The thymus is critical for the normal development of the immune system. Infants who undergo thymectomy have reduced T cell counts that do not recover to normal levels even after several years of follow-up and have altered immune responses to childhood vaccines. Children with congenital heart defects who undergo thymectomy during surgery have a reduction in naïve T cell counts that persists into adulthood.

It is less clear whether the thymus is essential for adult health, especially because the thymus regresses naturally with age. Thymus atrophy begins in childhood and markedly accelerates at puberty, resulting in an exponential decrease in the generation of new T cells. With the decline in central T cell production, the body maintains the number of T cells through peripheral clonal proliferation of T cell populations that have an increasingly limited repertoire of T cell receptors (TCRs) as a result of stimulation of only a fraction of the TCRs.

Age-related contraction of the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire may hamper immune surveillance , increasing the risk of infection and cancer and may be a risk factor in the development of autoimmune diseases.

Previous studies have shown that although the thymus continues to produce T cells into adulthood, thymic activity gradually declines with age.

How important, then, is the adult thymus?

We addressed this question by evaluating health outcomes among adults who had undergone thymectomy.

Thymectomy is performed using a median sternotomy, video- or robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, or transcervical dissection. Therefore, patients who had undergone cardiothoracic surgery without thymectomy were chosen to control the effect of the surgical procedure. Through epidemiological, clinical and immunological analyses, we investigated the influence of thymectomy on mortality and the risk of infection, cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Background

The function of the thymus in human adults is unclear and routine removal of the thymus is performed in a variety of surgical procedures. We hypothesize that the adult thymus is necessary to maintain immunological competence and general health.

Methods

We assessed the risk of death, cancer, and autoimmune disease among adult patients who had undergone thymectomy compared with demographically matched controls who had undergone similar cardiothoracic surgery without thymectomy . T cell production and plasma cytokine levels were also compared in a subgroup of patients.

Results

After exclusions, 1420 patients who had undergone thymectomy and 6021 controls were included in the study; 1146 of the patients who had undergone thymectomy had a matched control and were included in the primary cohort.

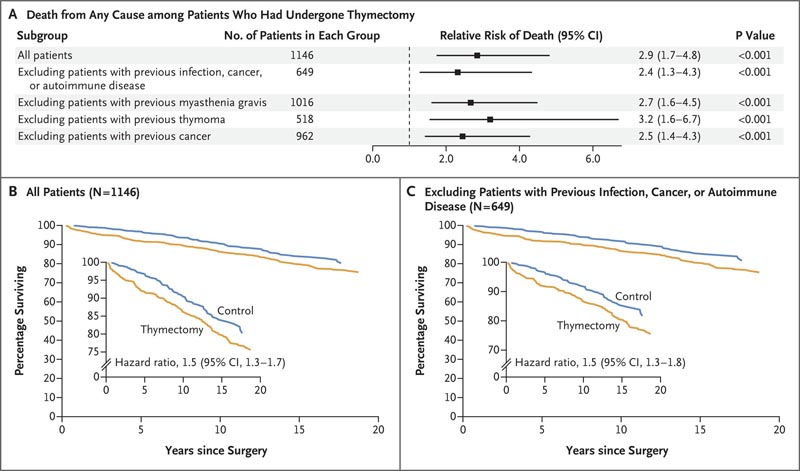

At 5 years after surgery, all-cause mortality was higher in the thymectomy group than in the control group (8.1% vs. 2.8%; relative risk, 2.9; confidence interval [ 95% CI, 1.7 to 4.8), as was the risk of cancer (7.4% vs. 3.7%; relative risk, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3 to 3.2).

Although the risk of autoimmune disease did not differ substantially between groups in the overall primary cohort (relative risk, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.4), a difference was found when patients with infection were excluded analysis, cancer, or autoimmune disease (12.3% vs. 7.9%; relative risk, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.02 to 2.2).

In an analysis involving all patients with more than 5 years of follow-up (with or without a matched control), all-cause mortality was higher in the thymectomy group than in the general US population (9 .0% vs. 5.2%), as was mortality from cancer (2.3% vs. 1.5%).

In the subgroup of patients in whom T cell production and plasma cytokine levels were measured (22 in the thymectomy group and 19 in the control group; mean follow-up, 14.2 years postoperatively), those had thymectomy had less new production of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes than controls (mean CD4+ signal joint T cell receptor cleavage circle [sjTREC] count, 1451 vs. 526 per microgram of DNA [P=0.009 ]; mean CD8+ sjTREC count, 1466 vs. 447 per microgram of DNA [ P < 0.001]) and higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the blood.

Figure: Effect of thymectomy on long-term mortality . Panel A shows the relative risk of death from any cause among patients who had undergone thymectomy compared with age-, race-, and sex-matched controls in the first 5 years after surgery, both in the overall study population and in subgroups. The relative risk of death from any cause within 5 years was increased in patients who had undergone thymectomy, regardless of whether they had a preoperative history of infection, cancer, or autoimmune disease. Panels B and C show the percentages of patients who survived over a 20-year period after surgery in the group without exclusions (Panel B) and in the subgroup in which patients with a preoperative history of infection, cancer or autoimmune disease analysis. The boxes show the same data on an expanded y-axis .

Conclusions In this study, all-cause mortality and cancer risk were higher among patients who had undergone thymectomy than among controls. Thymectomy also appeared to be associated with an increased risk of autoimmune disease when patients with preoperative infection, cancer, or autoimmune disease were excluded from the analysis. |

Discussion

In this study, we found that thymectomy in adulthood was associated with an increased risk of death from any cause and an increased risk of cancer.

These observations held even in separate analyzes in which patients with a preoperative history of potentially confounding conditions such as cancer, autoimmune disease, infection, myasthenia gravis, or thymoma were excluded. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients without a history of confounding conditions, an association between thymectomy and postoperative autoimmune disease was observed. Patients in all age groups who had undergone thymectomy were more likely to die from any cause and from cancer than controls and the general US population.

Among patients with postoperative cancer, thymectomy was associated with more aggressive recurrent disease. Furthermore, thymectomy was associated with reduced production of newly formed T cells, as reflected by persistently low sjTREC counts that extended to a median follow-up of 14.2 years postoperatively (range, 8 to 26). This finding is consistent with that of another study in which reduced sjTREC counts were found during shorter follow-up (500 days) of patients who had undergone thymectomy in adulthood for myasthenia gravis.

Finally, patients who had undergone thymectomy and had postoperative cancer were found to have more oligoclonal and less diverse TCR repertoires, which could possibly contribute to the development of cancer and autoimmune diseases. 31-33

Together, these findings support a role for the thymus in contributing to the production of new T cells in adulthood and the maintenance of adult human health. The disruption of homeostasis caused by thymectomy is sufficient to negatively impact critical health outcomes, strongly arguing that the adult thymus remains functionally important .

This study is retrospective and observational and therefore the data cannot be used to identify causality . However, they provide evidence of an association between thymectomy and adverse patient outcomes. These results strongly suggest that, when possible, preservation of the thymus should be a clinical priority.

(Funded by Tracey and Craig A. Huff Harvard Stem Cell Institute Research Support Fund and others.)