compared our findings of poor body health to a common neurodegenerative condition (i.e., dementia). We found that dementia had the worst brain and body health of all the disorders studied. Although dementia is often associated with progressive gray matter loss, the most extreme deviations from normative ranges were observed in the metabolic and hepatic systems , consistent with all 4 neuropsychiatric conditions. It has been hypothesized that the combination of insulin resistance and liver dysfunction in dementia leads to inadequate clearance from the brain of amyloid and toxic metabolites produced by the liver, which cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to inflammation and pathology. cerebral.

Our results suggest that physical health may have deteriorated in these individuals, possibly contributing to the risk of developing dementia later in life. Prospective studies are needed to track organ health across the lifespan and identify when body and brain systems first deviate from the normative reference ranges established here. Future work is also needed to evaluate whether our organ health scores, especially metabolic and liver health scores, can predict the onset of dementia and allow early identification of individuals at risk for dementia.

Our findings provide biological evidence supporting the adoption of established preventive public health principles and strategies commonly used in the general population for physical illness (e.g., the Diabetes Prevention Program) in psychiatric care to complement psychotropic medication. specific to the disease and psychological treatments. This may be a cost-effective way to reduce disease burden and mortality in neuropsychiatric conditions.

The physical health of people with mental illness should be routinely assessed and appropriately managed to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve patient well-being. The organ-specific health scores developed in our study enabled a systematic and holistic assessment of brain and body health status in people with common neuropsychiatric disorders. More work is needed to determine whether our organ health scores can predict physical comorbidity before disease onset and identify individuals at risk for developing physical disease. This, in turn, could prompt new preventive strategies.

Final message In this study, marked deviations from normative reference ranges for brain and body health were evident in multiple organ systems in people with neuropsychiatric disorders in this study. The metabolic, liver, and immune systems showed the worst health and function for the disorders studied. Despite the unequivocal neural basis of common neuropsychiatric disorders, the findings of this study suggest that poor bodily health and functioning may be important manifestations of the disease that require ongoing treatment in patients. Routine body health monitoring and comprehensive physical and mental health care in psychiatric practice may provide cost-effective targets to reduce the adverse effect of physical comorbidity in people with mental illness. |