Description

This expert review summarizes approaches to pain management in gut-brain interaction disorders. It focuses specifically on approaches to pain that persist if first-line therapies aimed at addressing the visceral causes of pain are unsuccessful. The roles of a patient-provider therapeutic relationship, pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, and opioid avoidance are discussed.

Methods

This was not a formal systematic review, but rather relied on a review of the literature to provide statements of best practice recommendations. No formal grading of the quality of the evidence or the strength of the recommendation was made.

Abbreviations used in this document:

5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine), CAPS (centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome), DGBI (disorders of gut-brain interaction), FD (functional dyspepsia), IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), PPI (pump inhibitor of protons), RCT (randomized controlled trial), SNRI (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), TCA (tricyclic antidepressant)

Disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional dyspepsia (FD), and centrally mediated abdominal pain syndrome (CAPS), are present in more than 40% of the population world.

Most patients with DGBI are initially treated with therapies that target visceral stimuli, such as food and bowel movements. For example, patients with esophageal or gastroduodenal DGBI, such as functional heartburn or FD, are often treated with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which can be effective.

First-line dietary treatments, antidiarrheals, and laxatives are frequently used in IBS, but have limited evidence of effectiveness for abdominal pain.

Unfortunately, a subset of patients with DGBI continue to experience pain, which negatively impacts health-related quality of life and leads to healthcare utilization.

The management of patients with pain unresponsive to first-line therapies targeting visceral stimuli is complex and influenced by a variety of cognitive, affective, and behavioral factors, including learning and expectations around pain, and other psychosocial modifiers such as overlapping mood and anxiety disorders.

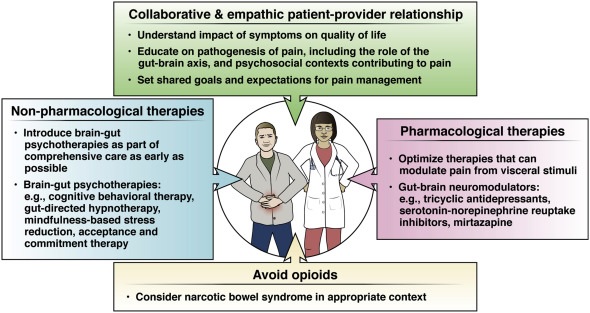

Effective pain management requires establishing a collaborative relationship between patient and provider and avoiding medications with potential for misuse, such as opioids (Figure 1).

Management options include pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. This Clinical Practice Update focuses on the management of patients with DGBI whose pain has not improved with therapies directed at visceral stimuli. This review does not look at the use of complementary or alternative therapies such as marijuana and does not apply to the treatment of pelvic or abdominal wall pain syndromes.

Best Practice Tip 1

Effective management of persistent pain in gut-brain interaction disorders requires a collaborative, empathetic, and culturally sensitive relationship between patient and provider. The development of a collaborative and empathetic relationship between the patient and healthcare provider is required to address the management of persistent pain in DGBI.

Patients may have seen multiple providers without clear benefit or improvement and may be dissatisfied with their health care. A sensitive and nonjudgmental approach to the patient will integrate medical care with psychosocial information to achieve desired outcomes. Due to cultural differences in the understanding and interpretation of pain, as well as preferred management strategies, it is also necessary to approach pain in a culturally sensitive manner for it to be effectively reported by patients and treatment.

Initially, the medical history should be obtained through a non-directed interview with open questions. Closed questions can be used later to clarify. Additionally, addressing the impact of symptoms on patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning explicitly, through the use of open-ended questions, helps establish rapport and allows the provider to target interventions more specific to improve function. Examples include : "how do your symptoms interfere with your ability to do what you want in your daily life?" or "How do these symptoms most affect your life?" These questions can also help providers identify patients who might benefit most from behavioral health interventions.

Asking about symptom-specific anxiety can also help gastroenterology providers understand and address patients’ concerns. For example, understanding that symptoms do not necessarily indicate the presence of undiagnosed cancer, or indicate that surgery is required, can alleviate significant anxiety and allow treatment aimed at improving quality of life. Gastroenterology providers must demonstrate a willingness to address the medical and psychosocial aspects of the patient’s illness. Many patients are relieved to know that a diagnosis of IBS or FD does not shorten life expectancy.

Providers can understand the patient’s perspective on their symptoms by asking questions such as: “what do you think is causing your symptoms,” “why are you coming to see me now,” and “what are you most concerned about with your symptoms?” "The patient and provider should come to a set of shared expectations and goals around pain relief and management and continue to review and modify them as necessary as the therapeutic relationship develops. In general, understand the patient’s experience with your pain and its impact on your functioning allows providers to develop care plans to more directly address concerns and improve quality of life.

Best Practice Tip 2

Healthcare providers must master patient-friendly language about the pathogenesis of pain, taking advantage of advances in neuroscience and behavioral sciences. Providers must also understand the psychological contexts in which pain is perpetuated.

It is critical that patients hear the following from their gastroenterology provider:

- Chronic pain from DGBI is real.

- Pain is perceived from sensory signals that are processed and modulated in the brain.

- Peripheral factors can cause increased pain.

- Pain is modifiable.

Unlike acute pain, which may be viewed as informative or alarming (e.g., a perforated appendix), chronic gastrointestinal pain is perpetuated by a complex interaction of nerve impulses, which may be unrelated (e.g., CAPS) or be disproportionate to actual sensory information (e.g., postprandial fullness).

These impulses, originating in the enteric nervous system or digestive viscera, activate a wide range of perceptual and behavioral brain networks that amplify the painful experience. Beyond the sensory-discriminative component of pain (location, intensity), higher-order brain processes can be cognitive-evaluative (based on previous experiences/expectations) and affective-motivational (displeasure/fear/desire to act).

We can tell patients that these sensory inputs may result from increased attention to innocuous (or normal) abdominal sensations as the brain continues to search for potential threats from the gut, based on previous experience with infections, injuries, or inflammation (e.g. E.g., post-infection IBS or FD) and instead of shutting down (down-regulating) and trusting in its own safety, the brain mistakenly activates higher-order (and unhelpful) processes. This framework, drawn from the fear-avoidance model of pain, helps providers explain why some people have more pain than others, despite a similar diagnosis, and instills hope that a change in the approach to pain could improve the function.

The context in which patients experience pain is also important. It is helpful to explain that the factors that initiate problems (e.g., infection, surgery, stressful life event) are not always the same as those that perpetuate the problem. Psychological inflexibility , or focusing too much on one cause or solution, is common in chronic pain syndromes and interferes with acceptance of pain and response to treatment.

Solicitation of pain by members of the patient’s support system (routinely asking about pain) or the presence of psychological comorbidity such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, or somatization also interferes with pain processing.

People with chronic pain also tend to display pain hypervigilance behaviors , such as checking for pain after eating or having a bowel movement. They may avoid activities that are important to them for fear of developing symptoms, increasing the impact of chronic pain on daily function.

Finally, pain catastrophizing , the process of overestimating the severity of pain along with feelings of helplessness, is associated with increased healthcare utilization and opioid misuse. Providers should avoid engaging in pain catastrophizing by avoiding language that the patient “shouldn’t be in so much pain” or continuing to order testing to find the “cause” of the pain.

Best Practice Tip 3

Opioids should not be prescribed for chronic gastrointestinal pain due to a disorder of the gut-brain interaction. If patients are referred to opioids, these medications should be prescribed responsibly, through multidisciplinary collaboration, until they can be discontinued.

The use of opioid medications for the treatment of non-cancer pain is under great scrutiny due to the risks of opioid use disorders and overdose-related deaths. Gastroenterology providers are frequently asked to see patients who have been treated with long-term opioids for associated gastrointestinal symptoms. In patients with chronic gastrointestinal conditions, including DGBI, the use of opioid medications is not uncommon, but is ineffective and potentially harmful.

Patients with overlapping inflammatory bowel disease and DGBI are more likely to use opioids than those without DGBI, as are patients with DGBI compared to those with structural diagnoses.

Patients using long-term opioids are at risk of developing narcotic bowel syndrome, which is often unrecognized and occurs in approximately 6% of this population. Narcotic bowel syndrome is characterized by chronic or recurrent paradoxical increases in abdominal pain, despite continued or increasing doses of opioids. It is associated with a significant deterioration in quality of life. However, narcotic bowel syndrome can be difficult to diagnose because its symptoms overlap with IBS and CAPS. In fact, it may coexist and complicate the management of patients with painful DGBI.

A high index of suspicion is necessary for a diagnosis of narcotic bowel syndrome because continued treatment with opioids can lead to clinical worsening and repeated medical evaluations. Using techniques to develop an open, collaborative relationship between patient and provider and patient-friendly language to explain the pathogenesis of NBS can help with patient acceptance of this disorder and collaboration in its management.

It is also important to recognize that tramadol is considered an opioid and has the potential for addiction and other opioid-associated adverse events. The primary treatment is cessation of opioids, if possible, but behavioral and psychiatric approaches are needed for long-term management and reduction of relapse.

Patients who have already received opioid medications may be referred to a gastroenterologist. In this situation, providers must prescribe opioids responsibly in a multidisciplinary setting, with monitoring for effectiveness, side effects, and potential for abuse until other forms of pain management can be implemented.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guide to prescribing opioids for chronic pain is a helpful resource in this regard.

Best Practice Tips 4

Non-pharmacological therapies should be routinely considered as part of comprehensive pain management and, ideally, should be addressed from the outset of care.

Gut-brain psychotherapies are brief, evidence-based interventions that have been tailored to address the unique pathophysiology associated with gut-brain dysregulation. Gut-brain psychotherapies can be highly personalized, based on an individual patient’s needs, symptoms, and context, and can therefore be used across the spectrum of painful DGBI, including IBS, FD, and CAPS. It is important for the gastroenterology provider to include from the beginning of care the role of gut-brain psychotherapies in the treatment of chronic gastrointestinal pain.

Although many patients will not require this level of care, patients are more likely to adopt these recommendations when they do not feel that it is a last-ditch effort, after all other interventions have failed, or as a " punishment" for not improving with treatments. traditional treatments. Additionally, these therapies are typically well tolerated with minimal side effects. There are some classes of gut-brain psychotherapy that have been shown to improve painful symptoms specifically, and it is helpful for the gastroenterology provider to become familiar with the focus, structure, and goals of each intervention to increase clinical use.

It is also important for the gastroenterology provider to identify some mental health providers in their community with whom they can collaborate if such services are not already integrated.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is a brief (4 to 12 sessions) gut-brain psychotherapy that focuses on the remediation of skill deficits such as pain catastrophizing, pain hypervigilance, and visceral anxiety through techniques such as cognitive reframing, exposure, relaxation training and the flexible problem. solve.

There are over 30 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) supporting the use of cognitive behavioral therapy for IBS in multiple forms of delivery (self-administered, web-based, group, or individual).

Gut-directed hypnotherapy is another well-tested gut-brain psychotherapy that focuses on somatic awareness and down-regulation of pain sensations through guided imagery and post-hypnotic suggestions. It can also be delivered in groups or online, and by non-mental health professionals. There is evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses for pain relief in IBS and evidence from RCTs in CAPS and FD.

Mindfulness- based stress reduction has also been shown to be effective in irritable bowel syndrome and musculoskeletal pain syndromes. In IBS, mindfulness has been shown to improve specific symptoms such as constipation, diarrhea, bloating, and specific gastrointestinal anxiety, especially in women. In addition, it can reduce visceral hypersensitivity, improve the cognitive assessment of symptoms and improve quality of life. This approach can also be applied by non-mental health professionals.

Acceptance and commitment therapy is a promising approach to chronic gastrointestinal pain that combines acceptance and mindfulness strategies with behavior change techniques to reduce suffering. It is believed to work by improving psychological flexibility through the use of metaphors, paradoxes, and experiential exercises designed to help the patient build a meaningful life despite chronic pain. In the pain literature more broadly, acceptance and commitment therapy is a highly effective therapy.

Again, it is important for the gastroenterology provider to become familiar with the gut-brain psychotherapies that are available, but defer decisions about treatment choice to the mental health provider.

Best Practice Tips 6

Healthcare providers should become familiar with some effective neuromodulators , know the dosage, side effects, and goals of each, and be able to explain to the patient why these medications are used for the treatment of persistent pain. The enteric nervous system shares its embryological development with the brain and spinal cord and, therefore, its neurotransmitters and receptors. This gut-brain axis , with its norepinephrine, serotonergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmitters, is important for gut motor function and visceral sensation. Therefore, drugs that act on these pathways also have effects on gastrointestinal symptoms.

Low-dose antidepressants , now called gut-brain neuromodulators , are used in painful DGBI because they have pain-modifying properties in addition to their known effects on mood. Such medications include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and others, such as mirtazapine.

Of these, SSRIs, which act solely on 5-HT receptors, have the least analgesic effect, and the 2014 AGA guideline suggested not using them for patients with IBS, while the 2021 American College of Gastroenterology guideline did not make a solid recommendation for treatment. In contrast, drugs such as TCAs, SNRIs, and mirtazapine, which have norepinephrine effects, have greater effects on pain. These medications should be started at a low dose and titrated according to symptom response and tolerability, and patients should be aware of potential side effects.

As discussed above, opioid drugs should be avoided in cases of painful DGBI, but low-dose naltrexone can have analgesic effects without gastrointestinal side effects. The efficacy of TCAs and SSRIs has been studied in several painful DGBIs including functional heartburn, FD, and IBS. A trial of imipramine in functional heartburn showed no benefit from active treatment, while an RCT of citalopram showed superiority over placebo for hypersensitive esophagus. There is more data for TCA and SSRIs in both FD and IBS.

SNRIs have been less studied, although there has been a trial of venlafaxine in FD that showed no benefit. The evidence in IBS is limited to case series of patients taking duloxetine. Interestingly, there is high-quality evidence that duloxetine is effective in other chronic pain disorders, such as fibromyalgia and low back pain.

Mirtazapine was used in a small trial in FD, but appeared to have greater effects on early satiety than epigastric pain. A recent trial in IBS patients with diarrhea showed significant improvements in abdominal pain with mirtazapine. An open-label trial of low-dose naltrexone in IBS showed a significant improvement in pain-free days.

Conclusions Management of persistent pain in DBGI is challenging and complex. Patients typically present with coexisting psychiatric comorbidities and a limited range of coping skills. This clinical practice update presents recommendations on best practices to assist in the management of these patients through improved patient-provider communication and a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Developing a collaborative and empathetic relationship between patient and provider can improve patient anxiety, functional status, and quality of life, while helping patients understand the pathogenesis of their condition and allowing for the introduction of appropriate pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. Avoiding opioid medications is critical to preventing the development of opioid use disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome. In patients who do not respond to the measures described here, the involvement of a pain management specialist may be required. Overall, management of DGBI patients with persistent pain requires a multipronged approach to optimize patient outcomes. |