| Highlights |

• The spectrum of clinical implications of premature ventricular complex (PVC) is broad, ranging from being completely benign to the development of cardiomyopathy and heart failure, and may be associated with an increased risk of sudden death. • PVCs can be both a cause and a consequence of undiagnosed cardiomyopathy and progression of congestive heart failure. • In patients with a high PVC burden (>10%), electrocardiogram, ultrasound, Holter monitoring, and echocardiography are critical in evaluating features that help guide future management decisions. • Management of symptomatic PVCs, high-risk PVCs from sudden cardiac death, or a high burden of PVCs causing cardiomyopathy includes medical therapy and catheter ablation. |

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are defined by early electrical activation from a focal region of the ventricle, leading to ventricular contraction before coordination and adequate filling of these chambers.

The clinical significance of PVCs ranges from being completely benign to life-threatening.

A significant proportion of patients have PVCs with practically no clinical significance; However, there are a considerable number of patients in whom PVCs may represent an underlying cardiomyopathy or a propensity for the development of heart failure. Some PVCs may also increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and sudden cardiac death.

Risk factors include older age, male sex, smoking and obesity. Given its frequency in clinical practice, it is imperative that the primary care physician has knowledge of the pathophysiological mechanism, the necessary studies, and the treatment of PVCs. Additionally, the general practitioner must be able to distinguish benign from malignant PVCs and know when to seek expert consultation.

| Pathophysiology |

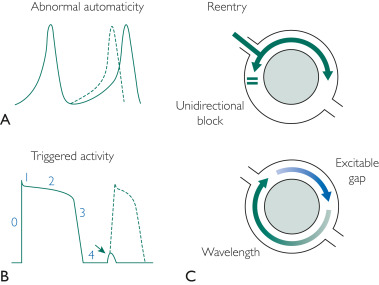

Three main mechanisms are used to explain PVC generation: triggered activity, enhanced automaticity, and reentry.

The triggered activity is mediated by an increase in intracellular calcium concentration, resulting in delayed afterdepolarizations or abnormal depolarization of cardiac myocytes after normal depolarization.

Enhanced automaticity occurs when certain myocardial tissues exhibit enhanced or exaggerated automatic generation of cardiac electrical impulses. Reentry as a mechanism requires 2 separate and distinct electrical pathways with differential conduction at each extremity. Regions of scarring and fibrosis (e.g., resulting from coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies) may cause PVCs to have a reentry mechanism ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1 . Three mechanisms of premature arrhythmogenesis of the ventricular complex. A, abnormal automaticity: note the early onset of the action potential (dotted line). B, Triggered activity: note the delay in afterdepolarization that occurs in phase 4 of the cardiac action potential. If this reaches threshold, complete depolarization can occur (dotted line). This is just one example of the triggered activity mechanism. C, Reentry: conduction barrier (gray circle, representing fibrosis or functional barrier) with unidirectional block that produces a reentry arrhythmia.

| Electrical timing and associated hemodynamic changes |

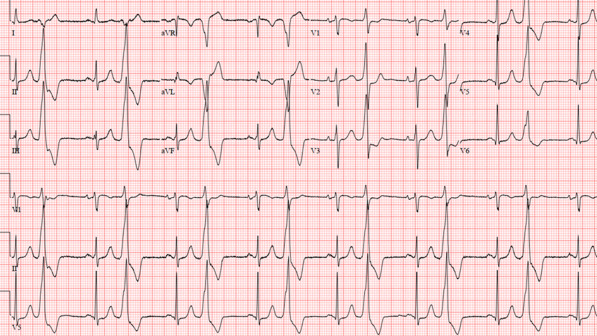

A PVC disrupts the normal filling of the ventricles. In addition to the QRS complex (representing ventricular contraction) occurring earlier than expected, PVCs generally have a wider QRS appearance (longer duration) on the ECG compared to a typical QRS complex seen in sinus rhythm ( Figure 2 ).

Premature ventricular complexes originate from focal electrical impulses coming from different sites in the ventricles. In contrast to a normal rhythm, electrical conduction with a CVP generally does not use the specialized conduction system.

FIGURE 2. Premature ventricular complexes with bigeminal pattern. Note the wide complex beats that occur every other sinus beat (narrow QRS, preceded by the p wave). These premature ventricular contractions have a prominent inferior axis (positive II, III, and aVF and negative aVR and aVL), likely signifying an outflow tract origin.

Because diastolic filling of the ventricle is disrupted, this results in reduced ventricular filling. Thus, cardiac output resulting from PVC-related ventricular contraction decreases. It can cause patients to experience a host of symptoms, including shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and fatigue. Additionally, left atrial pressures may be significantly elevated, causing dyspnea due to higher pulmonary pressures.

| Clinical evaluation and natural history of CVP |

The clinical presentation of PVCs can be varied. The majority, particularly those with low burden, are asymptomatic in up to 50 to 75% of patients. For those in whom symptoms occur, the most common manifestations include extrasystoles, palpitations, and prominent heartbeats with a pounding sensation.

In the case of more frequent and hemodynamically significant PVCs, patients may complain of fatigue, dizziness, presyncope, and symptoms of heart failure, such as dyspnea, orthopnea, and edema.

At the extreme, patients with electrophysiologically significant PVCs may present with syncope and sudden cardiac arrest.

In this context, a careful clinical history must be obtained to differentiate the causes of syncope. Vasovagal (reflex) syncope, which portends a more benign clinical course, usually presents with a precipitating factor or event (eg, dehydration) and preceding symptoms (eg, nausea, diaphoresis). Cardiogenic or arrhythmogenic syncope appears suddenly and without warning and may be associated with exertion.

Family history should include screening for heart failure, coronary artery disease, arrhythmias, history of cardiomyopathy, and sudden, unexplained deaths, especially in young family members. The social history should include a detailed description of caffeine intake, alcohol use, supplements, drug use, and psychological stressors. Activities such as exercise and sports participation should also be evaluated.

Medications that can trigger CVP include beta-agonists (such as albuterol inhalers for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), alcohol, caffeine, and stimulants such as those derived from amphetamines. Cardiac auscultation is essential. Clinical signs of heart failure should be evaluated and evaluated.

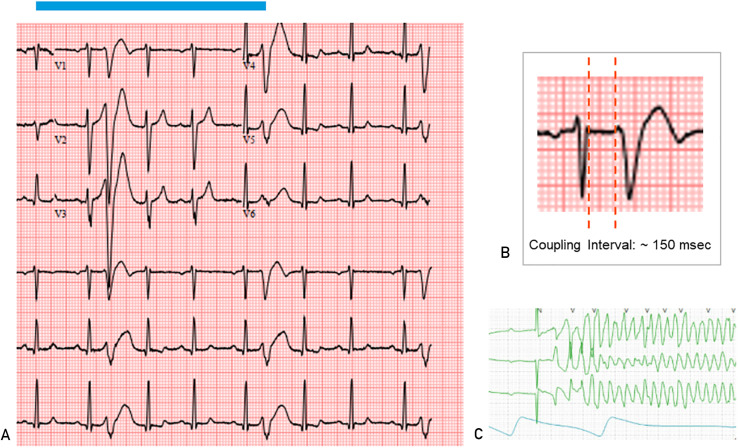

The patient’s medical history, PVC morphology (which allows localization of its origin in the heart), PVC coupling intervals (the duration between the end of the previous QRS and the beginning of the PVC), and blood pressure load are monitored. CVP for 24 hours is essential to determine appropriate management.

Some patients may have a low CVP burden but have serious consequences (such as sudden cardiac death) if the coupling interval is less than 300 milliseconds. Therefore, there must always be a high level of surveillance to ensure proper evaluation ( Figure 3 ).

FIGURE 3 . A, Electrocardiogram showing a short-coupled premature ventricular complex (CVP). Note that these short-coupled PVCs fall on the T wave of the preceding sinus beat. B, PVC coupling interval measurement should be taken at the end of the anterior QRS and the beginning of the PVC. C, Telemetry strip showing polymorphic ventricular tachycardia triggered by a closely coupled PVC in the same patient.

Specifically, the internist should focus on the following characteristics to refer to a cardiologist: PVC symptoms, suspected cardiac syncope, family history of sudden death, PVC burden greater than 10%, and short-coupled PVC (coupling interval <300 milliseconds). ).

| Tailored Diagnostic Testing Strategy for CVP |

In the primary care setting, the depth of diagnostic testing should be carefully tailored to the clinical suspicion after the medical history has been obtained and the physical examination has been performed. In almost all healthy, asymptomatic patients without known or suspected cardiac disease, the initial ECG is reasonable. If symptoms are present, or examination or electrocardiogram reveals concern for an increased CVP burden (>1 in 10 beats), Holter monitoring should be performed for a 24-hour evaluation.

> Electrocardiography and Holter monitoring

In ECG and Holter monitoring, the clinician should consider the following: PVC burden (usually presented as a percentage over a period of time); Morphology and axis of the PVC to help locate the site of origin; CVP coupling interval; and, most importantly, if the patient presents symptoms, correlation of the PVCs at the exact moment of the symptoms.

> Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography should be considered in patients with a PVC burden greater than 5% or if clinically indicated by history and physical examination. In particular, clinicians should look for reduced left ventricular systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction <50%) or signs of left or right ventricular enlargement and dysfunction, especially if they are greater than mild.

Valvular disease , such as mitral valve prolapse or mitral annulus disjunction, should also be considered . Cardiac structural abnormalities may portend additional arrhythmic or cardiomyopathic risk for PVCs originating in this region and should therefore be referred to a cardiologist if present.

> Additional tests

Additional testing should be guided by history and clinical suspicion after the study has been obtained. Laboratory studies should, at a minimum, include evaluation of serum electrolyte values , particularly potassium and magnesium. In general, the serum potassium concentration should be maintained above 4.0 mEq/L and the serum magnesium concentration should be maintained above 2.0 mEq/L.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone should be monitored to rule out thyroid disease as a secondary cause of PVC.

Brain natriuretic peptide can be tested as a possible serological marker of cardiac structural abnormality.

Stress testing , with and without additional cardiac imaging (such as stress echocardiography or nuclear perfusion stress testing), may be considered to rule out ischemic heart disease if clinically indicated.

Advanced cardiac imaging, such as cardiac MRI to evaluate various cardiomyopathies and cardiac positron emission tomography to evaluate active inflammation, such as cardiac sarcoidosis, should generally be performed under the guidance of cardiology specialists. These tests are generally not performed routinely without a cardiology referral.

| Therapies for CVP |

Most patients with PVC, especially with low burden, are asymptomatic and do not require additional studies, therapy, or follow-up.

The primary care physician should be comfortable with the basic principles of PVC management, including when to initiate treatment, appropriate follow-up testing, and when to refer for cardiology consultation.

> Non-pharmacological advice and management

It is important to ask patients how bothersome their symptoms are and whether, after reassurance, they would even want to try medical or catheter ablation therapy, given the potential risks and adverse effects in an otherwise benign condition. Additionally, although there are no definitive studies linking PVCs with these lifestyle habits, moderating caffeine and alcohol consumption, as well as quitting smoking, is reasonable advice.

In general, the authors recommend that all patients exercise a minimum of 30 minutes a day for 5 days a week. Patients are often concerned about this and should be reassured that exercising is safe. If they have a clear worsening of symptoms with exercise, additional studies, such as stress testing, should be considered.

> Medical therapy

The mainstays of pharmacological treatment are beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem or verapamil). Of note, some patients cannot tolerate these medications due to adverse effects, such as fatigue, depression, and erectile dysfunction. In such patients, if there is a high frequency of PVC, symptoms that correlate with PVC, PVC-induced heart failure, or arrhythmias, early referral to a cardiac electrophysiologist should be sought to consider catheter ablation.

Beta -blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are first-line pharmacological treatments. Both medications have been associated with clinically significant reductions in PVC burden in approximately 12% to 24% of patients in randomized controlled trials, indicating the somewhat limited efficacy of drug treatment.

If beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are ineffective, other antiarrhythmics may be considered if the patient is hesitant about catheter ablation. Sotalol (class III antiarrhythmic), flecainide (class Ic antiarrhythmic), and propafenone (class Ic antiarrhythmic) may be well tolerated and effective. Amiodarone is a very effective medication, but it has the potential to cause long-term adverse effects that limit its use in younger patients.

> Catheter ablation

Catheter ablation is an invasive but effective method of treating PVCs, with procedural success rates of 80% to 95%. In the most recent expert consensus statements, medications and catheter ablation can be considered first-line therapies. Therefore, the decision to perform a catheter ablation procedure directly can be discussed with patients who are hesitant about taking long-term drugs or who have previously not responded to medications due to adverse effects and intolerance.

| Future Directions |

Improvement in PVC detection using wearable devices can be expected in the near future.

Currently, a general rule is that the clinician should always manually examine the rhythm strips for arrhythmias detected by the device to avoid overdiagnosis of artifacts that frequently accompany plethysmography.

Technology should always remain a complement, not a substitute, for clinical judgment.

| Conclusion |

As more patients with PVC are identified, it is critical that the primary care physician be familiar with the fundamentals of diagnosis and treatment. PVCs are extremely common in the general population and most do not require additional studies or treatments, the recognition of which avoids unnecessary further tests.

Clinicians should also be alert for symptomatic PVCs or high-risk features, including a PVC burden greater than 10%, family history of sudden death, cardiogenic syncope, short-coupled PVCs (coupling interval <300 milliseconds), and signs and symptoms of heart failure.

Pharmacologic treatment with beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers may be attempted, and referral to a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist is warranted to initiate treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation.