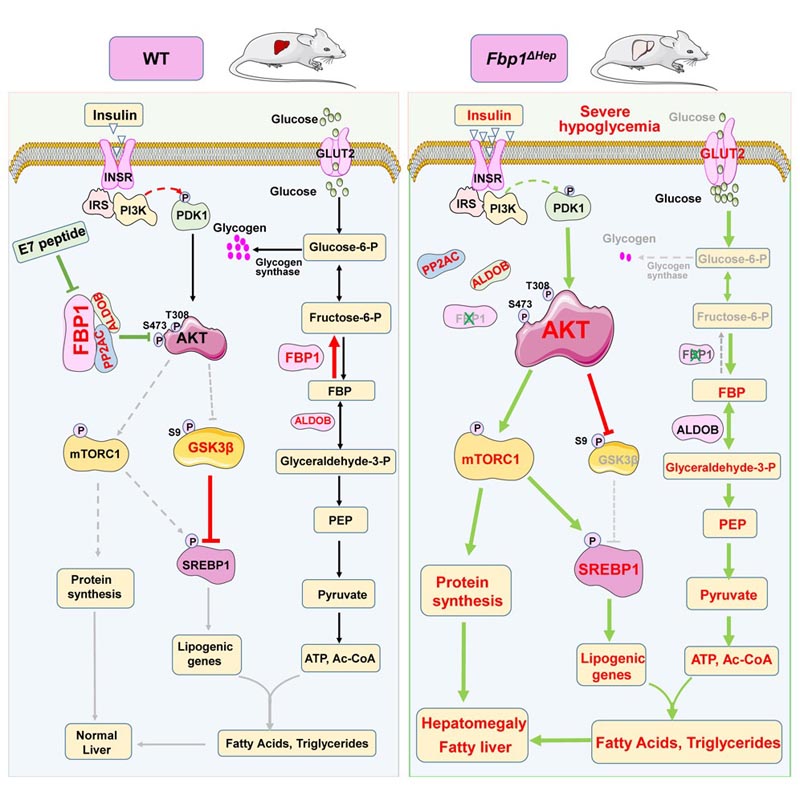

Summary Insulin inhibits gluconeogenesis and stimulates the conversion of glucose to glycogen and lipids. It is unclear how these activities are coordinated to prevent hypoglycemia and hepatosteatosis. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1) controls the rate of gluconeogenesis. However, congenital deficiency of human FBP1 does not cause hypoglycemia unless accompanied by fasting or starvation, which also trigger paradoxical hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis, and hyperlipidemia. Mice with FBP1 hepatocyte ablation exhibit identical pathologies conditioned by fasting along with hyperactivation of AKT, whose inhibition reversed hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis and hyperlipidemia, but not hypoglycemia. Surprisingly, fasting -mediated AKT hyperactivation is insulin dependent. Independently of its catalytic activity, FBP1 prevents insulin hyperresponsiveness by forming a stable complex with AKT, PP2A-C, and aldolase B (ALDOB), which specifically accelerates the dephosphorylation of AKT. Enhanced by fasting and weakened by elevated insulin, the formation of the FBP1:PP2A-C:ALDOB:AKT complex, which is disrupted by human FBP1 deficiency mutations or a C-terminal FBP1 truncation, prevents liver pathologies caused by insulin and maintains lipid and glucose homeostasis. In contrast, a complex disrupting peptide derived from FBP1 reverses diet-induced insulin resistance. |

Comments

Just over a century has passed since the discovery of insulin, a period of time during which the hormone’s therapeutic powers have been expanded and refined. Insulin is an essential treatment for type 1 diabetes and often type 2 diabetes as well. About 8.4 million Americans use insulin, according to the American Diabetes Association.

One hundred years of research has greatly advanced the medical and biochemical understanding of how insulin works and what happens when it is missing, but the converse—how potentially fatal insulin hyperreactivity is prevented—remains a persistent mystery.

In a new study, published in Cell Metabolism , a team of scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, along with colleagues elsewhere, describe a key player in the defense mechanism that protects us against excess of insulin in the body.

"Although insulin is one of the most essential hormones, insufficiency of which can lead to death, too much insulin can also be fatal," said the study’s senior author, Michael Karin, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology and Pathology at the School of Medicine. from UC San Diego.

"While our body fine-tunes insulin production, patients who are treated with insulin or medications that stimulate insulin secretion often experience hypoglycemia , a condition that if unrecognized and untreated can lead to seizures, coma, and even death. death, which collectively define a condition called insulin shock."

Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) is a leading cause of death among people with diabetes .

In the new study, Karin, first author Li Gu, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Karin’s lab, and colleagues describe "the body’s natural defense or safety valve " that reduces the risk of insulin shock.

That valve is a metabolic enzyme called fructose-1,6-bisphosphate phosphatase or FBP1 , which acts to control gluconeogenesis , a process in which the liver synthesizes glucose (the main source of energy used by cells and tissues) during sleep and secretes it to maintain a constant supply of glucose in the bloodstream.

Some antidiabetic drugs, such as metformin, inhibit gluconeogenesis but without apparent harmful effects. Children who are born with a rare genetic disorder in which they do not produce enough FBP1 can also remain healthy and live long lives.

But in other cases, when the body lacks glucose or carbohydrates, an FBP1 deficiency can lead to severe hypoglycemia . Without a glucose infusion, seizures, coma, and possibly death can occur.

To compound and confuse the problem, FPB1 deficiency combined with glucose starvation produces adverse effects unrelated to gluconeogenesis, such as an enlarged fatty liver , mild liver damage, and elevated levels of lipids or fats in the blood.

To better understand the functions of FBP1, the researchers created a mouse model with liver-specific FBP1 deficiency, precisely mimicking the human condition. Like FBP1-deficient children, the mice appeared normal and healthy until fasting, which quickly resulted in severe hypoglycemia and liver abnormalities and hyperlipidemia described above.

Gu and his colleagues discovered that FBP1 had multiple functions. Beyond playing a role in the conversion of fructose to glucose, FBP1 had a second non-enzymatic but critical function: it inhibited the protein kinase AKT, which is the main pathway for insulin activity.

"Basically, FBP1 keeps AKT in check and protects against insulin hyperreactivity, hypoglycemic shock, and acute fatty liver disease," said first author Gu.

Working with Yahui Zhu, a visiting scientist at Chongqing University in China and second author of the study, Gu developed a peptide (a chain of amino acids) derived from FBP1 that disrupted the association of FBP1 with AKT and another protein that inactivates AKT.

"This peptide works as an insulin mimetic , activating AKT," Karin said. "When injected into mice that have become insulin resistant, a very common prediabetic condition, due to prolonged consumption of a high-fat diet, the peptide (nicknamed E7) can reverse insulin resistance and restore glycemic control. normal".

Karin said researchers would like to continue developing E7 as a clinically useful alternative to insulin "because we have every reason to believe that it is unlikely to cause insulin shock."