Summary Acute pericarditis accounts for around 5% of presentations with acute chest pain. Tuberculosis is a major cause in the developing world, however, in the UK and other developed settings, the majority of cases are of idiopathic/viral origin. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) remain the cornerstone of treatment. At least one in four patients is at risk of recurrence. Adding 3 months of colchicine can more than halve the risk of this (number needed to treat = four). Low-dose steroids may be useful as second-line agents to treat recurrences as adjuncts to NSAIDs and colchicine, but should not be used as first-line agents. For patients who fail this approach and/or are corticosteroid dependent, the interleukin-1β antagonist anakinra is a promising option, and for the few patients who are refractory to medical treatment, surgical pericardiectomy may be considered. The long-term prognosis is good with <0.5% risk of constriction for patients with idiopathic acute pericarditis. |

Key points

|

The pericardial sac is formed by an internal mesothelial layer that covers the heart (visceral) and covers an external fibrous layer on which the mesothelium is reflected (parietal layer). It produces up to 50 ml of fluid that serves to lubricate the movement of the heart and generally serves to prevent excessive cardiac movement and anchor it in the mediastinum.

Pericardial disease results from inflammation of the pericardium, which in turn can lead to an effusion; and rigidity of the pericardium leading to constriction syndrome. The visceral pericardium is innervated by branches of the sympathetic trunk that carry pain afferent fibers in a cardiac distribution and the vagus that can trigger vagally mediated reflexes in acute pericarditis. In contrast, the parietal and fibrous pericardium is innervated by somatosensory branches of the phrenic nerve that can give rise to referred pain to the shoulder.

Diagnosis and initial investigation

Pericarditis is a relatively common cause of chest pain accounting for approximately 5% of all admissions for chest pain.

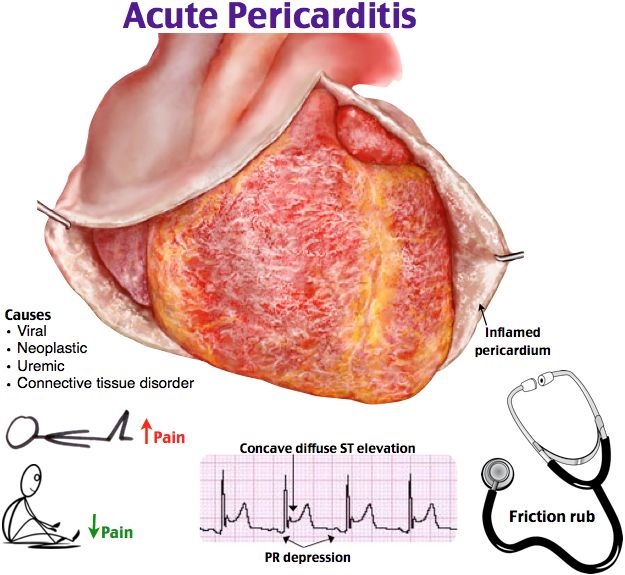

In the UK, most cases are idiopathic and probably of viral origin, in contrast to the situation in the developing world where tuberculosis is a disease. common cause. Patients typically complain of chest pain that is central, worse with inspiration or lying down, and better with sitting forward.

- Auscultation may reveal a characteristic pericardial friction rub , although this may be evanescent and may require repeat evaluation for detection.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) classically reveals generalized saddle-shaped ST elevation with associated PR depression and is useful in excluding other causes of chest pain .

- The chest x-ray is usually normal unless there is a significant pericardial effusion.

- Inflammatory markers ( erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) are often elevated and there may also be slight elevations in troponin if there is associated myopericarditis.

More significant elevations and/or clinical or sonographic features of left ventricular dysfunction should prompt consideration of myocarditis instead or so-called perimyocarditis where myocardial involvement predominates.

The diagnosis of pericarditis requires the presence of two of the typical symptoms or signs:

- pericardial chest pain

- pericardial rub

- ST elevation and/or generalized PR depression

- New or increasing nontrivial pericardial effusion.

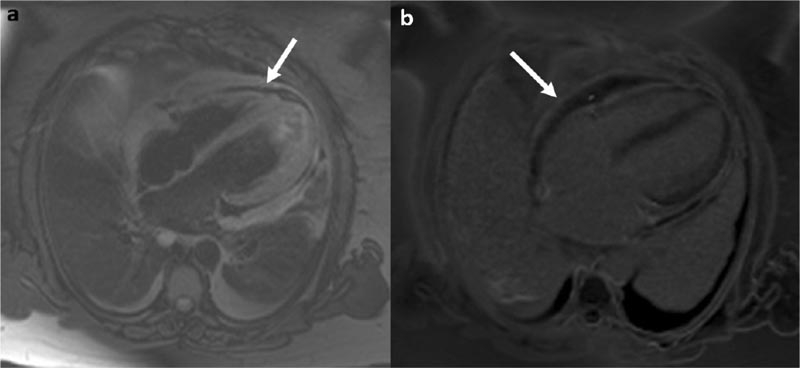

If diagnostic uncertainty persists, cardiovascular MRI with T2-weighted images and late gadolinium enhancement may be useful to confirm the presence of any pericardial inflammation and exclude concomitant myocarditis and other differences (Figure 1).

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute pericarditis. a) T2-weighted spin echo image showing the pericardium with acute inflammation that appears high signal (arrow). There are also associated bilateral pleural effusions. b) Late gadolinium enhancement sequence revealing avid contrast uptake by the inflamed pericardium (arrow). Healthy pericardium does not improve with contrast.

Evolution

Most cases resolve within a month and the yield of investigation for a precipitant, particularly viral serology, is low and generally not recommended .

- A pericarditis that persists for more than 4 to 6 weeks but less than 3 months is called incessant .

- Pericarditis that persists more than 3 months is called chronic .

- If there is a period of intermediate remission lasting more than 4 to 6 weeks, the term recurrent is used .

These terms are relevant to therapeutic decision making and research avenues.

Risk Stratification

A complete history is a vital step in risk stratification. Several clinical features may portend an increased risk of complications and indicate the need for initial inpatient investigations and an active search for an etiology:

- fever > 38°C

- gradual onset of symptoms

- presence of a large spill (> 20 mm)

- tamponade physiology features

- lack of response to treatment after 1 week of anti-inflammatories.

The presence of myopericarditis , history of trauma, use of oral anticoagulants, and history of immunosuppression are considered minor adverse prognostic markers that may also trigger hospital evaluation.

Treatment

For all patients, current guidelines recommend exercise restriction for the duration of symptoms and for at least 3 months in athletes, although this is based on expert consensus opinion rather than solid evidence.

Acute pericarditis can be treated with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen at 600 mg three times a day (tds) for 1 to 2 weeks, usually with a proton pump inhibitor, tapering once inflammatory markers subside. have typically been normalized at 400 mg per week.

If there are significant risk factors or a history of coronary heart disease, aspirin may be preferred over ibuprofen at a dose of 900 mg tds for 1 to 2 weeks, tapering by ∼600 mg per week thereafter assuming symptoms resolve and inflammatory markers normalize.

Pericarditis may recur in up to 30% of patients within 1.5 years, and in approximately 55% of those with a previous recurrence.

Adjuvant use of colchicine in acute pericarditis for 3 months at a dose of 500 μg twice daily (bd) for those >70 kg and 500 μg once daily if <70 kg increases the remission rate by 1 week and Most importantly, it more than halves the risk of recurrent or incessant pericarditis (number needed to treat = four).

Colchicine, while safe when used appropriately, has a narrow therapeutic index and therefore special attention should be paid when prescribing to potential drug interactions and comorbidities that may influence the pharmacokinetics of the drug.

Corticosteroids should be avoided if possible, unless there is a clear underlying autoimmune rheumatic disease or a contraindication to NSAIDs/colchicine, e.g. pregnancy.

While initially effective, steroid use may promote recurrence and may attenuate the effectiveness of colchicine if used first-line. The reasons for this are unclear, but it is believed that most cases of acute idiopathic pericarditis are of viral origin and that steroid use may promote viral replication and delay clearance, thus maintaining the trigger for inflammation.

For idiopathic pericarditis , they should only be used as an adjunct after a trial of NSAIDs and colchicine for patients with recurrent disease. Doses higher than 0.2-0.5 mg/kg/day of prednisolone are not required and increase the risk of side effects without additional efficacy.

Treatment is continued for 4 weeks and if symptoms resolve and inflammatory markers normalize, doses are gradually reduced by 5-10 mg/day every week until reaching 25 mg and then by 2.5 mg/day every 2 weeks. weeks until reaching 15 mg. The risk of symptom flare is greatest below 15 mg, so tapering is reduced to 1 to 2.5 mg/day every 2 to 6 weeks thereafter. When medication is tapered, colchicine should be the last drug to be withdrawn.

Recurrences may present with chest pain alone without other cardinal features of pericarditis, particularly when the inflammation has only been partially treated . In this context, cardiovascular MRI may be deficient. value to confirm ongoing inflammation.

For patients who do not achieve remission with first-line (NSAID plus colchicine) or second-line (NSAID plus steroid plus colchicine) approaches, third-line therapeutic options include azathioprine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and anakinra (an interleukin 1β antagonist). ). Azathioprine is best used as a steroid-sparing agent (typically at 1 to 3 mg/kg/day) and may take up to 3 months to be effective.

The effect of intravenous immunoglobulin is more immediate, but its availability is restricted and the evidence for its use is limited to isolated case reports and small case series. However, taking into account the possibility of publication bias, it appears to have high efficacy with an excellent safety profile.

There are some promising initial data for anakinra (2 mg/kg/day up to 100 mg) in patients with >3 recurrences. , increased inflammatory markers, resistance to colchicine and dependence on steroids. This may be consistent with the critical role that interleukin-1 plays in the innate immune response, as exemplified by patients with inherited autoinflammatory syndromes.

Surgical pericardiectomy is the treatment of last resort, although it is rarely required in clinical practice and is usually more necessary for patients with a history of cardiac surgery and/or features of constriction than for uncomplicated idiopathic recurrent pericarditis.

Prognosis and complications

The prognosis of acute idiopathic pericarditis is generally excellent with a very low risk of long-term sequelae such as constriction (<0.5%). The probability of the latter is related to the etiology of pericarditis rather than the number of episodes.

Pericaric constriction presents with signs and symptoms of heart failure (shortness of breath, fatigue, edema/ascites) but with a normal ejection fraction on echo and often a normal or minimally elevated brain natriuretic peptide. Constriction is more likely to occur after pericarditis triggered by tuberculosis/bacterial infection, trauma, and cardiac surgery.

The prognosis of myopericarditis mirrors that of pericarditis given the extensive overlap in etiology, particularly when left ventricular function is preserved.

Conclusions Acute pericarditis is a relatively common cause of acute chest pain that can be easily evaluated by a complete history complemented by ECG and echocardiography. In the developed world, the majority of cases are idiopathic and while the prognosis with respect to the development of adverse sequelae is excellent, acute episodes and recurrences can have a significant impact on the quality of life and well-being of patients. Although the study of pericardial diseases does not receive the same degree of attention as acute coronary syndromes, there is an emerging evidence base for the treatment of idiopathic acute pericarditis. The use of colchicine significantly reduces the chances of recurrence, but despite this, there remains a problematic subgroup of patients who experience multiple recurrences. For this subgroup, there is some promising initial data for the interleukin-1β antagonist anakinra. However, our understanding of the immunopathology and pathogenesis of this pericardial syndrome remains incomplete and more work is required to address this if further therapeutic advances are to be achieved. |