“Of course it’s happening inside your head, Harry, but what the hell does that mean it’s not real then? (Harry Potter, JK Rowling)

In a population-based study conducted in Sweden and published in JAMA Network Open , a team of scientists found that people diagnosed with hypochondriasis , commonly known as health anxiety disorder , face a significantly increased risk of death compared to those without the condition. . This study, the first of its kind, indicates an increased likelihood of death from natural and unnatural causes, particularly suicide .

The study highlights the challenges and complexities surrounding hypochondria. Characterized by excessive worry about having one or more serious illnesses, this condition often leads to a catastrophic interpretation of bodily symptoms, resulting in excessive health-related anxiety.

Key points Are people with hypochondria at higher risk of death due to natural and unnatural causes? Findings In this Swedish nationally matched cohort study of 4,129 people with a diagnosis of hypochondria and 41,290 demographically matched people without hypochondria, those with hypochondria had an increased risk of death from both natural and unnatural causes, particularly suicide. Meaning This study suggests that people with hypochondria have a higher risk of mortality, mainly from potentially preventable causes. |

Hypochondria, also known as health anxiety disorder, is a prevalent psychiatric disorder characterized by persistent worry about having one or more serious and progressive physical disorders. Worry is accompanied by hypervigilance and catastrophic interpretation of bodily signs, resulting in repetitive, excessive control and reassurance-seeking behavior or maladaptive avoidance. The symptoms are clearly disproportionate and cause significant discomfort and impairment.

Hypochondria is believed to be severely underdiagnosed due to its failure to be adequately recognized and taken seriously by healthcare professionals, as well as the negative connotations associated with the diagnostic label. However, as a symptom, health anxiety is highly prevalent in healthcare settings and is associated with substantial use of healthcare resources. Hypochondriasis is widely considered a chronic disorder, with a low likelihood of remission without specialized treatment.

People with hypochondria have high rates of medical consultations, which usually leads to a chain of laboratory and other tests, which are often unnecessary from a medical perspective and conceptualized as counterproductive from a psychological point of view. In theory, this high degree of surveillance can lead to early detection and timely treatment of serious health conditions, which could reduce mortality. However, there are several reasons to believe that this may not be the case.

- Firstly, some people with hypochondria experience such high levels of anxiety about their health that they actually avoid contact with medical services altogether, risking potentially serious illnesses.

- Second, chronic anxiety and depression, which are hallmarks of the disorder, are known to be associated with a variety of adverse health consequences, such as cardiovascular disorders and premature mortality. A Norwegian longitudinal cohort study of 7052 people found that those with self-reported health anxiety symptoms were 73% more likely to develop ischemic heart disease after a 12-year follow-up compared to people with low health anxiety scores. .

- Finally, suicide has not been formally investigated among people with hypochondria, but could contribute to higher mortality in this group. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with a clinical diagnosis of hypochondria.

This nationwide matched cohort study linked several Swedish registries to investigate all-cause and cause-specific mortality among a large cohort of people with hypochondria. Unlike its international version, the Swedish version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) includes separate diagnosis codes for hypochondriasis and dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphic disorder), 16 resulting in a unique resource for nationwide cohort studies.

Importance

Hypochondria, also known as health anxiety disorder, is a prevalent, yet underdiagnosed, psychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent preoccupation with having serious and progressive physical disorders. The risk of mortality among people with hypochondria is unknown.

Aim

To investigate all-cause and cause-specific mortality among a large cohort of people with hypochondria.

Design, environment and participants

This Swedish nationwide matched cohort study included 4129 people with a validated International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis of hypochondria, assigned between January 1, 1997 and December 31, 2020, and 41,290 demographically matched people without hypochondria.

Individuals with a diagnosis of dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphic disorder) assigned during the same period were excluded from the cohort. Statistical analyzes were performed between May 5 and September 27, 2023.

Exposure

Validated ICD-10 diagnoses of hypochondria in the National Patient Registry.

Main results and measures

Mortality from all causes and from specific causes in the Causes of Death Registry. Covariates included year of birth, sex, county of residence, country of birth (Sweden vs. foreign), last recorded educational level, marital status, family income, and lifetime psychiatric comorbidities. Stratified Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Results

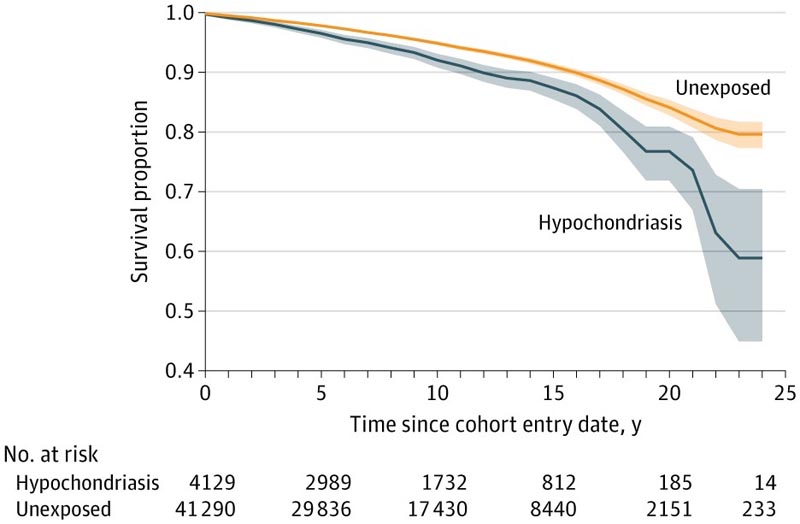

Of the 4,129 individuals with hypochondria (2,342 women [56.7%]; median age at first diagnosis, 34.5 years [IQR, 26.3-46.1 years]) and 41,290 demographically matched individuals without hypochondria (23,420 women [56.7%]; median age at matching, 34.5 years [IQR, 26.4-46.2 years]) in the study, 268 people with hypochondria and 1761 people without hypochondria died during the period study, corresponding to crude mortality rates of 8.5 and 5.5 per 1000 person-years, respectively.

In models adjusted for sociodemographic variables, a higher all-cause mortality rate was observed among individuals with hypochondria compared to individuals without hypochondria (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.47-1.93) .

An increase in the rate of both natural (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.38-1.85) and unnatural (HR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.38-1.85) causes of death was observed. 61-3,68).

Most deaths from unnatural causes were attributed to suicide (HR, 4.14; 95% CI, 2.44-7.03).

The results were generally robust to additional adjustment for lifetime psychiatric disorders.

Figure: Survival curves by exposure group.

Conclusions and relevance

This cohort study suggests that people with hypochondriasis have an increased risk of death from both natural and unnatural causes, particularly suicide, compared to people in the general population without hypochondria. Better detection and access to evidence-based care should be prioritized.

Discussion

Dismissing the somatic symptoms of these individuals as imaginary can have dire consequences.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine causes of death among people with clinically diagnosed hypochondria . Several key findings emerged.

First, people with a diagnosis of hypochondria had a significantly higher mortality rate than their counterparts without hypochondria and an 84% higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to people in the general population. The risks were broadly comparable for women and men with the disorder. The risks were largely unchanged (with slightly attenuated estimates) after adjusting for socioeconomic variables known to be associated with life expectancy. The increased risk of death was already evident at the beginning of follow-up.

Second, people with hypochondria had a higher risk of death from both natural and unnatural causes compared to people without hypochondria. Among natural causes of death, the most common were diseases of the circulatory system, respiratory diseases, and “symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified” (including primarily people whose death was due to unknown reasons ). Our study could not address the mechanisms behind the findings. It is likely that multiple factors, probably acting together, are associated with increased risks. The avoidance of medical consultations that has been described for some individuals with severe hypochondria seems a less plausible explanation, given the observation that the risk of death from malignancies was comparable in the groups with and without hypochondria. Other possible explanations seem more plausible, such as chronic stress leading to dysregulated function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immune dysfunction, chronic inflammation, lifestyle factors (e.g., alcohol and substance use). , the poor recognition of hypochondria as a true psychiatric disorder that requires treatment and/or limited access to evidence-based treatment.

Third, people with a diagnosis of hypochondria had more than four times the risk of death by suicide compared to people in the general population. To our knowledge, the risk of suicide in this group has not been previously quantified. A systematic review concluded that suicide attempts may be less frequent among people with hypochondria than among people without it, although the included studies had methodological limitations. Doctors should be aware that people with hypochondria are at risk of dying by suicide, especially if they have a lifetime history of depression and anxiety .

Fourth, the risks of death from all causes and from natural causes were higher among people who were first diagnosed in inpatient settings compared to people who were first diagnosed in outpatient settings, suggesting that patients with more severe or complex symptoms requiring hospitalization are more likely to die. The risk of death from unnatural causes was not significantly different between groups, possibly due to limited statistical power.

Fifth, systematic adjustment for lifetime psychiatric disorders attenuated the magnitude of the risks, but overall the risks remained statistically significant. Suicide risk was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for depressive and anxiety-related disorders. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the high proportion of exposed individuals with these comorbidities throughout their lives and the resulting power issues. In a post hoc analysis that limited comorbidities to those recorded before hypochondria, the risk of suicide was attenuated but remained statistically significant. Even if the finding of increased mortality were not entirely specific to hypochondria, it is clear that hypochondria is not associated with protection against death.

Together, these findings illustrate a paradox : People with hypochondria have an increased risk of death despite their pervasive fears of illness and death. In this study, the majority of deaths could be classified as potentially preventable . Dismissing the somatic symptoms of these individuals as imaginary can have dire consequences . More must be done to reduce stigma and improve screening, diagnosis, and appropriate integrated care (i.e., psychiatric and somatic) for these individuals. Evidence-based psychological treatments for hypochondriasis exist and, in some countries, are even available as low-threshold guided self-help over the Internet, substantially increasing access to treatment. The hope is that increased screening and access to evidence-based treatments will reduce somatic morbidity, suicidality, and mortality in this group.

Comments

Speaking to PsyPost , Dr David Mataix-Cols, author of the study and professor at the Karolinska Institutet Psychiatric Research Centre, said: "There was a clear gap in the literature. While the risk of death among psychiatric patients in general is Well known, there were no previous studies on hypochondria. Some old studies had even suggested that the risk of suicide may be lower in people with hypochondria, compared to unaffected people, since they have no desire to die. Our hunch, based on clinical experience, was that this would be incorrect.”

"The results may surprise some readers who are not familiar with the disorder," Mataix-Cols said. “On the surface, one might think that because they see doctors frequently, people with hypochondria may have a lower risk of death. However, doctors who work with this group of patients know that many individuals experience considerable suffering and hopelessness , which could explain the elevated risk of suicide that we describe in the article. “It is also known that experiencing high levels of stress over many years is associated with an increased risk of death.”

Final message This cohort study is the first, to our knowledge, to suggest that people with hypochondriasis have an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Excess mortality was attributed to both natural and unnatural causes, particularly suicide, which can generally be classified as preventable. |