Research Highlights:

|

Summary

Background:

Lifestyle intervention and metformin have been shown to prevent diabetes; However, its effectiveness in preventing cardiovascular diseases associated with the development of diabetes is unclear. We examined whether these interventions reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events over a median follow-up of 21 years of participants in the DPP (Diabetes Prevention Program) and DPPOS (Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study) trial.

Methods:

During the DPP, 3,234 participants with glucose intolerance were randomly assigned to metformin 850 mg twice daily, intensive lifestyle, or placebo, and followed for 3 years. During the next 18 years of average follow-up in DPPOS, all participants were offered a less intensive group lifestyle intervention, and metformin was continued open-label in the metformin group.

The primary outcome was the first occurrence of nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death adjudicated according to standard criteria. An extended cardiovascular outcome included the primary outcome or hospitalization for heart failure or unstable angina, coronary or peripheral revascularization, coronary artery disease diagnosed by angiography, or silent myocardial infarction by ECG. ECGs and cardiovascular risk factors were measured annually.

Results:

Neither metformin nor the lifestyle intervention reduced the primary outcome: hazard ratio for metformin versus placebo 1.03 (95% CI, 0.78–1.37; P = 0.81) and hazard ratio for lifestyle versus placebo 1.14 (95% CI, 0.87-1.50; P = 0.34).

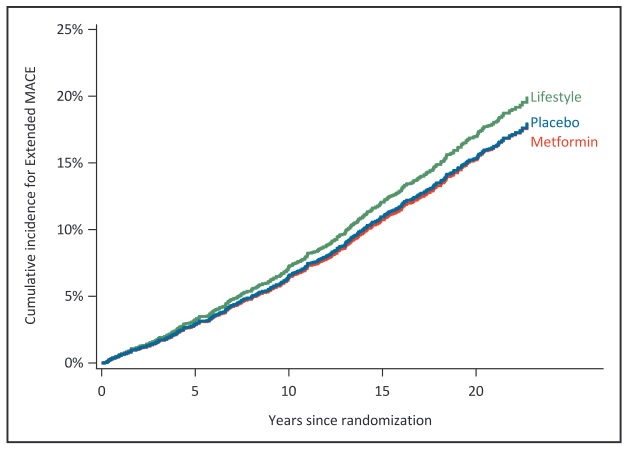

Risk factor adjustment did not modify these results. No effect of any of the interventions on extended cardiovascular outcome was observed.

Conclusion:

Neither metformin nor lifestyle reduced major cardiovascular events in DPPOS over 21 years despite long-term diabetes prevention.

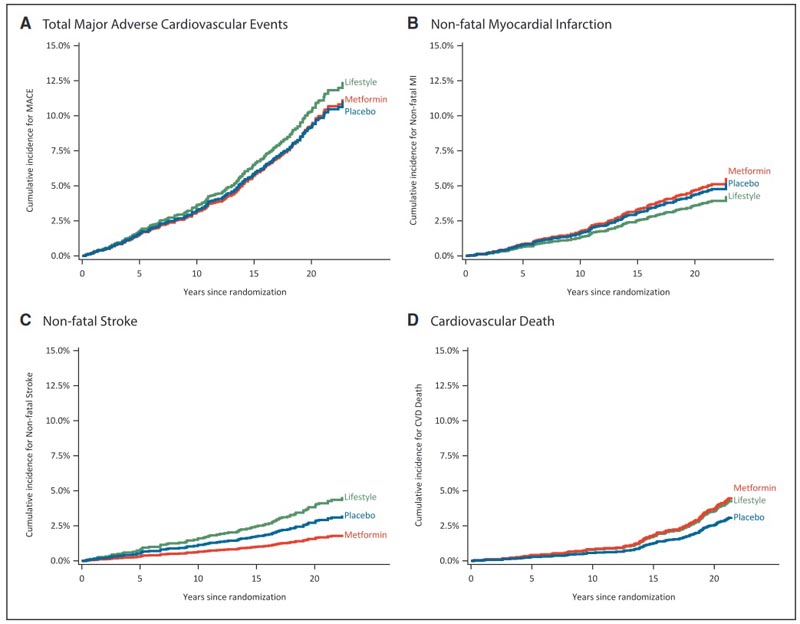

Cumulative incidence of total major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and components of individual cardiovascular events by intervention groups. A, Effects of interventions on the cumulative incidence (%) of first MACE. The first occurrence of individual MACE shown is: non-fatal myocardial infarction (B), non-fatal stroke (C), and cardiovascular death (D). The metformin group is shown in red, the lifestyle group in green, and the placebo group in blue.

Registration : URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifiers: DPP (NCT00004992) and DPPOS (NCT00038727)

Comments

Providing a group lifestyle intervention for all, extensive off-study use of statins and antihypertensive agents, and reducing use of study metformin along with off-study metformin use over time may have diluted the effects of the interventions.

A lifestyle intervention program of increased physical activity, healthy eating, and a weight loss goal of 7% or more, or taking the drug metformin were effective long-term in delaying or preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with prediabetes. However, neither approach reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease for study participants over the 21 years of the study, according to findings from the Multicenter Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS). published today in the American Heart Association’s flagship peer-reviewed journal. Circulation.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes, affecting more than 34 million people in the U.S., representing nearly 11% of the U.S. population, according to the Report 2020 National Diabetes Statistics from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death and disability among people with T2D. Type 2 diabetes occurs when the body cannot efficiently use the insulin it produces and the pancreas cannot produce sufficient amounts of insulin. Adults with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to die from cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks, strokes, or heart failure, compared to adults who do not have type 2 diabetes. People with T2D often have other risk factors of cardiovascular diseases, such as overweight or obesity, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

The DPPOS evaluated 21 years of follow-up (through 2019) for the 3,234 adults who participated in the original 3-year Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial. This DPPOS analysis focused on determining whether the drug metformin or lifestyle intervention could reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease or the rate of major cardiac events, such as heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular disease.

“The risk of cardiovascular disease in people with prediabetes increases, and the risk of CVD increases even more over time after type 2 diabetes develops and progresses,” said Ronald B. Goldberg, MD, chair of the writing group of DPPOS and professor of medicine. , biochemistry and molecular biology in the division of diabetes, endocrinology and metabolism, and senior faculty member and co-director of the Diabetes Research Institute Clinical Laboratory at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida. “We focused on evaluating the impact of lifestyle or metformin interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in people with prediabetes to reduce cardiovascular disease.”

The DPP was a landmark randomized trial from 27 centers in the US from 1996 to 2001 to evaluate how to prevent or delay the onset of T2D in people with prediabetes. Study participants were evaluated and accepted into the DPP based on these criteria: initially, a 2-hour glucose reading of 140-199 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test; fasting glucose levels of 95-125 mg/dL; and body mass index of 24 kg/m2 or higher.

A racially diverse group of 3,234 adults was studied in the original DPP for almost three years. The participants had an average age of 51 years , and almost 70% of the participants were women. People in the intensive lifestyle intervention group (nutritional improvement and physical activity aimed at achieving 7% weight loss) reduced the incidence of developing T2DM by 58%, and participants taking doses of metformin times a day had a 31% reduced incidence for T2D, compared with people in the placebo group who received standard care, which included information about effective treatment and management of T2D at the time of diagnosis.

The DPPOS began in 2002 and was open to all participants in the original DPP trial. The DPPOS enrolled nearly 90% of the original study participants for up to 25 years of follow-up to evaluate the long-term impact of the interventions on the development of T2D and its complications.

Due to the success of the lifestyle intervention, all study participants were offered to participate in the lifestyle intervention through a group format over a one-year bridging period.

The group taking metformin in the original DPP trial were able to continue taking the drug during DPPOS, and they knew they were taking metformin, not the placebo. (The metformin and placebo groups were blinded in the original DPP, so participants did not know whether they were taking metformin or placebo during that time period.)

“From the beginning of the Diabetes Prevention Program we were primarily interested in whether diabetes prevention would lead to a reduction in the development of complications caused by type 2 diabetes: cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, retinopathy and neuropathy,” he said. Goldberg. “Controlling blood glucose levels is important and we encourage interventions to prevent the long-term complications of type 2 diabetes.”

The DPPOS evaluated cardiovascular disease outcomes to determine the effects of lifestyle and metformin interventions on participants’ risk of experiencing a nonfatal heart attack, stroke, or death due to a cardiovascular event, comparing the results of each intervention group with the placebo group. The researchers reported results based on a median follow-up of 21 years , which included the three-year median follow-up period of the original DPP trial. The authors performed a futility analysis of cardiovascular outcomes, which resulted in termination of the study before completing the planned 25-year follow-up.

Throughout the entire study, participants were evaluated annually with electrocardiogram testing; measures of your risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including smoking, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure levels; and body mass index measurements. The percentage of all participants taking blood pressure- and cholesterol-lowering medications increased over the duration of the study and was slightly lower among participants in the lifestyle group compared to the other two groups.

After an average follow-up of 21 years, the researchers found no significant differences in the incidence of heart attacks, strokes, or cardiovascular death among the three intervention groups.

Specifically, the analysis found:

- There was a continued reduction or delay in the development of T2D for up to 15 years.

- The number of nonfatal heart attacks in each group was similar: 35 heart attacks occurred in the lifestyle intervention group; 46 in the metformin group; and 43 in the placebo group.

- Similarities were also found in the number of non-fatal strokes: 39 stroke incidences in the lifestyle intervention group; 16 in the metformin alone group; and 28 in the placebo group.

- The number of deaths from cardiovascular events was low: 37 deaths among lifestyle intervention participants; 39 in the metformin group; and 27 in participants who took the placebo during the original DPP trial.

“The fact that neither a lifestyle intervention program nor metformin led to a decrease in cardiovascular disease among people with prediabetes may mean that these interventions have limited or no effectiveness in preventing cardiovascular disease, although they are very effective in preventing or delaying its development. Type 2 diabetes,” Goldberg said. “It is important to note that most study participants were also treated with cholesterol and blood pressure medications , which are known to reduce the risk of CVD. Therefore, the low rate of cardiovascular disease development found overall may be due to these medications, making it difficult to identify a beneficial effect of lifestyle or metformin intervention. "Future research is needed to identify higher-risk subgroups to develop a more targeted approach to cardiovascular disease prevention in people with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes."

There were several limitations to the study. The researchers selected a subgroup of people who met the criteria for prediabetes; however, these results cannot be generalized to all people with prediabetes. Furthermore, the intensity of the lifestyle intervention was reduced after the initial DPP phase and, over the 21-year study period, there was a gradual reduction in medication adherence by participants in the DPP group. metformin.

There was also metformin use outside of the study in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, which may have diluted differences between the study groups. The high level of blood pressure and cholesterol medications prescribed by the participants’ primary care team, as well as the lower use of blood pressure medications in the lifestyle group, may have influenced the results. There may also be an underestimation of cardiovascular events, as some participants did not complete the 21 years of follow-up.

"These long-term findings confirm that the link between type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease is complex and requires more research to better understand," said American Heart Association medical director for prevention Eduardo Sanchez, MD, MPH, FAHA, FAAFP, and clinical lead for Know Diabetes by Heart, a collaborative initiative between the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association that addresses the link between diabetes and cardiovascular disease. “However, these important results also tell us that lifestyle intervention is incredibly effective in delaying or preventing type 2 diabetes, which, in itself, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease. “The CDC estimates that nearly 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. has prediabetes, so preventing or delaying type 2 diabetes is a public health imperative to help prolong and improve the lives of millions of people.”

Effect of metformin and lifestyle interventions versus placebo on the cumulative incidence of extended major adverse cardiovascular event (extended MACE) outcome. The figure shows the effects of the interventions on the cumulative incidence (%) of the first occurrence of the extended cardiovascular event outcome. The metformin group is shown in red, the lifestyle group in green, and the placebo group in blue.

Clinical perspective What’s new? •During the 21 years of follow-up of the 3,234 DPP (Diabetes Prevention Program) participants who started with glucose intolerance and were followed in the DPPOS (Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study), neither metformin nor lifestyle interventions reduced major adverse cardiovascular events compared with placebo, despite decreasing the development of diabetes. the provision of a less intensive lifestyle intervention for all DPPOS participants and increased use of metformin outside the study over time, which may have limited the apparent effects of the interventions and have been valuable preventive strategies. What are the clinical implications? • Despite a significant long-term reduction in the development of diabetes, metformin and lifestyle interventions may not have additional effects in preventing cardiovascular disease in the context of glucose intolerance or type 2 diabetes early with minimal cardiovascular disease and modern treatment strategies for glucose lowering, lipid lowering, and antihypertensives. • Metformin and lifestyle intervention reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, but may not provide additional protection against cardiovascular disease when blood glucose, lipids, and blood pressure are well controlled. |

Co-authors are Trevor J. Orchard, MD; Jill P. Crandall, MD; Edward J. Boyko, MD, MPH; Matthew Budoff, MD; Dana Dabelea, M.D., Ph.D.; Kishore M. Gadde, MD; William C. Knowler, MD, Dr.PH; Christine G. Lee, MD, MS; David M. Nathan, MD; Karol Watson, MD; and Marinella Temprosa, Ph.D. Author disclosures are listed in the manuscript.