Clinical case A 57-year-old man presents to the emergency department with a three-day history of severe low back pain. The pain began suddenly when the patient was moving boxes while working. His back pain has been accompanied by bilateral pain in the back of his legs, a tingling sensation near the midline of his buttocks, and difficulty urinating. Vital signs include a HR of 87, BP of 138/90, RR of 14, temperature of 98.4 F, and oxygen saturation of 98%. Physical examination is significant for midline tenderness of the L4-L5 lumbar spine, decreased reflexes bilaterally in the lower extremities, decreased pinprick sensation in the buttocks and back of the thighs, and distention of the abdomen. lower. Urethral catheterization after urination yields 550 ml of urine. What are the next steps in the evaluation and management of this patient? |

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare disorder, accounting for 1/370 of patients presenting with back pain. While definitions of CES vary, it generally includes back pain accompanied by at least one of the following:

- Intestinal and/or bladder dysfunction

- Saddle anesthesia

- sexual dysfunction

- Neurological deficit of the lower extremities (e.g., motor/sensory loss, changes in reflexes).

Although back pain is commonly present in CES, up to 30% of patients may experience no pain and instead present with neurological deficits in the lower extremities. CES can arise from a wide range of etiologies, including those listed below:

Possible causes of Cauda Equina Syndrome

- lumbar disc herniation

- Tumor

- Trauma

- spinal anesthesia

- Infection

- Aortic disease

- Spinal manipulation

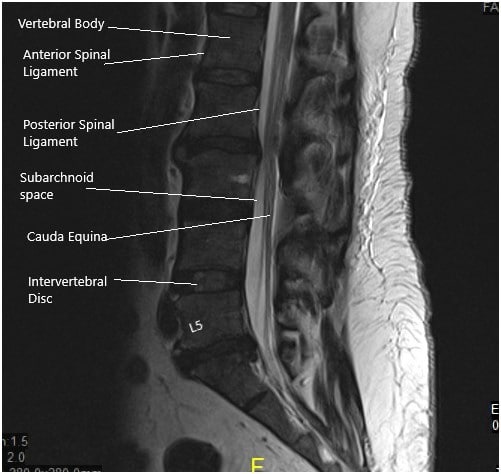

The cauda equina itself is a collection of nerve roots at the L2-L5, S1-S5 and coccygeal levels, responsible for lower extremity movement, lower extremity sensation, bladder control, sphincter control anal, perineal sensation and coccygeal sensation.

The syndrome occurs when the nerve roots in the lumbar spinal canal are injured by one of the etiologies described above. The most common cause is compression of the nerve roots at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 level due to a herniated disc. Herniated disc has been reported to cause up to 45% of CES cases.

Prompt recognition of CES and surgical treatment are essential, as neurological deficits may be permanent if treatment is delayed.

Diagnosing CES in the emergency department remains challenging, as symptoms can be variable and range in onset from sudden to occurring in the setting of chronic back pain .

While data on the percentage of CES cases missed in the emergency department are sparse, there is evidence that CES diagnosis and subsequent treatment are often delayed. In a review of cases of CES caused by lumbar disc herniation, 55% of patients received a delay in definitive treatment. The majority of delays (83%) were attributed to physician-related causes, including misdiagnoses and delays in imaging. In a similar study, 79% of CES cases were diagnosed > 48 hours after symptom onset, with a median of 11 days. Such delays in diagnosis and treatment can mean the difference between return of function and permanent disability.

Classification

Classification schemes for CES are based on the clinical onset of symptoms. As expected, surgical outcomes improve in cases diagnosed in the early stages. In a meta-analysis, improvements in sensory, motor, urinary, and rectal function were more pronounced if treated surgically within the first 48 hours . While there is currently no universal classification system for CES, several have been proposed.

- Shi et al. found that preclinical and early manifestations of CES included bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus reflex abnormalities, sciatica, and saddle sensory disturbances.

- Intermediate and late manifestations included sensory disturbance/loss of the saddle, reduction or loss of sexual function, bladder and/or bowel dysfunction, and lower extremity weakness.

Todd proposed a CES rating scale based on three factors :

- perineal sensation (saddle)

- anal tone

- bladder function.

Points are assigned similarly to the Glasgow Coma Scale, where a lower total score represents more severe illness.

Lavy et al. describes the CES in three categories ,

- Type 1 presents acutely as the first manifestation of lumbar disc herniation.

- Type 2 which occurs as a result of chronic back pain.

- Type 3 presents with a chronic pattern, with a slow onset of symptoms.

An additional classification as complete (with urinary retention) or incomplete (urinary dysfunction without retention) has also been proposed .

Although there is currently no clinical consensus for the classification of CES, the schemes described above underscore the importance of history and physical examination in the evaluation of this syndrome.

Risk factor’s

Risk factors for CES are generally attributable to conditions that lead to compression of the lumbar or sacral nerve roots. As discussed above, these include lumbar disc herniation, traumatic injury, spinal malignancy, and infection. Additionally, disorders that cause inflammatory or degenerative changes in the spine, such as ankylosing spondylitis and lumbar spinal stenosis, respectively, may increase the risk of CES.

Clinical presentation

The diagnosis of CES in the emergency department (ED) is often difficult, as back pain is a common presenting symptom in the ED, and this disorder manifests as a nonspecific constellation of signs and symptoms. While definitions of CES vary, the following signs and symptoms occur most frequently:

- Bladder dysfunction ; incomplete emptying with progression to urinary retention and overflow incontinence.

- Intestinal dysfunction ; may include constipation and incontinence.

- Sensory deficit in saddle ; It involves the perineal region, the buttocks and/or the back of the thighs.

- sexual dysfunction ; may include erectile dysfunction, priapism, dyspareunia, and urination during sexual intercourse.

- Sciatica ; often bilateral.

- Lumbar pain .

- Decreased lower extremity reflexes .

- Weakness of the lower extremities.

Some combination of the first four criteria listed above (i.e., bladder/bowel dysfunction, saddle sensory deficit, and sexual dysfunction) suggests CES. Additionally, the lack of neurological deficits in the upper extremities is considered to support a CES diagnosis.

In a study of patients with CES identified by MRI , saddle sensory deficit was the only clinical feature that had a statistically significant association with diagnosis. This highlights the importance of addressing saddle anesthesia during the patient interview, as deficits may be subtle and manifest as changes in sensation when sitting, wiping, or urinating.

While the above clinical indicators may be present in CES, it has been proposed that certain factors be prioritized in the patient’s history and initial evaluation. In his review of the clinical features of CES, Todd identified "red flags" that, if detected, could lead to favorable postsurgical outcomes and "white flags" that may indicate permanent loss of function:

Evaluation of spinal cord injury often includes evaluation of sacral reflexes (bulocavernosus reflex and anal reflex). Although the absence of one or both of these reflexes supports the diagnosis of CES, it is important to note that the sensitivity is relatively low. In a study by Domen et al. loss of the anal reflex was present in only 37.5% of CES cases confirmed by MRI. In a similar report, abnormal anal reflexes were present in only 38.7% of CES cases.

The clinical features described above highlight the importance of recognizing CES in its early stages with a thorough neurological examination, perhaps even before the classic symptoms of saddle anesthesia and urinary retention manifest. However, the diagnosis of CES based on clinical evaluation alone is often inadequate.

In a study of 80 individuals with signs and symptoms related to CES, only 15 (18%) had the disorder confirmed by MRI. This is consistent with the 13-22% reported elsewhere. Therefore, if CES is clinically suspected, additional confirmatory evaluation should be performed in a timely manner to avoid potential delays in treatment.

Diagnosis

While history and physical examination are crucial in the diagnosis of CES, additional modalities are required for definitive diagnosis. Of particular interest to emergency providers is the recent use of point-of-care ultrasound to aid in the diagnosis of CES. Specifically, postvoid residual volume (PVR) measured by ultrasonography is a tool that can be used to risk stratify patients with suspected CES. While a consensus on the exact limits of PVR has not yet been established, low-volume (discard) and high-volume (rule-in) strategies have been described.

In a study by Venkatesan et al., a PVR < 200 mL had a negative predictive value of 97% in the diagnosis of CES. Domen et al. found that PVR >500 mL was a reliable predictor of CES. Therefore, ultrasound may be an important tool in risk stratification of patients for subsequent MRI evaluation.

MRI of the lumbar spine remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of CES. According to recommendations from the American College of Radiology , non-contrast MRI is usually appropriate, although contrast may be helpful depending on the clinical setting. Situations in which contrast is recommended include suspected malignancy or infection. The most common sequences included in CES MRI evaluation are sagittal and axial T1, T2, and STIR.

Ancillary studies such as X-rays, electromyography (EMG), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis are sometimes used, although their usefulness as a first-line diagnostic tool is uncertain. These are generally not as useful in the ED setting for diagnosing CES, but can be used to evaluate other conditions.

Although not currently in widespread use, evaluation of thecal sac clamping using spinal CT with intravenous contrast has been explored as a possible lower-cost future modality, with results comparable to MRI in ruling out CES in patients with low pre-test probability. the proof. This may be a useful tool in patients with contraindications to MRI (e.g., metal implants, severe claustrophobia).

Differential diagnoses

Diagnosis in the emergency department is often difficult due to the variety of illnesses and injuries that present with at least one of the symptoms of CES. In addition to low back pain with radiculopathy, CES mimetics reported in the literature include: hypokalemia, multiple sclerosis, intracranial metastasis, intracranial hematoma, and transverse myelitis.

In an evaluation of patients who clinically presented with symptoms of CES, but who had negative MR imaging, their presentation was attributable to spinal cord inflammation, infection, neurovascular disease, neoplasia, neurodegenerative disease, and/or medications (including anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and opiates).

Symptoms consistent with CES may also be present in conus medullaris syndrome (SMS). However, SMC often also presents with upper motor neuron (UMN) signs, which are absent in CES. These signs of UMN include increased muscle tone, hyperreflexia, and ascending plantar response (positive Babinski test).

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of CES is made, the definitive treatment is surgical decompression at the affected spinal cord level.

The timing of surgery largely depends on the extent and duration of clinical symptoms. Treatment within the first 48 hours of symptom onset is usually preferred and may be associated with better outcomes. However, for patients with complete deficits, it has been suggested that surgery may be delayed, as recovery of function after spinal decompression is considered unlikely.

Before surgical treatment, analgesia should be provided for the patient’s comfort. In some patients, particularly those in whom malignancy is suspected with subsequent compression, an IV dose of dexamethasone (usually 8 to 10 mg) may relieve symptoms in the ED.

Difficulties and how to improve

CES is a rare syndrome with a constellation of symptoms that overlap with many common disorders. Given the potential long-term neurological deficits that can occur, timely recognition and treatment of CES is essential. A major pitfall with CES in the emergency department is the failure to include this disorder in the differential diagnosis, as well as the failure to perform a complete evaluation once it is suspected.

An additional obstacle is the lack of evaluation of suspected cases with appropriate images . Overreliance on faster, less expensive modalities, such as plain radiographs or CT, may cause providers to miss cord compression that would otherwise be visible on MRI.

Although CES is often considered in patients presenting with severe low back pain, emergency providers should also consider it in those who present to the ED with sciatica, urinary symptoms (e.g. retention, incontinence), bowel symptoms (e.g. ., constipation, incontinence), saddle sensory deficit, weakness in the lower extremities and sexual dysfunction.

A thorough history and physical examination of the patient should be performed, focusing on bowel/bladder function, sexual function, neurological deficits, and perineal sensitivity, along with appropriate confirmatory imaging (typically MRI) if suspicion remains high. Measurement of postvoid residual volume (PRV) by ultrasonography may also be useful and is a rapid means of assessing urinary retention.

After diagnosis, an immediate surgical consultation should be performed for further evaluation and definitive treatment focusing on bowel/bladder function, sexual function, neurological deficits, and perineal sensation, along with appropriate confirmatory imaging (typically MRI) if suspicion remains high.

Conclusion of the case

An MRI of the spine was performed which revealed a large midline disc herniation at the L4-L5 level. IV ketorolac was administered for analgesia and neurosurgery was consulted for further evaluation. The patient was diagnosed with CES and was taken to the operating room for spinal decompression.

Highlights

|