Over the centuries, many theories about chronic disease prevention have come and gone, but one recommendation has stood the test of time: A physically active lifestyle is a key behavior necessary for optimal health and disease prevention. . The importance of physical activity in cardiometabolic diseases such as the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has been recognized for centuries, and it has been two decades since the publication of clinical evidence from large randomized clinical trials based on results support the notion that increasing physical activity levels confers protection against the onset of type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Results from these lifestyle intervention studies support those derived from large observational cohorts suggesting an inverse relationship between self-reported physical activity levels and long-term T2D risk. As a result, most guidelines not only for the prevention of Type 2 diabetes, but also for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, recommend achieving a certain amount of physical activity, such as 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week through aerobic or resistance exercise or both.

While randomized clinical trials have been useful in establishing a causal role of physical activity in preventing cardiometabolic diseases, many scientific questions remain, including the “dose” of physical activity for optimal T2D risk reduction. Unfortunately, this issue has not yet been answered by large outcome-based randomized clinical trials. To provide clear and concise messages to our policymakers, health professionals, and the general public, more data is needed from large, rigorous studies with adequate assessment of minutes, intensity, and volume of physical activity. However, a large proportion of the observational studies published to date have been based on self-reported physical activity level. Studies using objective measures of physical activity-related energy expenditure (PAEE) have generally had limited sample sizes.

In the early 2000s, the UK government, through the Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health, began funding the UK Biobank, a prospective cohort including hundreds of thousands of participants. from the UK with deep phenotypes with anonymised data that has been made available to scientists around the world. Two decades after the launch of this study, the UK Biobank has become an inspiring example of data generation and sharing in health research. Among the plethora of phenotypes assessed in UK Biobank participants, questionnaire- and accelerometer-based assessments of physical activity habits were obtained in a subgroup of nearly 100,000 participants . Such a large study represented an unprecedented opportunity to further explore an important question.

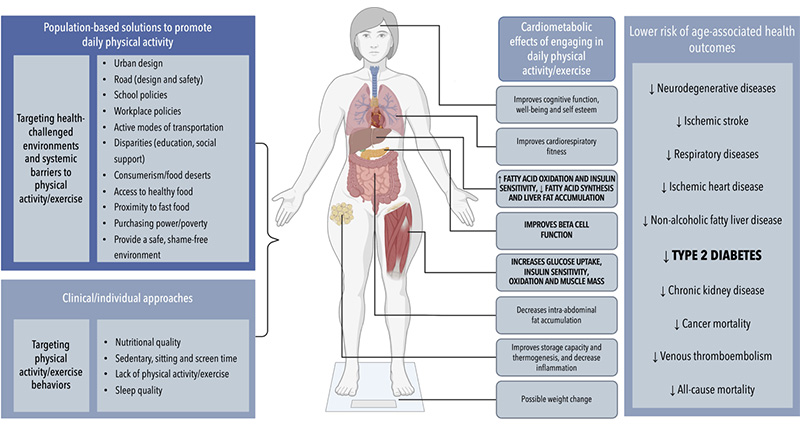

Figure: Implementing individual and population-based approaches to increase daily energy expenditure from physical activity may provide cardiometabolic benefits and decrease the long-term risk of age-associated health outcomes such as type 2 diabetes. In the study by Strain et al., a dose-response effect of volume and intensity of daily physical activity and risk of T2D was observed in 90,096 UK Biobank participants. These results suggest that people should be encouraged to increase daily PAEE for optimal cardiometabolic health and lower risk of T2D. Further analyzes from the UK Biobank revealed potential effects of higher daily PAEE on other age-associated health outcomes listed in the figure. It should be emphasized that people with a higher daily PAEE do not differ from people with a lower daily PAEE only by their personal will or awareness of the health benefits of physical activity. The presence of systemic barriers to physical activity may explain the large interindividual PAEE differences in the population. Systemic barriers that prevent people from engaging in daily physical activity and other lifestyle behaviors associated with cardiometabolic health are also presented. These barriers will also need to be addressed to increase physical activity habits and reduce the social burden associated with T2D.

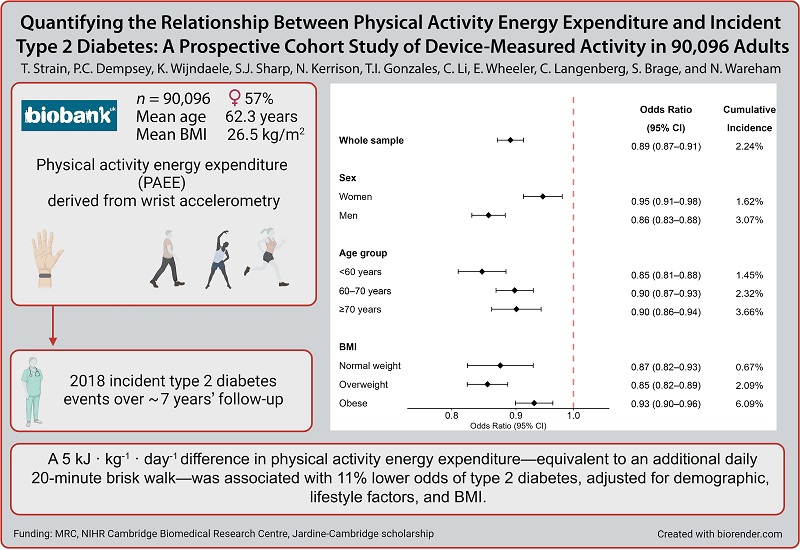

Published in Diabetes Care , building on their previous work on the impact of physical activity and health risk measured with wearable devices Strain et al. present the results of a prospective UK Biobank investigation into PAEE and incident T2D.

Goals To investigate the association between accelerometer-derived physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) and incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in a cohort of middle-aged adults and within subgroups. Design and methodology Data were from 90,096 UK Biobank participants without prevalent diabetes (mean age 62 years; 57% female) who wore a wrist accelerometer for 7 days. PAEE was derived from wrist acceleration using a population-specific method validated against doubly labeled water. Logistic regressions were used to evaluate associations between physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), its underlying intensity, and incident T2D, determined using hospital episode data and mortality through November 2020. Models were progressively adjusted for demographic factors. , lifestyle and BMI. Results The association between physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) and T2D was approximately linear (n = 2018 events). We observed 19% (95% CI: 17–21) lower odds of T2DM per 5 kJ · kg −1 · day −1 in PAEE without adjustment for BMI and 11% (9–13) with adjustment for BMI. The association was stronger in men than in women and weaker in those with obesity and greater genetic susceptibility to obesity. There was no evidence of effect modification by genetic susceptibility to T2D or insulin resistance. For a given level of physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), the odds of T2D were lowest among those engaging in more moderate to vigorous activity. Conclusions There was a strong linear relationship between physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) and incident T2D. A difference in PAEE equivalent to an additional 20-minute daily brisk walk was associated with a 19% lower odds of T2D. The association was very similar in all population subgroups, supporting physical activity for diabetes prevention in the entire population.

Reference : Quantifying the Relationship Between Physical Activity Energy Expenditure and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study of Device-Measured Activity in 90,096 Adults. Tessa Strain, Paddy C. Dempsey; Katrien Wijndaele; Stephen J. Sharp; Nicola Kerrison; et al. Diabetes Care 2023; 46(6):1145–1155 https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-1467 PubMed: 36693275 |

The researchers first calculated PAEE based on data from a wearable device worn on the wrist for 7 days (a method validated by measuring gold standard stable isotopes) in 90,096 UK Biobank participants without T2D. During follow-up, 2,018 people received a diagnosis of T2D. A remarkably linear inverse relationship was found between PAEE and the risk of T2D. The authors then proposed that a PAEE equivalent to a 20-minute brisk walk could reduce the risk of developing T2D by almost 20%. Additional low-intensity physical activity was associated with even lower odds of T2D, while higher-intensity activity appeared to provide additional benefits with a given amount of PAEE.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that when it comes to physical activity for T2D prevention, something is better than nothing, more is better, and sooner is better.

The benefits of physical activity are seen throughout adult life. Therefore, achieving a higher volume of daily physical activity and higher intensity at any volume may be important to minimize the risk of T2D. Importantly, a greater volume of physical activity can also be achieved by adhering to a physically active lifestyle early in life. For those who were sedentary in their young adult lives, the study suggests that it is never too late to become physically active to reduce the risk of T2D.

Interestingly, this dose-response effect is not observed with all cardiometabolic diseases, for example with CVD. Using a similar approach, the authors reported a significant impact of achieving minimal PAEE volume but a more modest effect of increasing the dose of physical activity on CVD prevention. However, the intensity of physical activity was more linearly associated with CVD risk, suggesting that strategies based on increasing the volume and intensity of physical activity according to individual preferences can prevent the occurrence of a wide range of cardiometabolic diseases.

This study may also provide new and important information on the pathobiology of T2D . For example, the authors reported large absolute differences across BMI categories and that BMI slightly mediated the relationship between higher PAEE and lower risk of T2D. Although the relationship between physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) and body weight was overall modest, a high daily PAEE can have important effects on daily energy turnover and partitioning, as well as distribution of energy. body fat .

High physical activity energy expenditure ( PAEE) results in glycogen depletion , which increases glucose storage space and improves insulin sensitivity . Increasing glucose uptake and oxidation in lean tissues such as skeletal muscle and liver relieves pressure on adipose tissue for storage of unused energy, improves adipose tissue storage capacity and thermogenesis, and reduces inflammation , all of which are factors that contribute to reducing the risk of T2D.

Mobilization of “ectopic” lipids from skeletal muscles, liver, pancreas, and/or abdomen could also contribute to the alleviation of peripheral insulin resistance and improve β-cell function. These metabolic improvements associated with more physical activity may not necessarily require substantial body weight loss in some people, which explains why physical activity and exercise can prevent the onset of T2D even in the absence of changes in BMI .

These findings should encourage clinicians to 1) inspire their patients that they are capable of daily physical activity, regardless of their weight status, 2) recognize the limitations of BMI for the assessment of metabolic status or general health, 3) evaluate physical activity level as well as diet or sleep quality as “lifestyle vital signs” , and 4) promote healthy lifestyles in all people, regardless of the impact of such interventions on body weight.

An active lifestyle should first be promoted for health and not as a weight loss strategy.

The authors themselves acknowledge the limitations of this important study. Of course, causality cannot be inferred from an observational study design. Furthermore, physically active people do not differ from more sedentary people simply by their personal will or awareness of the health benefits of physical activity. Dozens of socioeconomic and environmental-related factors also influence population physical activity levels and health risks. From urban design, traffic safety and public transportation policies to the way our families, schools, workplaces and communities are organized and financed, many factors outside of our individual control shape our daily travel habits. physical activity, whether we live in urban, suburban, or rural areas.

Many children and adolescents do not have equal opportunities to live playing organized sports or access recreational physical activities. There are large socioeconomic disparities regarding access to resources and environments that enable an active lifestyle. Therefore, social factors influence both physical activity habits and disease trajectories, and will need to be addressed if we are to be successful in promoting a sustainable physically active lifestyle. Addressing environmental and systemic barriers to physical activity should be among our top priorities if we want to slow the progression of T2D.