Summary

Psoriasis is a clinically heterogeneous lifelong skin disease that presents in multiple forms, including plaque, flexural, guttate, pustular, or erythrodermic.

An estimated 60 million people have psoriasis worldwide, with 1.52% of the general population affected in the UK. An immune-mediated inflammatory disease, psoriasis has a significant genetic component. Its association with psoriatic arthritis and increased rates of cardiometabolic, hepatic, and psychological comorbidity requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary care approach.

Treatments for psoriasis include topical agents (vitamin D analogues and corticosteroids), phototherapy (narrow band ultraviolet B radiation (NB-UVB) and psoralen and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA)), standard systemic (methotrexate, cyclosporine and acitretin ), biological (tumor necrosis factor). (TNF), interleukin (IL)-17, and IL-23 inhibitors) or small molecule inhibitor therapies (dimethyl fumarate and apremilast). Advances in understanding its pathophysiology have led to the development of highly effective and specific treatments.

Key points

|

Psoriasis is a lifelong immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease, associated with diseases such as psoriatic arthropathy, psychological, cardiovascular and liver diseases.

In 2014, the World Health Organization recognized psoriasis as a serious non-communicable disease and highlighted the distress related to misdiagnosis, inadequate treatment and stigmatization of this disease. -Adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2016; at least three times higher than that of inflammatory bowel disease.

Epidemiology

Psoriasis affects both men and women, with an earlier onset in women and people with a family history. Its age of onset shows a bimodal distribution with peaks at 30-39 years and 60-69 years in men, and 10 years earlier in women.

An estimated 60 million people have psoriasis worldwide, with country-specific prevalence varying between 0.05% of the general population in Taiwan and 1.88% in Australia. It is more common in high-income areas and those with older populations. In the United Kingdom, it affects 1.52% of the general population.

Etiology

The pathogenesis of psoriasis is multifactorial, with genetics being a major contributor, especially in those with early-onset plaque psoriasis (<40 years). This was demonstrated through twin, familial, and large-scale population-level studies, with heritability estimated at 60-90%.

More than 60 susceptibility loci have now been identified through genome-wide association studies.5 Many of the candidate causal genes are involved in antigen presentation (HLA-C and ERAP1), NF-kappa B signaling ( TNIP1), the type 1 interferon pathway (RNF113 and IFIH1), the interleukin (IL)-23/Th17 axis (IL23R, IL12B and TYK2) and skin barrier function (LCE3).

This suggests a complex interplay between T cells, dendritic cells and keratinocytes as the likely underlying cause of psoriasis pathophysiology, with the IL-23/Th17 axis being the central driver of immune activation, keratinocyte proliferation.

Environmental triggers are known to exacerbate psoriasis, such as obesity, stress, beta blockers, smoking, and lithium.

Although there is a relative paucity of data, pustular psoriasis appears to be genetically distinct, with different susceptibility genes implicated (IL36RN, AP1S3 in those of European ancestry, and CARD14).

Clinical presentations

Psoriasis manifests itself in several ways:

- plaque psoriasis

- flexural

- guttata

- pustular or erythrodermic

The most common form is plaque psoriasis , which presents as well-circumscribed salmon-pink plaques with silvery-white scales, typically in a symmetrical distribution and affecting the extensor surfaces (especially elbows and knees), trunk, and scalp. (Fig 1). Bleeding points can be seen where the scales have been removed (Auspitz sign).

Chronic plaque psoriasis. Erythematous, scaly, disseminated plaques, symmetrically distributed and well delimited. Extensor surfaces, such as the elbows and knees, are often affected.

Flexion psoriasis occurs without much scaling and can affect the axillary, submammary, and genital areas.

Guttate psoriasis causes an acute symmetrical eruption of teardrop-shaped papules/plaques primarily affecting the trunk and extremities, which is classically, but not always, preceded by streptococcal infection. Patients with guttate psoriasis may later develop plaque psoriasis.

In rare cases of severe uncontrolled disease, psoriasis causes a generalized erythematous rash (erythroderma) that is life-threatening due to potential complications including hypothermia, risk of infection, acute kidney injury, and high-output heart failure. The Koebner phenomenon describes the appearance of psoriasis in areas of the skin affected by trauma.

The nails may be affected in up to 50% of patients and may manifest as nail pitting (nail cleavage), onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), oil stains (discoloration of the nail bed), subungual dystrophy and hyperkeratosis.

Multimorbidity and psoriasis

Defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions, multimorbidity is common in people with psoriasis. Psoriatic arthritis ( PsA) affects up to 30% of patients with psoriasis, being more common in those with nail dystrophy and scalp/intergluteal/perianal psoriasis.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease that can present as a seronegative asymmetric oligoarthropathy, enthesitis or dactylitis. In most patients, psoriasis precedes joint disease by up to 10 years. Therefore, GPs and dermatologists caring for patients with psoriasis are in a good position to make an early diagnosis of PsA.

People with psoriasis are more likely to suffer from obesity, cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome than the general population, and rates are especially high in those with more severe psoriasis.

This may be related to shared genetic factors. genetic traits, pathogenic inflammatory pathways and common risk factors.

The consequence is a high mortality rate in patients with severe psoriasis, mainly due to cardiovascular causes. This is potentially modifiable, and aggressive treatment of psoriasis has been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Additionally, rates of mental health disorders (such as anxiety and depression) are also high compared to the general population, highlighting the psychosocial impact of psoriasis.

Evaluation of patients with psoriasis

Psoriasis is evaluated by the degree of skin involvement (body surface area (BSA)) and the severity of erythema, induration, and scaling. In secondary care, validated scores such as the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) and the Physician Global Assessment Scale are routinely used alongside patient-reported outcome measures such as the Quality Index. life in dermatology (DLQI).

Attention to its psychological impact is essential as this can contribute to disengagement and non-compliance with therapy. Each patient encounter is also an opportunity to detect multimorbidities.

In addition to improving overall health, recognition of multimorbidities may influence the choice of psoriasis treatment. For example, chronic liver disease may contraindicate the use of methotrexate. A multidisciplinary approach is therefore crucial and often involves rheumatologists, hepatologists and clinical psychologists.

Treatment for psoriasis

Therapeutic options for psoriasis include topical therapy, phototherapy or systemic treatment, and are summarized in the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. Treatment goals include at least 75% or 90% improvement in PASI (PASI75 or PASI90), resulting in absolute PASI scores of ≤4 or ≤2, respectively.

Topical therapies such as vitamin D analogues (calcipotriol) or corticosteroids are first line. The effectiveness of topical treatment can be increased with occlusion or combination therapy (eg, calcipotriol/betamethasone). The previously popular dithranol and tar preparations are used less frequently as they stain and irritate the skin.

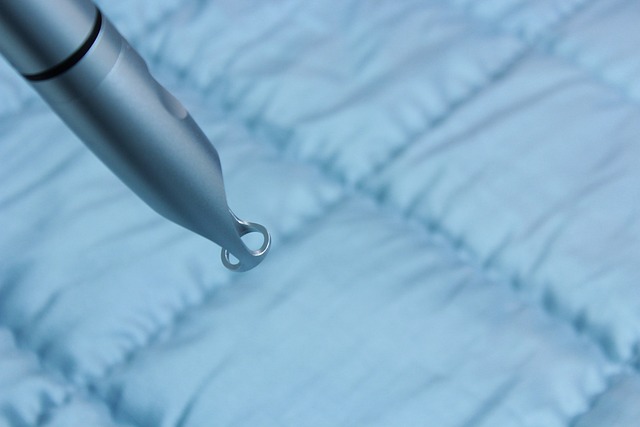

Psoriasis in difficult-to-treat areas (scalp, face, nails, genitals, palms, and soles) deserves special attention due to its profound impact on function and its relatively poor response to treatment (Fig. 2). Use of steroids for the face or genitals should be low potency and limited to short-term use due to the risk of skin atrophy and telangiectasia.

Psoriasis affecting the palms. Psoriasis on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, scalp, face, nails and genitals is difficult to treat and can have a profound impact on activities of daily living.

Second-line therapy includes phototherapy (narrow-band ultraviolet B radiation (NB-UVB) and psoralen with ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA)) and conventional systemic agents (methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin). NB-UVB has largely replaced PUVA due to skin cancer risks with cumulative doses of PUVA.

Methotrexate acts by inhibiting lymphocytes through multiple mechanisms including inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase, blockade of aminoimidazole carboxamide ribotide transformylase (AICARTase), and accumulation of adenosine . Its most serious adverse effect is bone marrow suppression. Other possible complications of treatment include nausea, pneumonitis, hepatitis, liver fibrosis, and teratogenicity. Methotrexate is usually taken by mouth every week. The subcutaneous formulation causes fewer gastrointestinal side effects and is more effective due to its greater bioavailability.

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor and has a rapid onset of action, but can cause hypertension and irreversible renal toxicity . Acitretin is an oral retinoid that promotes keratinocyte differentiation. Its possible side effects include dry skin, hair loss, hyperlipidemia, and hepatotoxicity. Methotrexate and acitretin are contraindicated during pregnancy. For diseases refractory to methotrexate and/or cyclosporine or when second-line therapies are not appropriate, biologic therapies or oral small molecule inhibitors may be considered.

Biologics are monoclonal antibodies or soluble receptors that target proinflammatory cytokines. They have had a dramatic impact on moderate to severe disease outcomes. Multiple biologic therapies have been approved for use in moderate-severe psoriasis, such as TNF (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and certolizumab), IL-12/23p40 (ustekinumab), IL-23p19 (rizankizumab, guselkumab and tildrakizumab), IL- 17 (ixekizumab). ) and secukinumab) and IL-17 receptor inhibitors (brodalumab). There is no single "best" agent and the choice of biologic must be adapted to the needs of each patient.

Currently, this is mainly influenced by clinical information, for example, psoriasis factors (disease phenotype and presence of PsA and previous history results). biologic treatment), comorbidities (demyelinating disease and inflammatory bowel disease), drug-specific factors (dosing frequency), and lifestyle considerations (conception plans). Genomic information has the potential to guide the effective deployment of therapies in the future, and this is an active field of research.

Although highly effective, biologics require regular subcutaneous or intravenous administration. Oral small molecule inhibitors, such as apremilast (phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor) and dimethyl fumarate, are licensed for use in moderate to severe psoriasis, and trials are underway for small molecules that block tyrosine kinase 2 in Janus kinase ( JAK), signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins. (STAT) via.

Pustular psoriasis

Pustular psoriasis is a distinct phenotype characterized by sterile pustules, which may be acutely generalized (generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP)) or limited to the fingers (Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua (ACH)) or palms and soles (palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP)). . GPP can present acutely with a generalized eruption of superficial pustules and erythematous skin.

Patients may not feel well with fever, and blood tests typically show neutrophilia and elevated inflammatory markers.27 While GPP can be life-threatening, localized pustulosis can also severely affect daily activities.

Despite the growing arsenal of treatments for plaque psoriasis, effective treatment of pustular psoriasis remains an area of great unmet need. PPP and ACH are notoriously recalcitrant to treatments used in plaque psoriasis. Potent topical steroids with occlusion are first line.

PUVA may be considered in palmoplantar pustulosis, but systemic treatments are often required.10 For severe acute GPP, cyclosporine or infliximab may be necessary for rapid onset of action. Advances in our understanding of the pathogenic role of IL36RN mutations in GPP have also led to the development of IL-36 receptor inhibitors, with trials ongoing.

Conclusion In summary, psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin condition that is predominantly determined by genetic factors and is associated with significant medical and psychosocial comorbidities. Advances in understanding its pathophysiology have led to an increasing number of therapeutic options that could dramatically improve the lives of people with psoriasis. |