Summary The current definition of prediabetes is controversial and subject to continuous debate. However, prediabetes is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes, has a high prevalence and is associated with diabetic complications and mortality. Therefore, it has the potential to become a major strain on healthcare systems in the future, requiring action from policymakers and healthcare providers. But how can we best reduce its associated burden on health? As a compromise between different opinions in the literature and among the authors of this article, we suggest stratifying people with prediabetes according to estimated risk and only offering preventive interventions at the individual level to people at high risk . At the same time, we advocate identifying people with established prediabetes and diabetes-related complications and treating them as we would treat people with established type 2 diabetes. |

More than 20 years ago, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) replaced the terms “impaired glucose tolerance” (IGT) and “impaired fasting glucose” (IBG) with “prediabetes” in its standards of care, a controversial move. which has since sparked heated debates.

Proponents of the change argue that the term is useful for potential prevention at the individual level, while opponents argue that labeling all individuals with intermediate hyperglycemia as having a pre-existing disease medicalizes a large portion of the population.

Disagreement also includes the definition of prediabetes/intermediate hyperglycemia , and how to approach individuals identified with prediabetes. Despite the controversy, the term prediabetes has found use with (some) healthcare providers and government organizations.

Why should people with prediabetes be identified?

The prevalence of prediabetes is high and, on average, people with prediabetes are at higher risk of developing diabetes, diabetic complications and other related diseases, compared to those with normal blood glucose levels. Consequently, the burden of prediabetes on the health of the population is substantial, which underlines the need to initiate preventive actions early to avoid the development of diseases.

However, at the same time, there is great heterogeneity in the individual risk of people with prediabetes. And here lies the puzzle: How to ensure early intervention in those with progressive problems, while trying to find the balance between undertreatment and overtreatment ? This balance is essential to avoid unnecessary medicalization and stigma, to guarantee the necessary number to be treated, in time and with the resources required by prevention programs, and also to keep health costs under control.

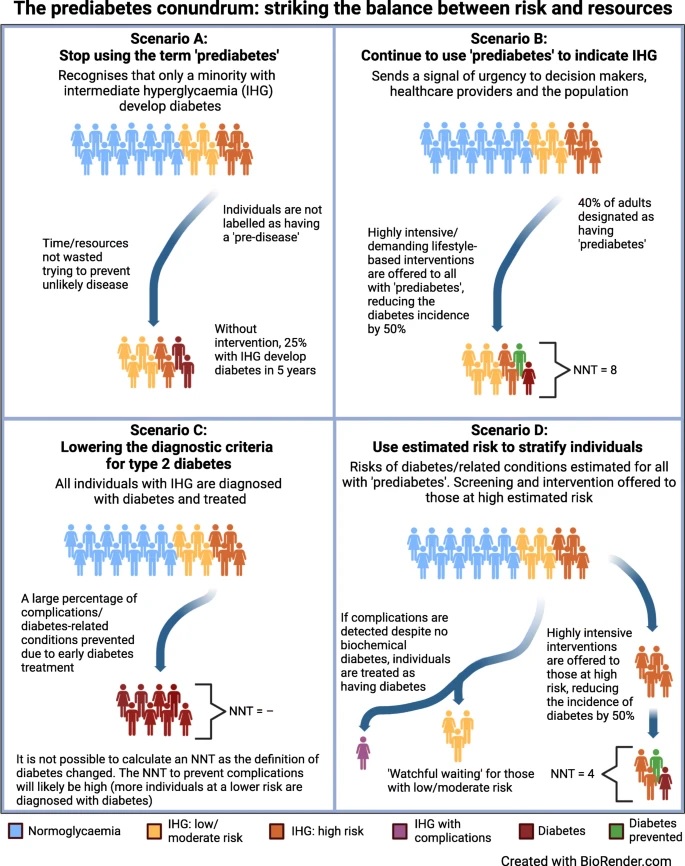

Opinions on how to address prediabetes vary greatly. Some support the current definition, while others propose rethinking the approach to identifying people at risk, including more risk markers . There are others who want to completely abandon the concept of prediabetes; it has even been suggested to reduce the diagnostic threshold for diabetes to include the prediabetic range. All of these alternatives can have both positive and negative consequences.

| Definition and history of prediabetes and intermediate hyperglycemia |

Type 2 diabetes is a multifactorial and multisystem metabolic disease.

However, for historical and practical reasons, the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes is based solely on blood glucose or HbA1c levels. Prediabetes is defined as the presence of intermediate hyperglycemia in the form of at least one of the following: “impaired glucose tolerance” ( IGT), “impaired fasting glucose” (IFG) or slightly elevated HbA1c .

However, the overlap between individuals identified with prediabetes using the different criteria is relatively poor. Furthermore, although the literature does not show a clear threshold for subsequent diabetes risk, specific but variable cut-off points are used to define prediabetes/intermediate hyperglycemia .

Impaired glucose tolerance ( IGT) was introduced in 1979/1980 to cover the glucose range between diabetes and normal glucose tolerance. The same glucose dose is used for all individuals while women generally have higher 2-h plasma glucose levels than men, due in part to differences in body size and volume of distribution.

“Impaired fasting glucose” ( IFG) was introduced in 1991 and was defined such that the prevalence of TGA and FIG was similar in the Paris Prospective Study cohort study . The lower cut-off point for GAA in the study was 6.1 mmol/l (NT: 110.90 mg/dl). The value is still used by the WHO. In 2003, the ADA reduced this cut-off point to 5.6 mmol/l (NT: 101.83 mg/dl), which dramatically increased the prevalence of OAG. The lower level of fasting plasma glucose was not adopted by the WHO due to lack of evidence of benefit in terms of reduction of adverse outcomes.

In 2008, an expert committee with members from the ADA, EASD, and IDF (International Diabetes Federation) concluded that HbA1c was a reliable measure of chronic hyperglycemia, associated with long-term complications. Therefore, it was suggested that HbA1c can be used for the diagnosis of diabetes. The expert committee also stated that those with HbA1c levels of 42 mmol/l (6%) to 47 mmol/mol (6.4%) should receive preventive interventions due to the relatively high likelihood of progression to diabetes. They also raised concerns regarding the use of the term “prediabetes” to label this group of people, as not all people with HbA1c in this range will develop diabetes. In 2010, the ADA expanded that the high-risk HbA1c ranges between 5.7 and 6.4%. EASD and IDF did not adopt these changes.

When using HbA1c (a proxy for blood glucose levels) as the primary diagnostic tool for (pre)diabetes, it is important to note that factors beyond plasma glucose contribute to HbA1c variation, especially in the non-diabetic range. Furthermore, there is evidence of an increasing discrepancy between HbA1c and other measures of plasma glucose with increasing age, but this needs further investigation.

Why identify people with prediabetes?

The prevalence of prediabetes is high and, on average, people with prediabetes have a higher risk of developing diabetes, diabetic complications and other related diseases, compared to those with normal blood glucose. Consequently, the health burden of prediabetes at the population level is substantial, underscoring the need for early initiatives to prevent disease development. However, at the same time, there is great heterogeneity in individual risk among those with prediabetes.

The enigma would be: How to ensure early intervention in those with progressive problems?

At the same time it is about maintaining the balance between undertreatment and overtreatment. This balance is essential to avoid unnecessary medicalization and stigma, to guarantee the necessary number to be treated in a timely manner and with resources that require prevention programs, and also to keep healthcare costs under control.

Opinions on how to address prediabetes vary greatly. Some support the current definition, while others propose rethinking the approach to identifying people at risk by including more risk markers, while others want to abandon the concept of prediabetes entirely. It has even been suggested to lower the diagnostic threshold for diabetes to include the prediabetic range. All of these alternatives can have both positive and negative consequences (electronic supplementary material).

| Prevalence of prediabetes and risk of future diseases |

At the individual level, blood glucose levels and progression to type 2 diabetes are the result of a complex interaction between genetic makeup and the social and physical environment. Therefore, the prevalence of prediabetes depends on the characteristics of the population as well as the diagnostic criteria used. Consequently, whether an individual is labeled with the diagnosis of prediabetes is based in part on the cutoff points used in their country of residence and it is often not possible to compare prevalence estimates between countries/studies.

However, regardless of the diagnostic criteria used, a significant proportion of the world’s adult population has prediabetes defined as intermediate hyperglycemia. For example, the estimated prevalence of prediabetes in adults has been reported to be ~50% in a large Chinese study and ~38% in another US study (both estimates are based on the ADA criteria for GAA , proportion and prediabetes based on HbA1c) and 17% in a Dutch cohort of adults aged 45 to 75 years (using WHO criteria for GAA and TGA).

Depending on the definition used and the population examined, 10-50% of people with prediabetes will progress to overt diabetes within the next 5 to 10 years, with greater risk in the group of individuals with “impaired glucose tolerance.” (TGA), “impaired fasting glucose” (GAA) combined. However, even more people with prediabetes (about 30–60%) will return to normal blood glucose levels in 1 to 5 years .

The high prevalence and relatively low rate of conversion to type 2 diabetes at 5 to 10 years may be due, in part, to the cutoff points used to define prediabetes (particularly with the elevated ADA and American criteria) . Association of Clinical Endocrinologists ) that remain within the reference limits for glucose levels reported in low-risk populations, especially with increasing age.

Low cut-off points could also explain why 30% of young adults with a mean body mass index (BMI) of around 25 kg/m2 , but without other apparent risk factors for diabetes, have prediabetic levels. of ADA-defined HbA1c and/or GAA in a population study from Liechtenstein.

Little is known about the lifetime risk of type 2 diabetes in people with prediabetes. In a Dutch study, the mean lifetime risk of developing type 2 diabetes at the population level depended largely on body size . For those with OAG (based on WHO criteria) and overweight/obesity (BMI >25 kg/m 2 ), the risk was >75% at age 45 years, while in individuals with OAG and BMI < 25 kg/m 2 was ~36%. Taking into account waist circumference the risk was further stratified.

Prediabetes has been associated with a long list of current and future diseases, including cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, cancer and dementia, as well as overall mortality. The risk may be higher in those with TGA, although firm evidence is lacking.

As with diabetes, the development of these outcomes comes from complex processes, and individuals with prediabetes represent a heterogeneous group with variable risk of developing complications. Results from Mendelian randomization studies of variants affecting glycemia indicate a causal relationship with coronary artery disease, even within the prediabetic range. However, the associations reported in the literature are not strong enough to use prediabetes as a screening test for the risk of subsequent complications.

| Interventions in people with prediabetes |

Type 2 diabetes can be prevented (or at least delayed) by intensive lifestyle changes in people with prediabetes, with the caveat that most trials have included people with “impaired glucose tolerance” ( TGA) often combined with overweight . Interventions targeting both individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes and entire populations have been reported to be cost-effective with respect to diabetes prevention, although some have questioned whether individual-level prevention trials can be translated to hospital settings. real world.

Programs targeting prediabetes as a high-risk condition for diabetes offer individual-level interventions, for example, the ADA. Should the diagnostic criteria for diabetes be expanded to include the prediabetic range, with a resulting large increase in the number of people with diabetes, many of whom will be at low risk of developing complications. Or should the approach to prediabetes be refined by calculating the risk of developing diabetes, complications and related conditions, and only offer individual-level interventions for those at highest risk?

Scenarios will vary, but the extent to which they do needs to be investigated, which will include an assessment of how those impacts differ between low- and high-income countries and across different welfare/health systems. In fact, prediabetes is a controversial topic, and even among the authors of this article, there are divergent opinions. “Some,” they say, “prefer to lower the diabetes diagnostic threshold to include the prediabetic range (WHO cutoff points) while others prefer to reserve the term prediabetes for patients at estimated high risk. However, regardless of our personal views, we cannot afford to ignore the substantial burden of disease caused by prediabetes/intermediate hyperglycemia , both now and, even more so, in the future.”

Given the limited resources available and the seriousness of the issue, the authors suggest that the best compromise is to retain the term prediabetes in its current form, but adopted a stratified , precision medicine approach to detection and prevention based on estimated risk. . This recognizes the variable risk among individuals with prediabetes and allows the identification of those who will develop complications, despite not having diabetes according to the biochemical definition.

The stratified approach will help ensure a reasonable number needed to treat with preventive interventions, while controlling costs. Moving toward stratification of those with prediabetes (and those without) for short-term and estimated lifetime risk of diabetes, diabetes-related complications, and other comorbidities is suggested. The estimated risk can serve as a basis for more informed conversations at the individual level about the prevention of diabetes and related diseases, and therefore support shared decision-making.

It is expected that most people at low to moderate risk will enter a form of “watchful waiting” for life, with regular reassessment of their risk. as well as other risk factors for more difficult endpoints, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia, people at high risk of diabetes and related complications, who will need lifelong support, including body weight control.

Intervening upon the development of overt diabetes will likely make returning to “normal” glucose metabolism easier compared to achieving diabetes remission. As part of this approach, the authors suggest screening people at high estimated risk for prevalent diabetes-related complications. If complications are found , these people should be treated as if they had overt diabetes despite having glycemic levels below the threshold for diagnosing diabetes. Leaning towards biochemical diagnostic criteria in these cases is the same as ignoring that other factors, beyond glycemic levels, play a role in the development of diabetic complications.

Studying the feasibility of a screening and treatment approach for diabetic complications in individuals at high risk for diabetes without a biochemical basis will be an important avenue for future research. The authors argue that it relies heavily on risk drivers that can reliably identify the absolute risk of a range of outcomes, both future and established. This is partially possible using existing risk engines, such as the QDiabetes (NT: diabetes risk calculator), but, according to the authors, more advanced models are needed to implement their suggestion. These risk engines must be able to robustly predict the risk of a range of relevant outcomes.

The next step will be to establish the cut-off points for estimating the risk at which to offer interventions at the individual level. This will requires research on the cost-benefit relationship, both for individuals with prediabetes (efforts vs. potential gains in personal health) and societies. Furthermore, the authors encourage the research community and decision makers to increase attention and resources towards this area. This should include a focus on how to improve the delivery and communication of risk estimates to people at risk. If implemented, the risk assessment refinement will address some of the challenges arising from using the lower cut points for prediabetes suggested by the ADA, including the low/moderate positive predictive value of developing diabetes.

The metabolic aberrations that lead to diabetes, diabetic complications, and other related diseases are (probably) chronic and require long-term, if not lifelong, interventions.

Evidence of the long-term effectiveness of prevention programs is currently lacking. Such trials require resources and a lot of follow-up time. Stratifying treatment intensity by estimated risk should theoretically reduce the number needed to treat and increase the likelihood that such interventions can reduce the incidence of adverse outcomes. However, this does not solve the problem of adherence to long-term treatment.

If the focus is to effectively reduce the health burden caused by prediabetes, an important avenue of research would be to identify which interventions are effective and tolerable over longer periods of time in subgroups of people with prediabetes. Importantly, the individual approach cannot be the only one , the authors emphasize, adding: “we strongly encourage policymakers to prioritize population approaches.”

Population -level interventions have the potential to change the risk distribution of a population and improve the average metabolic profile, which will benefit the population as a whole. Such interventions are outside the scope of the healthcare system and must rely on cross-sector collaborations with strong leadership from policymakers who must implement structural changes in society to promote healthier lives.

“We,” say the authors, “the doctors and the scientific community are important advocates in this regard, as they can guide policymakers in this direction. In the meantime, we would like to remind everyone that even staunch advocates of using the term prediabetes, such as the ADA, emphasize that prediabetes is not a disease but a risk factor . Therefore, we encourage everyone to be cautious and not label prediabetes as an actual pre-existing disease, when addressing individuals, the public and decision makers.”

In conclusion , the authors advocate for a more refined approach to risk and prevention in people with prediabetes to balance the resources expended by both individuals and societies.