Summary Some commonly prescribed medications have adverse ocular effects. Many parts of the eye can be affected by oral medications. Some ocular adverse effects can be reversed with medical or surgical intervention, while other medications can cause irreversible vision loss. The risk of visual loss can be reduced by several approaches, including monitoring ocular toxicity, reducing the drug dose or discontinuing the drug, and finding an alternative. This can be supported by good communication between the prescribing doctor and the ophthalmologist. Rare or delayed ocular adverse effects may not be identified in clinical trials of new drugs. Therefore, reporting adverse events is important. |

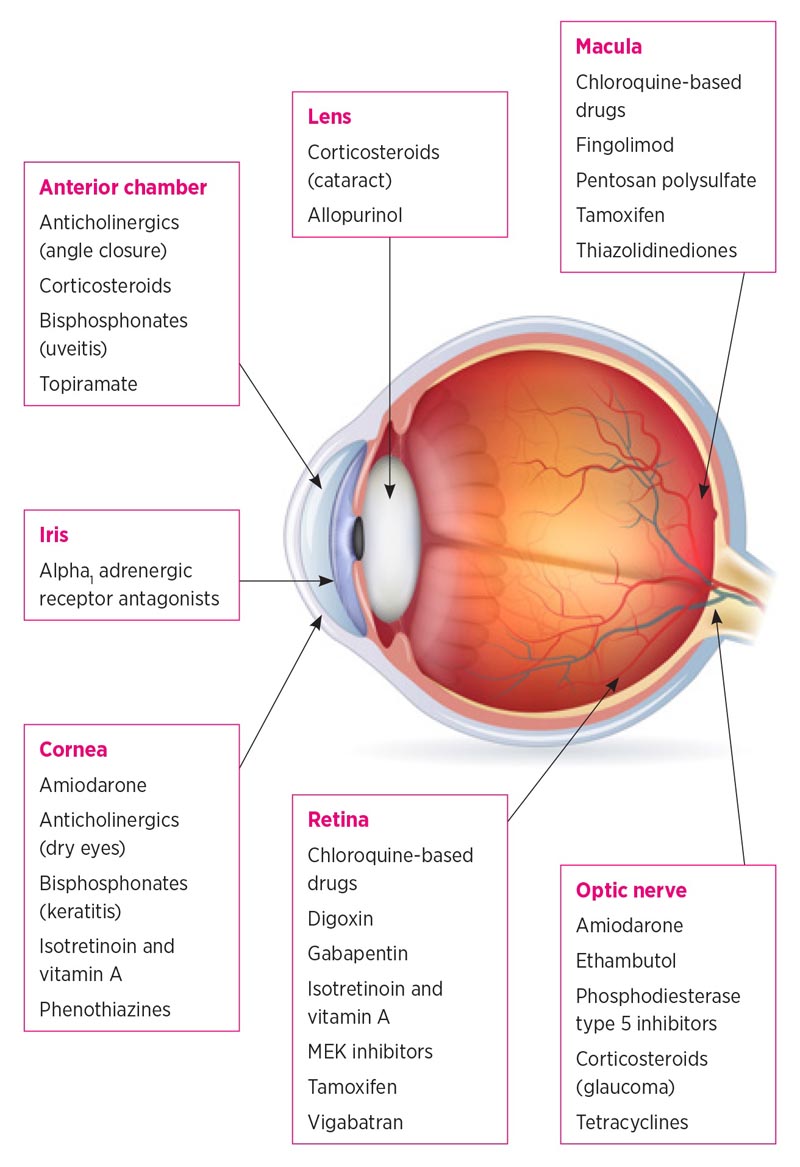

Medications taken orally are absorbed systemically, with the potential to affect all parts of the body, including the eye. Its abundant blood supply and relatively small mass increase the eye’s susceptibility to drug-related adverse effects. Many parts of the eye can be affected by oral medications. Patients who present with unexplained eye symptoms should be asked what medications they are taking.

Structures of the eye affected by oral drugs

Medications can cause symptoms characteristic of specific eye diseases. Some drugs, such as those with anticholinergic activity, affect multiple parts of the eye.

Examples of drugs that affect different parts of the eye Anterior chamber and cornea

Anterior chamber and cornea

Anticholinergic drugs cause relaxation of the ciliary muscle, leading to temporary blurred vision. They may contribute to dry eye symptoms by suppressing normal parasympathetic activity. Anticholinergic drugs can also cause the serious adverse effect of angle-closure glaucoma. This usually occurs in farsighted patients with narrow drainage angles. Angle closure is very unlikely in patients who have had cataract surgery because removal of the lens deepens the anterior chamber.

Bisphosphonates can cause inflammation leading to conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, and uveitis . The exact mechanism of this ocular inflammation is not yet known. Symptoms usually appear more slowly (usually 6 to 8 weeks) with oral versus intravenous administration. Unilateral and bilateral ocular presentations have been reported. Bisphosphonates can also cause melting of the cornea or sclera, requiring urgent referral to an ophthalmologist.

Amiodarone and other drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine, can deposit in the basal epithelial layer of the cornea and cause the formation of swirl-shaped corneal microdeposits called vortex keratopathy . It is usually asymptomatic and it is not necessary to interrupt treatment. However, advanced corneal deposits can cause visual symptoms, so patients should be referred for an ophthalmic review if the keratopathy affects their vision.

Phenothiazines may cause the development of corneal epithelial changes that may eventually result in corneal edema. Corneal edema changes may become permanent if the medication is not stopped immediately.

Prolonged use of corticosteroids through any route of administration may increase intraocular pressure by interfering with trabecular meshwork outflow. This is a significant risk factor for the development of glaucoma.

Iris and crystalline

Corticosteroids can accelerate the progression of cataracts. Classically, they cause posterior subcapsular cataracts that develop more rapidly than typical age-related nuclear sclerotic cataracts. This may be related to corticosteroid-induced changes in gene transcription in lens epithelial cells. Long-term use of allopurinol has also been linked to cataract formation.

The use of alpha 1 adrenergic receptor antagonists , such as tamsulosin , can cause the iris to become mobile during cataract surgery, a phenomenon called intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. The mechanism is probably related to blockade of alpha 1 adrenergic receptors within the iris dilator muscle. Floppy iris syndrome may increase the likelihood of damage to the iris or posterior capsule during intraocular surgery. It is usually not necessary to stop the medication, since stopping it does not necessarily prevent floppy iris syndrome. Instead, the ophthalmic surgeon should be informed so that he can take appropriate precautions during cataract surgery.

Retina

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine can cause degeneration of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. The risk of toxicity increases with higher doses and longer duration of treatment. Additional risk factors include renal or hepatic impairment or concomitant use of tamoxifen. Toxicity can cause decreased visual acuity, paracentral scotomas, and bull’s-eye (parafoveal) maculopathy. Retinopathy does not always develop in a bull’s-eye pattern, as a more peripheral paracentral damage pattern can be seen in patients of Asian origin. As a result, screening practices should be adjusted to recognize both paracentral and parafoveal retinopathy. The damage may be irreversible. Therefore, eye screening is recommended during treatment.

Retinal toxicity of tamoxifen may cause symptoms of decreased visual acuity and color vision with signs of intraretinal crystalline deposits, macular edema, and punctate retinal pigment epithelial changes. These adverse effects usually occur with higher doses of tamoxifen.

Digoxin can cause ocular symptoms including yellowing of vision, flashing scotoma, and blurred vision . These changes are likely due to direct photoreceptor toxicity. 4 Visual symptoms usually reverse when digoxin is discontinued.

Fingolimod , used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis, has side effects on the function of the vascular -endothelial barrier, potentially compromising the blood-retinal barrier. Fingolimod-associated macular edema may cause blurred vision, distortion, and impaired reading vision. Patients with fingolimod-associated macular edema do not always have to stop treatment due to the risk of a multiple sclerosis flare. Macular edema can often be treated with eye therapy.

New ocular adverse effects are being identified with the increasing use of oral immune-based therapies, such as kinase inhibitors . These include visual disturbances, visual field defects, as well as retinal vein occlusion and MEK-associated retinopathy. Communication between the doctor and ophthalmologist is important if ocular adverse effects are suspected.

Thiazolidinediones , such as pioglitazone, have been associated with systemic fluid retention. These drugs may worsen diabetic macular edema, especially in patients with preexisting diabetic retinopathy.

Erectile dysfunction medications, such as sildenafil , can inhibit photoreceptor function. This may cause transient blurred vision or altered color perception. Nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy, cilioretinal artery occlusion, and central serous chorioretinopathy have also been reported. Routine referral to an ophthalmologist is required if visual symptoms persist.

Central serous chorioretinopathy is characterized by the accumulation of fluid in patients’ central vision. Symptoms include blurred central vision, distortion, and loss of colors. Central serous chorioretinopathy is associated with systemic steroid use and has been reported with sildenafil.

Vigabatrin has been associated with the development of visual field constriction. Patients may not notice any visual field loss until the central field is affected. Visual field defects do not reverse when the medication is stopped and may worsen with continued use. Therefore, a computerized visual field evaluation is usually obtained before treatment and repeated every six months for five years. This can then be extended to an annual review if the patient does not have any visual field defects.

Optic nerve

Amiodarone may rarely induce optic neuropathy . It is characterized by inflammation of the optic discs in addition to the typical symptoms of optic neuropathy. The main differential diagnosis is non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, which is more common in patients with vasculopathy and is associated with an altitudinal defect of the monocular visual field (affecting the upper or lower half of vision).

Tetracyclines have been reported to cause idiopathic intracranial hypertension which in some cases can lead to permanent vision loss. Nausea, vomiting, and morning headaches, as well as symptoms of optic neuropathy, may be suggestive of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Ethambutol can cause optic neuropathy. Animal studies have suggested that retinal ganglion cells are predominantly affected. Risk factors include higher doses, long-term use, poor renal function, and concurrent antiretroviral therapy.

Management of ocular adverse effects

Consultation with an ophthalmologist is recommended if a medication is suspected of affecting a patient’s vision. Interventions may include screening before treatment, monitoring for ocular toxicity, reducing drug doses or discontinuing the drug, and finding an alternative. Some ocular adverse effects, such as increased intraocular pressure, can be treated with medical or laser therapy. Cataracts can be treated with surgery. However, some adverse ocular events, such as macular atrophy, can cause irreversible visual loss, hence the need to detect damage at an early stage.

Pharmacovigilance

Medicine is a constantly evolving field with new drugs being developed all the time. Many ocular adverse effects are reported during drug development clinical trials, but others emerge later. Post-marketing surveillance, such as the Black Triangle Scheme, has proven valuable in identifying rare and previously unreported adverse effects. It is important to keep an open mind when prescribing new medications and be vigilant when evaluating any possible ocular adverse effects. Adverse events should be reported to the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

Conclusion Commonly used oral drugs can cause ocular adverse effects. In addition to retinal toxicity, oral drugs can affect other parts of the eye, such as the cornea, lens, and optic nerve. Consider drugs as a possible cause of unexplained eye symptoms. Communication between the prescribing physician and the ophthalmologist will facilitate the best possible patient care. |