Key points Cancer screening is promoted to save lives , but how much life is prolonged by commonly used cancer screening? Findings In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 long-term randomized clinical trials involving 2.1 million people, screening for colorectal cancer with sigmoidoscopy prolonged life by 110 days , while fecal testing and mammography did not prolong life. life . An extension of 37 days was observed for prostate cancer detection with prostate-specific antigen testing and 107 days for lung cancer detection with computed tomography, but estimates are uncertain. Meaning The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that screening for colorectal cancer with sigmoidoscopy can prolong life by approximately 3 months ; Lifetime gain for other screening tests seems unlikely or uncertain . |

Importance

Cancer screening is promoted to save lives by increasing longevity, but it is unknown whether people will live longer with commonly used cancer screening.

Aim

Estimate the life gained from cancer detection.

Data sources

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials with more than 9 years of follow-up that reported all-cause mortality and estimated lifespan for 6 commonly used cancer screening tests, comparing screening with no screening. detection.

The analysis included the general population. The MEDLINE and Cochrane Library databases were searched, with the last search conducted on October 12, 2022.

Study selection

Breast cancer screening mammography; colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood test (FOBT) for colorectal cancer; detection of lung cancer by computed tomography in smokers and ex-smokers; or prostate-specific antigen tests for prostate cancer.

Data extraction and synthesis

Searches and selection criteria followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. Data were extracted independently by a single observer and a pooled analysis of clinical trials was used for analyses.

Main results and measures

Life years gained through screening were calculated as the difference in life observed in the screened and non-screened groups, and absolute life gained in days with 95% CI was calculated for each screening test from meta-analysis. or single randomized clinical trials.

Results

In total, 2,111,958 people enrolled in randomized clinical trials comparing screening with non-screening using 6 different tests were eligible . Median follow-up was 10 years for computed tomography, prostate-specific antigen testing, and colonoscopy; 13 years for mammography; and 15 years for sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood testing (FOBT).

The only screening test with significant lifetime gain was sigmoidoscopy (110 days; 95% CI, 0-274 days).

There were no significant differences after mammography (0 days: 95% CI, −190 to 237 days), prostate cancer screening (37 days; 95% CI, −37 to 73 days), colonoscopy (37 days; 95% CI, −146 to 146 days), screening with fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) every year or every two years (0 days; 95% CI, −70.7 to 70.7 days) ) and lung cancer screening (107 days; 95% CI, −286 days to 430 days).

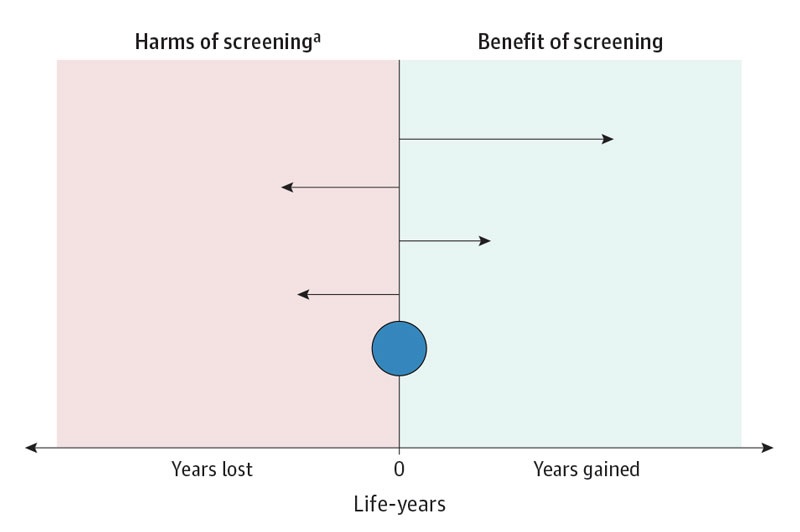

Conclusions and relevance The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that current evidence does not support the claim that common cancer screening tests save lives by prolonging life, except possibly for colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy. |

Fragment of the editorial

The Future of Cancer Detection: Guided Without Conflicts of Interest

Hans-Olov Adami, MD, PhD1,2; Mette Kalager, MD, PhD1; Michael Bretthauer, MD, PhD1

High hopes that early cancer diagnosis through screening will extend life expectancy have become increasingly controversial. Almost all trials do not include all-cause mortality as an endpoint, let alone as a primary endpoint, preventing conclusions about extending life expectancy. After much enthusiasm for cancer screening in the 1970s and early 2000s, the realization of uncertain benefits, growing concerns about overdiagnosis, and recognition of the harms of false-positive screening tests and burden of subsequent diagnostic and therapeutic procedures have made cancer detection a polarized area in contemporary medicine. It is difficult or even impossible to phase out screening programs, even when research has failed to document significant benefits. We believe that transparent, evidence-based debates on cancer screening with a delicate balance between benefits and harms have become a threat to powerful stakeholders.