|

Background

Neurological and psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 have been reported, but more data are needed to adequately evaluate the effects of COVID-19 on brain health.

Our goal was to provide robust estimates of the incidence rates and relative risks of neurological and psychiatric diagnoses in patients in the 6 months following a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Methods

For this retrospective cohort study and time-to-event analysis, we used data obtained from the TriNetX electronic health records network (with more than 81 million patients).

Our primary cohort was composed of patients who had a diagnosis of COVID-19; one matched control cohort included patients diagnosed with influenza and the other matched control cohort included patients diagnosed with any respiratory tract infection, including influenza, in the same period. Patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 or a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 were excluded from the control cohorts.

All cohorts included patients older than 10 years who had an index event on or after January 20, 2020, and who were still alive on December 13, 2020.

We estimated the incidence of neurological and psychiatric outcomes in the 6 months following a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis:

- intracranial hemorrhage

- Ischemic stroke

- Parkinsonism

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Disorders of nerves, nerve roots and plexuses, myoneural junction and muscle disease.

- Encephalitis

- Dementia

- Psychotic, mood and anxiety disorders (grouped and separated).

- Substance use disorder

- Insomnia.

Using a Cox model, we compared incidences with those of propensity score-matched cohorts of patients with influenza or other respiratory tract infections. We investigated how these estimates were affected by COVID-19 severity, represented by hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and encephalopathy (delirium and related disorders).

We assessed the robustness of differences in results between cohorts by repeating the analysis in different settings. To provide a comparative assessment of the incidence and risk of neurological and psychiatric sequelae, we compared our primary cohort with four cohorts of patients diagnosed in the same period with additional index events: skin infection, urolithiasis, large bone fracture, and embolism. pulmonary.

Results

Among 236,379 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, the estimated incidence of a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis in the following 6 months was 33·62% (95% CI 33·17–34·07), with 12·84% (12·36 -13 · 33) receiving his first diagnosis of this type.

For patients who had been admitted to an ICU, the estimated incidence of a diagnosis was 46·42% (44·78–48·09) and for a first diagnosis it was 25·79% (23·50–28·09). 25).

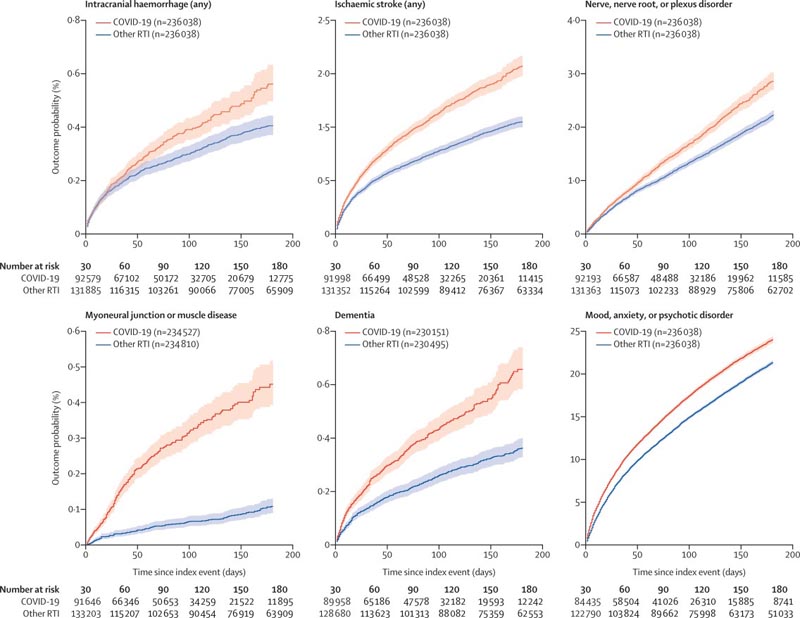

Regarding individual diagnoses from the study results, the entire COVID-19 cohort had estimated incidences of 0·56% (0·50–0·63) for intracranial hemorrhage, 2·10% (1·97–2 23) for stroke, 0 11% (0 08–0 14) for parkinsonism, 0 67% (0 59–0 75) for dementia, 17 39% (17 04– 17 · 74) for anxiety disorder and 1 · 40% (1 · 30–1 · 51) for psychotic disorder, among others.

In the ICU admission group, the estimated incidences were 2·66% (2·24–3·16) for intracranial hemorrhage, 6·92% (6·17–7·76) for ischemic stroke, 0·92% (6·17–7·76) for ischemic stroke, 26% (0 15–0 45) for parkinsonism, 1 74% (1 31–2 30) for dementia, 19 15% (17 90–20 48) for anxiety disorder and 2 77% (2·31-3·33) for psychotic disorder.

Most diagnostic categories were more common in patients who had COVID-19 than in those with influenza (hazard ratio [HR] 1 44, 95% CI 1 40–1 47, for any diagnosis; 1 78, 1 68–1 89, for any first diagnosis) and those who had other respiratory tract infections (1 16, 1 14–1 17, for any diagnosis; 1 32, 1 · 27–1 · 36, for any first diagnosis).

As with incidences, HRs were higher in patients who had more severe COVID-19 (e.g., those admitted to the ICU compared to those who were not: 1·58, 1·50– 1 · 67, for any diagnosis; 2 · 87, 2 · 45–3 · 35, for any first diagnosis).

The results were robust to several sensitivity analyzes and benchmarking against the four additional index health events.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for the incidence of important outcomes after COVID-19 compared to other RTIs

Interpretation

Our study provides evidence of substantial neurological and psychiatric morbidity in the 6 months following COVID-19 infection.

The risks were higher, but were not limited to patients who had severe COVID-19.

This information could assist in service planning and identification of research priorities.

Complementary study designs, including prospective cohorts, are needed to corroborate and explain these findings.

Research in context We searched for studies in English on Web of Science and Medline on August 1 and December 31, 2020. We found case series and series reviews reporting on neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders during acute COVID-19 illness. We found a large electronic medical record study of psychiatric sequelae in the 3 months after COVID-19 diagnosis. Reported increased risk of anxiety and mood disorders and dementia after COVID-19 compared to a variety of other health events; The study also reported the incidence of each disorder. We are not aware of any large-scale data regarding the incidence or relative risks of neurological diagnoses in patients who had recovered from COVID-19. Added value of this study To our knowledge, we provide the first significant estimates of the risks of major neurological and psychiatric conditions in the 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis, using the electronic medical records of more than 236,000 COVID-19 patients. We report their incidence and hazard ratios compared with patients who had had influenza or other respiratory tract infections. We demonstrated that both the incidence and risk ratios were higher in patients who required hospitalization or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and in those who presented encephalopathy (delirium and other altered mental states) during the illness compared to that they didn’t do it. Implications of all available evidence

Given the size of the pandemic and the chronicity of many of the diagnoses and their consequences (e.g., dementia, stroke, and intracranial hemorrhage), substantial effects on health and social care systems are likely. Our data provide important evidence indicating the scale and nature of services that may be required. The findings also highlight the need for better neurological follow-up of patients who were admitted to the ITU or who had encephalopathy during their COVID-19 illness. |

Discussion

Several adverse neurological and psychiatric outcomes occurring after COVID-19 have been predicted and reported. The data presented in this study, from a large network of electronic health records, support these predictions and provide estimates of the incidence and risk of these outcomes in patients who had COVID-19 compared to matched cohorts of patients with other health conditions. health that occur simultaneously with illness.

The severity of COVID-19 had a clear effect on subsequent neurological diagnoses. Overall, COVID-19 was associated with an increased risk of neurological and psychiatric outcomes, but the incidence and heart rate of these were higher in patients who had required hospitalization, and notably in those who had required admission to the ITU or had developed encephalopathy, even after extensive propensity score matching for other factors (eg, age or previous cerebrovascular disease). Possible mechanisms of this association include viral invasion of the CNS, hypercoagulable states, and neuronal effects of the immune response.

However, the incidence and relative risk of neurological and psychiatric diagnoses also increased even in COVID-19 patients who did not require hospitalization.

Some specific neurological diagnoses deserve individual mention. Consistent with several other reports, the risk of cerebrovascular events (ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage) rose after COVID-19, with the incidence of ischemic stroke increasing to nearly one in ten (or three in 100 for a first stroke) in patients with encephalopathy. A similar increased risk of stroke has been reported in patients who had COVID-19 compared to those who had influenza.

Our previous study reported preliminary evidence of an association between COVID-19 and dementia . The data from this study support this association. Although the estimated incidence was modest in the entire COVID-19 cohort, 2·66% of patients over 65 years of age and 4·72% who had encephalopathy, received a first diagnosis of dementia within 6 months of having had COVID-19.

The associations between COVID-19 and cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diagnoses are concerning, and information on the severity and subsequent course of these diseases is required.

It is unclear whether COVID-19 is associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Our data were also equivocal, as HRs increased with COVID-19 compared to other respiratory tract infections but not influenza and increased compared to three of the other four index health events. Concerns have also been raised about post-COVID-19 parkinsonian syndromes, driven by the encephalitis lethargica epidemic that followed the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Our data support this possibility, although the incidence was low and not all CFs were significant. Parkinsonism may be a late outcome, in which case a clearer signal may emerge with longer follow-up.

The findings regarding anxiety and mood disorders were generally consistent with 3-month outcome data from a study conducted on a smaller number of cases than our cohort, using the same network, and showed that HR remained high, although decreasing, over the 6-month period.

Unlike the previous study, and consistent with previous suggestions, we also observed a significantly increased risk of psychotic disorders , likely reflecting the larger sample size and longer duration of follow-up reported here.

Substance use disorders and insomnia were also more common in COVID-19 survivors than in those who had influenza or other respiratory tract infections (except for the incidence of a first substance use disorder diagnosis after COVID -19 compared to other respiratory tract infections).

Therefore, as with neurological outcomes, the psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 appear widespread and persist up to, and likely beyond, 6 months.

Compared with neurological disorders, common psychiatric disorders (mood and anxiety disorders) showed a weaker relationship with COVID-19 severity markers in terms of incidence. This could indicate that its appearance reflects, at least in part, the psychological and other implications of a COVID-19 diagnosis rather than being a direct manifestation of the disease.

The FCs for most neurological outcomes were constant and therefore the risks associated with COVID-19 persisted up to the 6-month time point. Longer-term studies are needed to determine the duration of risk and the trajectory of individual diagnoses.

Our findings are robust given the sample size, propensity score matching, and the results of the sensitivity and secondary analyses. However, they have weaknesses inherent to an electronic health record study, such as unknown completeness of records, lack of validation of diagnoses, and limited information on socioeconomic and lifestyle factors.

These issues primarily affect incidence estimates, but the choice of cohorts with which to compare COVID-19 outcomes influenced the magnitude of the HRs. Discussions on encephalopathy (delirium and related conditions) merit a note of caution. Even among patients who were hospitalized, only about 11% received this diagnosis, while much higher rates would be expected.

The underreporting of delirium during acute illness is well known and probably means that diagnosed cases had prominent or sustained features; as such, the results for this group should not be generalized to all COVID-19 patients experiencing delirium.

We also observed that encephalopathy is not only a marker of severity, but a diagnosis in itself, which could predispose or be an early sign of other neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative outcomes observed during follow-up.

The timing of the index events was such that most influenza infections and many of the other respiratory tract infections occurred earlier during the pandemic, while the incidence of COVID-19 diagnoses increased over time. The effect of these temporal differences on the observed rates of sequelae is unclear, but if anything, they likely underestimate the HRs because COVID-19 cases were diagnosed at a time when all other diagnoses were made at a lower rate. lowest in the population.

Some patients in the comparison cohorts are likely to have had undiagnosed COVID-19; This would also tend to underestimate our human resources. Finally, such a study can only show associations; Efforts to identify mechanisms and assess causality will require prospective cohort studies and additional study designs.

|