Clinical vignette A 53-year-old woman with a significant medical history of hypertension presents to the emergency department with headache and dizziness . Her symptoms have been constant for the last two weeks. Her primary care physician diagnosed her with peripheral vertigo and sent her home on meclizine, which has not provided symptom relief. Physical exam Triage vital signs (VS) include BP 163/89, HR 78, T 98.4, RR 14, SpO2 98% on room air. No nystagmus was observed on examination. His extraocular movements and cranial nerves II-XII are intact, all four extremity strength is 5/5 without any focal weakness, and there are no noticeable sensory deficits. There is, however, dysmetria of the right upper extremity. |

Images

Non-contrast head CT reveals the following:

Which is the diagnosis?

Answer : Cerebellar stroke

Epidemiology:

1-4% of strokes occur in the cerebellum.

In the United States, approximately 795,000 people suffer strokes each year.

Cerebellar strokes are associated with high morbidity and mortality . Edema associated with infarction can cause herniation, increased brainstem pressure, or obstruction of the fourth ventricle leading to obstructive hydrocephalus.

Compared to cerebral strokes, the mortality rate associated with cerebellar strokes is almost doubled .

While strokes in pediatric patients are rarer, posterior circulation strokes account for 30-40% of all childhood strokes.

The literature suggests that the average age of patients is 62 years , with the most common underlying causes being atherosclerotic or cardioembolic disease. Less commonly, vertebral artery dissections will lead to cerebellar strokes which can be seen in younger patients .

Pathophysiology:

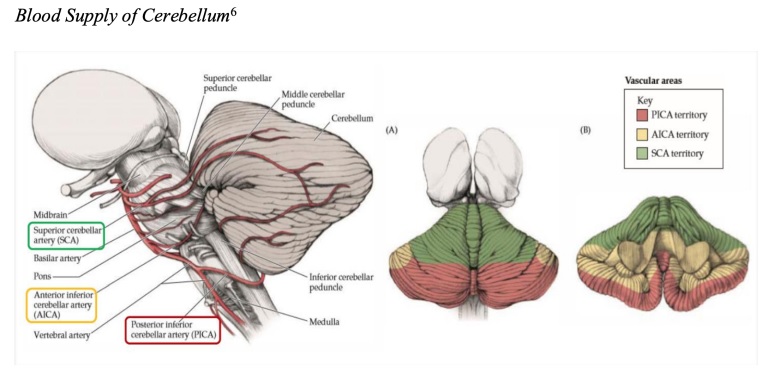

The cerebellum is supplied by three main arteries: the superior cerebellar artery, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Different types of cerebellar strokes can be defined by their vascular supply, although physical manifestations can often overlap or be atypical.

Superior cerebellar artery strokes most often present with headache, gait ataxia, dysarthria . Dizziness and vomiting are observed less frequently.

Posterior inferior cerebellar artery strokes present with severe dysphagia, dysarthria, dysphonia , also known as lateral medullary syndrome .

Anterior inferior cerebellar artery strokes, also known as lateral pontine syndrome , present with the most widespread symptoms. This includes severe vertigo, nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, ipsilateral hemiataxia, ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, facial weakness, loss of lacrimation, loss of salivation, loss of taste in the anterior 2/3 of the tongue, loss of corneal reflex, loss of pain and temperature of the ipsilateral face and contralateral body.

Assessment:

Distinguishing the difference between peripheral and central vertigo can be difficult. The most important distinction is that peripheral vertigo is often accompanied by vestibulocochlear symptoms, can be triggered by positions, is intermittent, usually without headache, and does not demonstrate other neurological deficits (vision, speech, gait disturbances).

The physical examination should consist of a complete neurological examination that includes evaluation of cranial nerves, motor function, sensation, speech, nystagmus, toe-to-nose, heel-to-shin, and gait evaluation.

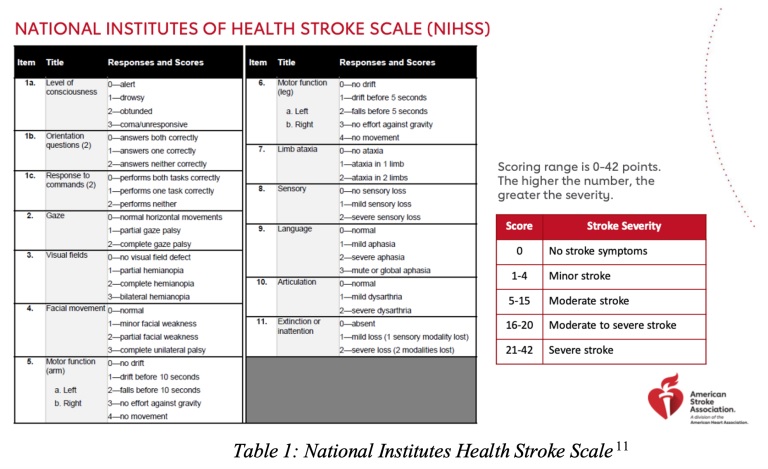

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale may also be beneficial in determining the severity of strokes, although it is most useful for strokes that affect the anterior circulation.

Initial testing should include a non-contrast CT scan of the head to evaluate for hemorrhagic stroke with the addition of a CT scan of the head and neck if there is any concern for a posterior circulation stroke.

The definitive diagnosis of cerebellar stroke is made with MRI of the brain , as CT images (both non-contrast and intravenous contrast) are often unremarkable and have low sensitivity for cerebellar stroke.

ECG and laboratory tests (glucose, CBC, electrolytes, kidney/liver function, troponin, PT/PTT) are also recommended.

Treatment:

Treatment of cerebellar strokes depends on whether the etiology of the stroke is ischemic or hemorrhagic .

Patients with intracranial hemorrhage should undergo formal neurosurgical evaluation to determine surgical or supportive treatment.

Reversal of anticoagulation as needed:

Provide prophylactic antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam 20 mg/kg IV.

Blood pressure control is key to treatment and can be controlled with boluses of labetalol and/or an infusion of nicardipine or clevidipine.

Before acute reperfusion in ischemic stroke, the target blood pressure is <185/110 .

24 hours after acute reperfusion in ischemic stroke, blood pressure goal <180/105 .

The goal of hemorrhagic stroke depends on the initial blood pressure.

Baseline systolic blood pressure 150-220, target systolic blood pressure 140.

Baseline systolic blood pressure > 220, target systolic blood pressure 140-160.

Administer a 100 mL bolus of 3% hypertonic saline or mannitol for signs and symptoms of cerebral edema.

Keep the head of the bed elevated to 30 degrees and if the patient is intubated, adjust the respiratory rate higher to temporarily treat cerebral edema until definitive management.

Cerebellar infarcts may be candidates for thrombolysis if they are within the correct time of 4.5 hours and the deficit is significant enough to justify its use, since there is a high risk of bleeding.

If there is no thrombolysis, they should receive aspirin 324 mg.

If receiving thrombolysis, aspirin should be continued for 24 hours.

Endovascular therapy, including mechanical thrombectomy and aspiration, is reserved for severe posterior circulation strokes, as the benefit has historically not been better than medical treatment.

Driving:

Patients with diagnosed cerebellar stroke or with high suspicion of cerebellar stroke should be admitted for further evaluation and management.

Admit to a telemetry floor or neurological intensive care unit depending on clinical presentation and management. Patients receiving thrombolysis will require admission to the ICU for neurological monitoring.

Pearls to remember:

|