Summary At least 10,000 species of viruses have the capacity to infect humans, but currently, the vast majority circulate silently in wild mammals1,2. However, climate and land use change will produce new opportunities for virus exchange between previously geographically isolated wildlife species3,4. In some cases, this will facilitate zoonotic spread, a mechanistic link between global environmental change and disease emergence. Here, we simulate potential hotspots of future viral exchange, using a phylogeographic model of the mammalian virus network and projections of geographic range changes for 3,139 mammal species under climate change and land use scenarios for the year 2070. We predict that species will aggregate in new combinations at high elevations, in biodiversity hotspots, and in areas of high human population density in Asia and Africa, driving new interspecies transmission of their viruses about 4,000-fold. Because of their unique dispersal ability, bats account for the majority of novel viral exchange and are likely to share viruses along evolutionary pathways that will facilitate future emergence in humans. Surprisingly, we find that this ecological transition may already be underway, and keeping warming below 2°C within the century will not reduce future viral exchange. Our findings highlight the urgent need to combine viral surveillance and discovery efforts with biodiversity surveys that track species distribution changes, especially in tropical regions that host the most zoonoses and are experiencing rapid warming. |

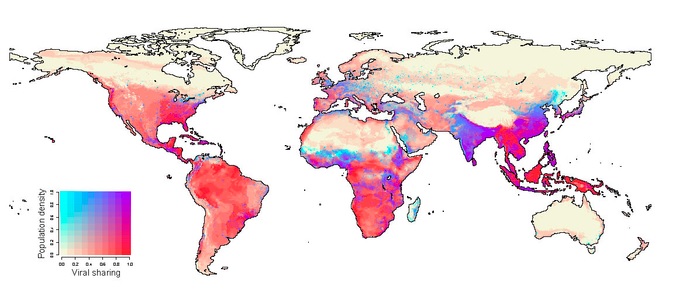

By 2070, human population centers in equatorial Africa, southern China, India, and Southeast Asia will overlap with projected hotspots of interspecies viral transmission in wildlife.

Comments

As Earth’s climate continues to warm, researchers predict that wild animals will be forced to move their habitats, likely to regions with large human populations, dramatically increasing the risk of a viral jump to humans that could lead to the next pandemic.

This link between climate change and viral transmission is described by an international research team led by scientists at Georgetown University and published in Nature .

In their study, the scientists conducted the first comprehensive assessment of how climate change will reshape the global virome of mammals. The work focuses on geographic range shifts – the journeys species will take as they follow their habitats into new areas. When they meet other mammals for the first time, the study projects that they will share thousands of viruses.

They say these changes provide greater opportunities for viruses like Ebola or coronaviruses to emerge in new areas, making them harder to track, and in new types of animals, making it easier for viruses to jump through a kind of "springboard" towards humans.

"The closest analogy is actually the risks we see in the wildlife trade," says the study’s lead author, Colin Carlson, PhD, a research assistant professor in the Center for Global Health Sciences and Security at the Center Georgetown University doctor. “We worry about markets because putting unhealthy animals together in unnatural combinations creates opportunities for this gradual emergence process, like the way SARS jumped from bats to civets, and then from civets to people. But markets are no longer special; In a changing climate, that kind of process will be the reality in nature almost everywhere.”

Worryingly, animal habitats are moving disproportionately in the same places as human settlements, creating new hotspots of indirect risk. Much of this process may already be underway in today’s 1.2 degree warmer world, and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions may not prevent these events from unfolding.

Another important finding is the impact that rising temperatures will have on bats, which account for the majority of the new viruses shared. Their ability to fly will allow them to travel long distances and share most viruses. Due to their central role in viral emergence, the greatest impacts are projected in Southeast Asia, a global hotspot of bat diversity.

“At every step,” Carlson said, “our simulations have taken us by surprise. We’ve spent years double-checking those results, with different data and different assumptions, but the models always lead us to these conclusions. "It’s a really impressive example of how well we can actually predict the future if we try."

As viruses begin to jump between host species at an unprecedented rate, the authors say the impacts on conservation and human health could be dramatic.

"This mechanism adds another layer to how climate change will threaten human and animal health," says the study’s co-senior author, Gregory Albery, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Biology at Georgetown University’s School of Arts and Sciences. .

"It is not clear exactly how these new viruses might affect the species involved, but many of them are likely to translate into new conservation risks and fuel the emergence of new outbreaks in humans."

Taken together, the study suggests that climate change will become the largest upstream risk factor for disease emergence, surpassing higher profile problems such as deforestation, wildlife trade and industrial agriculture. The authors say the solution is to pair wildlife disease surveillance with real-time studies of environmental change.

“When a Brazilian free-tailed bat reaches Appalachia, we need to invest in knowing what viruses accompany it,” Carlson says. “Trying to detect these host jumps in real time is the only way we will be able to prevent this process from causing more infections and more pandemics.”

“We are closer than ever to predicting and preventing the next pandemic,” Carlson says.

“This is a big step towards prediction; “Now we have to start working on the more difficult half of the problem.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic and the earlier spread of SARS, Ebola and Zika show how a virus that jumps from animals to humans can have massive effects. To predict its jump to humans, we need to know about its spread among other animals,” said Sam Scheiner, program director at the US National Science Foundation (NSF), which funded the research. “This research shows how animal movements and interactions due to a warmer climate could increase the number of viruses that jump between species.”