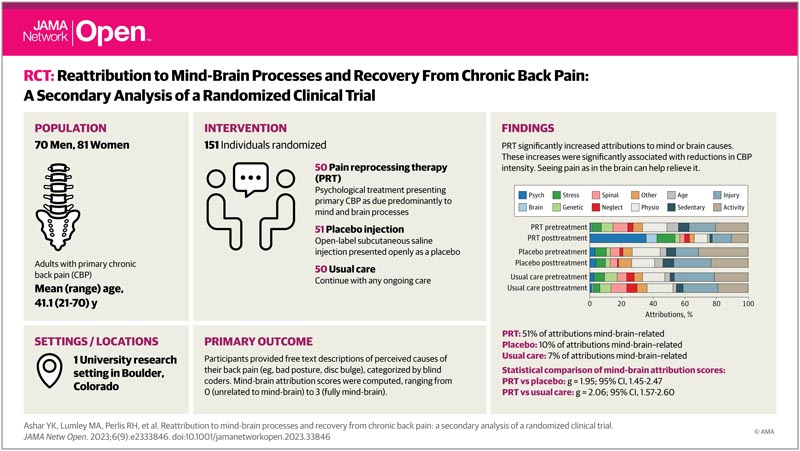

Key points Does pain reprocessing therapy , a promising psychological treatment, help patients view primary chronic pain as caused by mental or brain processes? Findings In this secondary analysis of clinical trial data, natural language methods were applied to understand patients’ beliefs about the underlying causes of their primary chronic back pain. Pain reprocessing therapy led to significant increases in mind- or brain-attributed causes of pain, and increases in mind-brain attributions were associated with reduced pain. Meaning These results suggest that patients’ pain attributions are often inaccurate and that promoting mind- or brain-related attributions may support effective treatment of primary chronic pain; Helping patients think of pain as “in the brain” can help relieve it. |

Importance

In primary chronic back pain (CBP), the belief that pain indicates tissue damage is inaccurate and unhelpful . Reattributing pain to mental or brain processes can promote recovery.

Goals

To test whether pain reattribution to mental or brain processes was associated with pain relief in pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) and to validate natural language-based tools to measure patients’ symptom attributions.

Design, environment and participants

This secondary analysis of clinical trial data analyzed natural language data from patients with primary chronic back pain (CBP) randomly assigned to PRT, placebo injection control, or usual care control groups and treated in a research setting. Eligible participants were adults aged 21 to 70 years with PBC recruited from the community. Enrollment extended from 2017 to 2018, and current analyzes were conducted from 2020 to 2022.

Pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) interventions included cognitive, behavioral, and somatic techniques to support the reattribution of pain to reversible, non-hazardous brain or mental causes. It was hypothesized that subcutaneous injection of placebo and usual care did not affect pain attribution.

Main results and measures

Before and after treatment, participants listed in their own words the top 3 perceived causes of pain (e.g., soccer injury, poor posture, stress); Pain intensity was measured as the average pain over the past week (rating from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates severe pain).

The number of attributions categorized by masked coders as reflecting mental or brain processes was summed to obtain mind-brain attribution scores (range, 0-3).

An automated scoring algorithm was developed and compared with scores derived from human coders. A data-driven natural language processing (NLP) algorithm identified the dimensional structure of pain attributions.

Results

We enrolled 151 adults (81 female [54%], 134 white [89%], mean [SD] age, 41.1 [15.6] years) who reported PBC of moderate severity (mean [SD] intensity, 4 .10 [1.26]; mean [SD] duration, 10.0 [8.9] years).

At pretreatment, 41 attributions (10%) were classified as mind- or brain-related across all intervention conditions.

PRT led to significant increases in mind- or brain-related attributions, with 71 post-treatment attributions (51%) in the PRT condition categorized as mind- or brain-related, compared to 22 (8%) in control conditions ( mind-brain ) attribution scores: PRT vs. placebo, g = 1.95 [95% CI, 1.45-2.47]; PRT versus usual care, g = 2.06 [95% CI, 1.57-2.60]).

Consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms of PRT, increases in mind-brain attribution score were associated with reductions in pain intensity after treatment (standardized β = −0.25; t 127 = −2.06; P = 0.04) and mediated the effects of PRT versus control on 1-year follow-up pain intensity (β = −0.35 [95% CI, −0.07 to −0.63]; P = 0.04). 05).

The automated word counting algorithm and the scores derived from the human coder achieved moderate and substantial agreement at pretreatment and posttreatment (Cohen κ = 0.42 and 0.68, respectively).

The data-driven NLP algorithm identified a primary dimension of mind and brain versus biomechanical attributions , converging with hypothesis-driven analyses.

Conclusions and relevance

In this secondary analysis of a randomized trial of pain reprocessing therapy (PRT), reattribution of primary chronic back pain (CBP) to mind- or brain-related causes was associated with reductions in pain intensity, with modest effect sizes.

Although the influence of various pain beliefs on chronic pain is well recognized (e.g., pain catastrophizing, pain acceptance), patients’ causal attributions of symptoms have been understudied. Pain attributions will guide important treatment decisions (e.g., surgery vs. psychotherapy) and are central to emerging neuroscientific models of brain function.

Patients’ attributions of chronic pain to tissue damage are often inaccurate, and therapeutic reattribution to brain processes may promote recovery from chronic pain.

Comments

New study provides evidence of a more effective brain treatment for chronic back pain

A new study in JAMA Network Open may provide key answers on how to help people experiencing chronic back pain.

The study examined the critical connection between the brain and pain for the treatment of chronic pain. Specifically, they looked at the importance of pain attributions , which are people’s beliefs about the underlying causes of their pain, in reducing the severity of chronic back pain.

"Millions of people experience chronic pain and many have not found ways to help with the pain, making it clear that something is missing in the way we diagnose and treat people," said the study’s first author, Yoni Ashar, PhD. . assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Ashar and his team tested whether re-attributing pain to mental or brain processes was associated with pain relief in pain reprocessing therapy (PRT), which teaches people to perceive pain signals sent to the brain. as less threatening. Their goal was to better understand how people recovered from chronic back pain. The study revealed that after PRT, patients reported a reduction in back pain intensity.

"Our study shows that discussing pain attributions with patients and helping them understand that pain is often ’in the brain’ can help reduce pain," Ashar said.

To study the effects of pain attributions, they enrolled more than 150 adults experiencing moderately severe chronic back pain in a randomized trial to receive pain reprocessing therapy (PRT). They found that two-thirds of people treated with PRT reported being pain-free or almost pain-free after treatment, compared to only 20% of placebo controls.

"This study is vitally important because patients’ pain attributions are often inaccurate. We found that very few people believed their brains had anything to do with their pain. This can be unhelpful and detrimental when trying to plan recovery , as pain attributions guide major treatment decisions, such as whether to undergo surgery or psychological treatment," Ashar said.

Before pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) treatment, only 10% of participants’ attributions to the PRT treatment were related to the mind or brain. However, after the PRT, this figure increased to 51%. The study revealed that the more participants came to view their pain as due to mental or brain processes, the greater the reduction in the intensity of chronic back pain they reported.

"These results show that changing perspectives on the brain’s role in chronic pain may allow patients to experience better outcomes," adds Ashar.

Ashar says one reason for this may be that when patients understand that their pain is due to brain processes, they learn that there is nothing wrong with their body and that the pain is a "false alarm" generated by the brain that they don’t know about. . You do not have to be afraid.

The researchers hope this study will encourage providers to talk to their patients about the reasons behind their pain and discuss causes outside of biomedical ones.

"Often, conversations with patients focus on the biomedical causes of pain. The role of the brain is rarely discussed," Ashar said. "With this research, we want to give patients the greatest relief possible by exploring different treatments, including those that address the brain drivers of chronic pain."