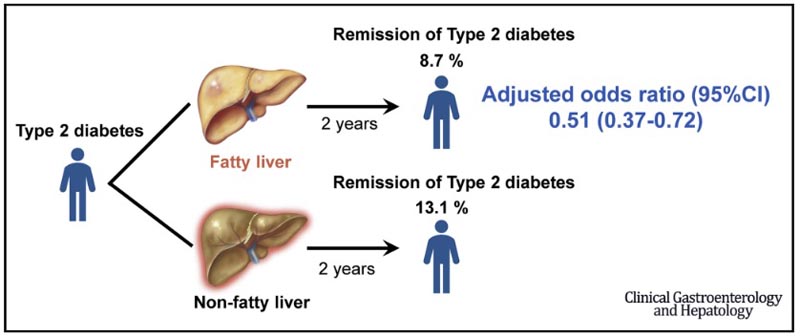

Inverse association between fatty liver at baseline and type 2 diabetes remission over a 2-year follow-up period

What you need to know Background There is no longitudinal evidence on whether fatty liver reduces the chances of type 2 diabetes remission. Results Remission of type 2 diabetes over a 2-year period was less common in people with fatty liver detected at baseline ultrasound. Improvement in fatty liver was independently associated with type 2 diabetes remission. Implications for patient care Improvement in fatty liver was independently associated with type 2 diabetes remission. Strategies to improve fatty liver may increase the chances of type 2 diabetes remission. |

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is increasing worldwide. In 2015, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that there were 415 million adults with type 2 diabetes and 5 million deaths caused by this disease worldwide.

T2DM is often considered progressive and irreversible, but T2DM remission is possible. In fact, type 2 diabetes remission was ranked as the top priority for type 2 diabetes research by patients and healthcare professionals in the UK. Remission of type 2 diabetes generally refers to the maintenance of nondiabetic levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) without active antidiabetic treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes.

During the last decade, remission of T2DM has been studied in patients with T2DM undergoing metabolic surgery. Recently, health behavior interventions, including, for example, low-calorie diets, have been used to achieve remission of type 2 diabetes and the effectiveness of such interventions could be related to a reduced amount of fat in the liver.

Fatty liver ( FL) is the most common liver abnormality. In more than half of T2D patients, FL can be detected even by ultrasound, which is relatively insensitive to mild hepatic steatosis.

FL may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes by increasing hepatic insulin resistance and hepatic glucose production.

FL may also interfere with remission of type 2 diabetes, and reducing the amount of fat in the liver may promote remission of type 2 diabetes. In fact, some small studies (n < 100) have shown that Health behavior interventions can result in remission of type 2 diabetes and a reduction in the amount of fat in the liver on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

However, in those studies, T2DM patients with LF were not compared with other T2DM patients who did not have LF, so it is still unclear whether LF negatively affects T2D remission. Furthermore, inferring a causal relationship between FL and a subsequent reduced incidence of T2D remission requires knowledge of their temporal relationship. To the best of our knowledge, there is no direct evidence that LF at baseline presents odd future remission of type 2 diabetes.

Although MRI is better at detecting and classifying FL in individual patients, ultrasound is nevertheless useful for comparisons between populations and between research groups.

- In this ultrasound-based cohort study, we investigated the association between fatty liver (FL) at baseline and subsequent remission of type 2 diabetes.

- We also evaluated the impact of reducing the amount of fat in the liver on the remission of type 2 diabetes.

Background and objectives

Improving fatty liver may be necessary for type 2 diabetes remission. However, there is no longitudinal evidence on whether fatty liver reduces the chances of type 2 diabetes remission.

We investigated the association between fatty liver and type 2 diabetes remission (the primary analysis), and also the association between fatty liver improvement and type 2 diabetes remission (the secondary analysis).

Methods

We collected data from 66,961 people who were screened for type 2 diabetes from 2008 to 2016 at a single center in Japan.

The primary analysis included 2,567 patients with type 2 diabetes without chronic kidney disease or a history of hemodialysis who underwent ultrasound screening for fatty liver, all of whom had follow-up tests, including blood tests, for a median of 24.5 months after the initial ultrasound. .

The secondary analysis included 1,833 participants with fatty liver at baseline who underwent a second ultrasound, and participants who had fatty liver at baseline but not at the second visit were considered to have had fatty liver improvement.

Remission of type 2 diabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level below 126 mg/dl and an HbA1c level below 6.5% for more than 6 months without antidiabetic drugs. Odds ratios (ORs) of type 2 diabetes remission were calculated using logistic regression models.

Results

A smaller proportion of patients who had fatty liver detected by ultrasound at baseline (8.7%, 167/1910) had remission of type 2 diabetes during the follow-up period than patients without fatty liver (13.1%, 86/657).

Fatty liver at baseline was associated with a lower likelihood of type 2 diabetes remission (multivariable-adjusted OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.37–0.72).

A greater proportion of patients who had improvement in fatty liver had remission of type 2 diabetes (21.1%, 32/152) than patients without improvement in fatty liver (7.7%, 129/1681).

Improvement in fatty liver was associated with a higher likelihood of type 2 diabetes remission (multivariable-adjusted OR, 3.08; 95% CI, 1.94–4.88).

Discussion

In this ultrasound-based cohort study, FL was inversely associated with T2DM remission.

Patients with less liver fat were more likely to achieve T2DM remission than those with more liver fat.

An inverse association between FL and T2DM remission was found even when the analysis was restricted to data from participants not taking antidiabetic drugs, and even when the analysis was restricted to data from participants who were not overweight or obese (BMI <25kg/m2). To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to show such an inverse association. Furthermore, we found that FL improvement was also associated with type 2 diabetes remission.

Taken together, these results imply that reducing liver fat may promote remission of type 2 diabetes.

The results of this longitudinal study are consistent with health behavior intervention studies showing simultaneous improvement in FL and T2DM remission. Lim et al conducted a low-calorie diet intervention in 11 people with T2DM and compared them to age-, sex-, and weight-matched control subjects without diabetes. At the end of 1 week of the low-calorie diet, both FPG and liver fat of people with T2DM had decreased, and were similar to those of control subjects without diabetes.

Additionally, Taylor et al performed a subanalysis of their cluster-randomized study showing that a low-calorie diet could promote remission of type 2 diabetes. In the subanalysis, liver fat in patients with weight loss and remission of T2DM decreased to a normal level, and suggested that improvement of LF was required for remission of T2DM.

These studies did not compare T2DM patients who had FL with those who did not have FL, with respect to T2DM remission. Additionally, previous studies included only patients with diabetes who were overweight or obese, but in the present study almost half of the participants were not overweight or obese .

The present results suggest that improvement of FL may be an important factor in the remission of type 2 diabetes.

A possible mechanism underlying an inverse association between FL at baseline and subsequent T2D remission involves hepatic insulin resistance through excess diacylglycerol. Diacylglycerol is a hydrophobic lipid in cell membranes and lipid droplets, and people with FL also have excess diacylglycerol in the liver. Excess diacylglycerol could inhibit hepatic insulin receptors and cause hepatic insulin resistance, leading to uncontrolled hepatic glucose production.

Unfortunately, we do not have the data that would be necessary to investigate the previously hypothesized mechanism, and longitudinal studies that include information on hepatic insulin and diacylglycerol resistance are clearly needed. Furthermore, additional studies focusing on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, including in ethnic groups other than those studied here, are warranted to better understand the relationship between liver fat and type 2 diabetes remission.

There are several limitations to this study.

First, we do not have information on the duration of type 2 diabetes or the types of antidiabetic drugs used. In fact, there were fewer participants taking antidiabetic medications in the LF group than in the non-LF group at baseline, and different antidiabetic medications are known to affect LF differently. Therefore, we restricted the analysis to data from participants who were not taking antidiabetic drugs at baseline. That didn’t change the results: FL was inversely associated with subsequent type 2 diabetes remission in participants who were not taking antidiabetic medications at the start of the study.

Second, FL was not confirmed by examination of biopsy specimens or by MRI, but was detected by ultrasound. The presence of hepatic fat is underestimated on ultrasound when there is <20% fat and the results of this study may not be generalizable to patients with mild FL. However, ultrasound is recommended as a first-line imaging technique to detect FL in patients with T2DM.

Therefore, the use of ultrasound in the present study to detect FL is applicable to clinical practice, although it must be taken into account that the precision of ultrasound is lower than that of MRI and that false negative results are more likely. in patients with mild FL. Furthermore, we do not have semiquantitative ultrasound data that would allow us to assess the degree of improvement in FL or FL. Further studies are needed to evaluate the dose-response relationship of FL or FL improvement with remission of T2D.

Third, interobserver agreement regarding the finding of FL on ultrasound was not assessed. Instead of interobserver agreement, we assessed agreement between US-based FL and CT-based FL among people who underwent both US and CT, and found moderate agreement.

Fourth, data on only 72% of participants were available for follow-up, probably because medical examinations were voluntary. To assess selection bias , we compared the baseline characteristics of participants for whom follow-up data were available with those of participants for whom follow-up data were not available, and found no substantial differences in almost all characteristics. initials. However, the proportion of false-negative results regarding FL at baseline could have differed between participants with and without follow-up.

Fifth, we do not have data on factors responsible for type 2 diabetes remission (e.g., lifestyle interventions and medications, such as vitamin E), and these should be investigated in future studies.

Finally, generalizability may be limited by the fact that the majority of participants were Japanese. Studies in other populations and studies using MRI to obtain a more accurate measurement of liver fat are warranted.

Conclusions This is the first longitudinal study to show an inverse association between FL detected by ultrasound and subsequent remission of T2DM. This inverse association was found even among participants who were not taking antidiabetic medications and among those who were not overweight or obese at the start of the study. We also found that FL improvement detected by ultrasound was associated with T2DM remission. These results support 2 conclusions:

If those findings are verified in future clinical trials, information from noninvasive assessment of liver fat could be used to promote type 2 diabetes remission and identify patients who are unlikely to achieve remission. Over a follow-up period of approximately 2 years , type 2 diabetes remission was less common in people with ultrasound-detected fatty liver, and fatty liver improvement was independently associated with type 2 diabetes remission. |