Snacks make up nearly a quarter of daily calories for American adults and account for about a third of daily added sugar , a new study suggests.

Snacking contributes significantly to total dietary intake among adults stratified by blood glucose in the United States. Summary Little is known about snacking patterns among adults with type 2 diabetes. The contribution of snacks to energy and nutrient intake is important to better understand dietary patterns and glycemic control. The purpose of this study is to evaluate snacking among adults by diabetes status in the United States. An NHANES 24-hour dietary recall for each participant collected between 2005 and 2016 (n = 23,708) was used for analysis. Analysis of covariance was used to compare differences in nutrient and food group intake from snacks across levels of glycemic control, while controlling for age, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, and age. gender. The results of this analysis report that adults with type 2 diabetes consume less energy, carbohydrates, and total sugars from snacks than adults without diabetes. Those with controlled type 2 diabetes consumed more vegetables and less fruit juice than other groups, however, adults with type 2 diabetes generally consumed more cured meats and sausages than adults without diabetes or with prediabetes. The protein in all snacks for those without diabetes is higher than for all other groups. This study clarifies common snacking patterns among American adults with diabetes and highlights the need for clinicians and policymakers to consider snacking when assessing and providing dietary recommendations. |

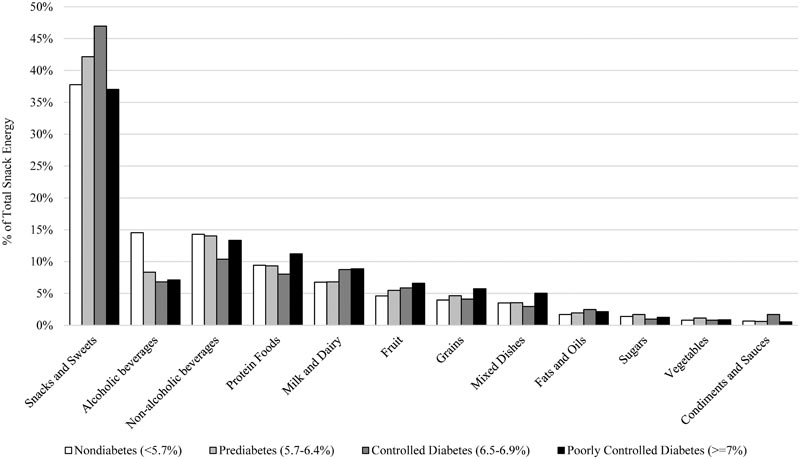

Figure: Proportion of food sources of energy consumed during snacks according to levels of glycemic control.

Comments

Researchers who analyzed survey data from more than 20,000 people found that Americans consumed on average 400 to 500 calories in snacks a day (often more than they consumed for breakfast) that offered little nutritional value.

Although dietitians are well aware of the importance of Americans’ propensity to snack, "the magnitude of the impact isn’t realized until you actually look at it," said the study’s senior author, Christopher Taylor, a professor of medical dietetics at the Ohio State University College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences.

"Snacks contribute to the meal-equivalent intake we eat without actually being a meal," he says. Taylor said. "You already know what dinner is going to be: a protein, a side dish or two. But if you eat a meal of what you snack on, it becomes a completely different scenario of, usually, carbs, sugars, little protein, little fruit, "Not a vegetable. Therefore, it is not a complete meal."

Survey participants managing their type 2 diabetes ate fewer sugary foods and snacked less overall than participants without diabetes and those whose blood sugar levels indicated they were prediabetic .

"Diabetes education appears to be working, but we may need to return education to people at risk for diabetes and even people with normal blood glucose levels to start improving eating behaviors before people develop chronic diseases," he said. ; Taylor said.

The study was recently published in PLOS Global Public Health .

The researchers analyzed data from 23,708 American adults over the age of 30 who had participated from 2005 to 2016 in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The survey collects 24-hour dietary recalls from each participant, detailing not only what, but also when all the food was consumed.

Respondents were categorized based on their HbA1c level , a measure of glucose control, into four groups: nondiabetics, prediabetes, controlled diabetes, and poorly controlled diabetes .

Among the entire survey sample, snacks represented between 19.5% and 22.4% of total energy intake, although they provided very little nutritional quality. In descending order of proportion, the snacks consisted of prepared foods rich in carbohydrates and fats, sweets, alcoholic beverages, non-alcoholic beverages including sugary drinks, proteins, milk and dairy products, fruits, cereals and, far behind, vegetables.

Noting that capturing 24 hours of food consumption doesn’t necessarily reflect how people typically eat, "it gives us a very good snapshot of a large number of people," he said. Taylor said. "And that can help us understand what’s going on, where the nutritional gaps might be, and the education we can provide."

Finding that people with diabetes had healthier snacking habits was an indicator that diet education is beneficial for people with the disease. But it’s information almost everyone can use, Taylor said, and it’s about more than just cutting back on sugar and carbohydrates.

"We need to move from consuming less added sugar to healthier snacking patterns," she said. "We’ve gotten to the point of demonizing individual foods , but we have to look at the big picture." Eliminating added sugars will not automatically improve vitamin C, vitamin D, phosphorus and iron. And if we eliminate refined grains, we lose the nutrients that come with fortification.

"When you take something out, you have to put something back, and substitution becomes as important as removal ." And so, rather than offering advice on what foods to snack on, Taylor emphasizes looking at the total dietary picture of a day and seeing if the snacks will meet our nutritional needs.

"Especially during the holidays , it’s all about the environment and what you have available, and plan accordingly. And it’s about purchasing behavior: what do we have at home?" he said.

"We think about what we’re going to pack for lunch and what we’re going to cook for dinner. But we don’t plan our snacks that way. So you’re at the mercy of what’s available in your environment."

This work was supported by Abbott Nutrition and Ohio State. Co-authors included Kristen Heitman, Owen Kelly, Stephanie Fanelli and Jessica Krok-Schoen of Ohio State and Sara Thomas and Menghua Luo of Abbott Nutrition.