Background

Between 1999 and 2009 in the United Kingdom, 82,429 men aged 50 to 69 years received a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Localized prostate cancer was diagnosed in 2664 men. Of these men, 1,643 were enrolled in a trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatments, with 545 randomized to receive active monitoring , 553 to undergo prostatectomy , and 545 to undergo radiation therapy .

Methods

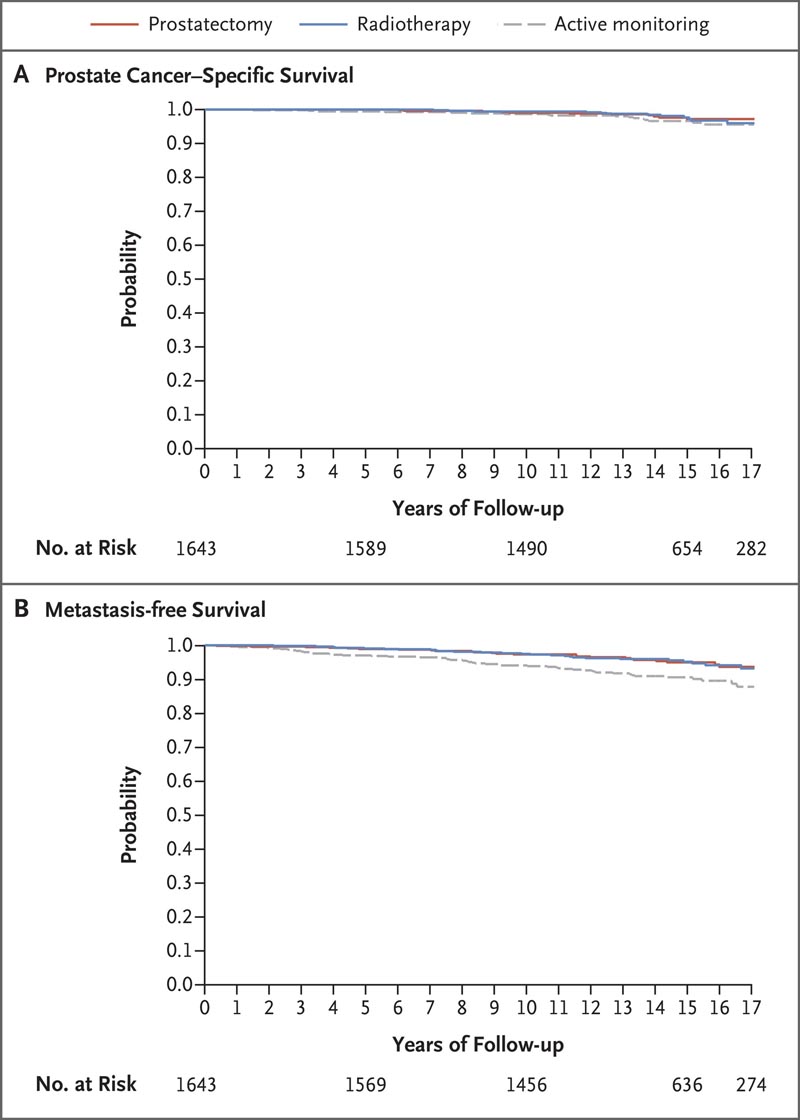

At a median follow-up of 15 years (range, 11 to 21), we compared outcomes in this population with respect to death from prostate cancer (the primary outcome) and death from any cause, metastasis, disease progression, and initiation of long-term androgen deprivation therapy (secondary outcomes).

Results

Follow-up was complete for 1610 patients (98%). A risk stratification analysis showed that more than a third of the men had intermediate- or high-risk disease at diagnosis.

Death from prostate cancer occurred in 45 men (2.7%): 17 (3.1%) in the active monitoring group, 12 (2.2%) in the prostatectomy group, and 16 (2.9%) %) in the radiotherapy group (P=0.53 for overall comparison).

Death from any cause occurred in 356 men (21.7%), with similar numbers in the three groups.

Metastases developed in 51 men (9.4%) in the active follow-up group, in 26 (4.7%) in the prostatectomy group, and in 27 (5.0%) in the radiotherapy group.

Long-term androgen deprivation therapy was initiated in 69 men (12.7%), 40 (7.2%), and 42 (7.7%), respectively; clinical progression occurred in 141 men (25.9%), 58 (10.5%), and 60 (11.0%), respectively.

In the active follow-up group, 133 men (24.4%) were alive without any treatment for prostate cancer at the end of follow-up.

No differential effects on cancer-specific mortality were observed in relation to baseline PSA level, tumor stage or grade, or risk stratification score. No treatment complications were reported after the 10-year analysis.

Figure : Prostate cancer survival and metastasis-free survival. Panel A shows the probability of prostate cancer survival among trial patients in the active follow-up group, prostatectomy group, and radiotherapy group over the years. Panel B shows Kaplan-Meier estimates of freedom from metastatic disease, according to treatment group.

Conclusions After 15 years of follow-up, prostate cancer-specific mortality was low regardless of the treatment assigned. Therefore, choosing therapy involves weighing the trade-offs between the benefits and harms associated with treatments for localized prostate cancer. |

Discussion

For more than two decades , our trial has been evaluating the effectiveness of contemporary treatments among men with clinically localized prostate cancer detected by PSA. The current 15-year analysis provides evidence of a high rate of long-term survival in the trial population (97% prostate cancer-specific death and 78% death from any cause), regardless of treatment group. Radical treatments (prostatectomy or radiotherapy) halved the incidence of metastasis, local progression, and long-term androgen deprivation therapy compared with active monitoring. However, these reductions did not translate into differences in 15-year mortality , a finding that emphasizes the long natural history of this disease.

Therefore, our findings indicate that, depending on the magnitude of side effects associated with early radical treatments, more aggressive therapy may result in more harm than good . Doctors can avoid overtreatment by ensuring that men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer consider the critical trade-offs between the short- and long-term effects of treatments on urinary, bowel, and sexual function, as well as the risks of progression.

Major guidelines recommend conventional clinicopathologic features such as baseline PSA level, clinical stage, Gleason grade group, and biopsy characteristics to guide risk stratification and treatment. However, our trial has revealed the limitations of such methods. The trial was started in 1999, and when the baseline data were published, it appeared that more than three-quarters of the men had characteristics suggestive of low-risk disease based on the risk stratification methods used in the trial. that moment.

However, contemporary risk stratification methods have shown that up to 34% of the ProtecT cohort actually had intermediate- or high-risk prostate cancer at the time of diagnosis. Furthermore, pathological data from men who had undergone a prostatectomy within 12 months of diagnosis revealed that one third went on to have an increase in both the grade and stage of prostate cancer and half had the disease. of Gleason grade group 2 or higher, suggesting that more intermediate-risk disease was present in the entire cohort than previously thought.

An analysis of data from 13 men who had undergone a prostatectomy but later died of prostate cancer further revealed the limitations of risk stratification methods, because 46% were diagnosed with grade group 1 disease. Gleason at the beginning; all men had an increase in stage and 77% had an increase in grade. More than three-quarters of these men underwent surgery within 2 years of diagnosis and 84% received salvage radiation therapy, treatments that indicated the aggressive nature of their disease.

Despite the administration of multimodal treatments, these men who died from prostate cancer must have harbored features of lethality that were not identified at the time of diagnosis or affected by treatment. Additionally, of the 104 men in whom metastases developed, 51% were classified as low risk (Gleason grade group 1) at baseline and 47% were considered low risk according to CAPRA criteria. Therefore, additional prediction tools are needed, with a better understanding and alignment of the tumor phenotype with its genotype, as well as the natural history of disease progression.

Although the incidence of metastasis increased, the number of deaths from prostate cancer remained low and the intervals between metastasis and death continued to widen from 10 to 20 years in some cases, particularly in the active follow-up group. Of the 40 men who had been diagnosed with metastasis at 10 years, 14% had died of prostate cancer in the active follow-up group at 15 years, compared with 25% in the prostatectomy group and the 70% in the radiotherapy group. New systemic therapies for progressive disease are increasingly available, and these treatments likely contributed to prolonged survival in men with metastases in our trial.

When sites of metastatic disease were analyzed , 29% of men in the active control group had regional lymph node involvement, compared with 15% in each of the prostatectomy and radiation therapy groups. The incidence of visceral and distant lymph node involvement was low and similar in the three groups. Skeletal metastases represented a similar percentage of cases in the active follow-up group (31%) and the prostatectomy group (35%), with a lower percentage in the radiotherapy group (15%). This finding may be due to the presence of occult micrometastatic disease at the time of diagnosis that was subsequently suppressed by neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy administered before the administration of radiotherapy.

Caution is needed in interpreting local progression rates because the incidence of clinical restaging with active monitoring (13%) was greater by a factor of 4 than with radical treatments (3%). Many of these cases were based on subjective digital rectal examinations or computed tomography (CT) imaging, methods that provide the weakest justification for the initiation of radical treatment.

After 10 years of follow-up of our trial, 14 reservations were expressed that the assigned radical treatments were not always received. However, at 15 years of follow-up, 90 to 92% of men had undergone prostatectomy or radiation therapy based on random assignment. In the active follow-up group, 61% had undergone prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Treatment switching rates in our trial were similar to other active surveillance programs , with approximately 30% of patients undergoing prostatectomy or radiotherapy within 3 years, a percentage that increased to 55% at 10 years and 61% at 15 years old. years. Decisions to change management approach in the early years were often made without evidence of progression, likely reflecting anxiety on the part of patients or their physicians.

At 15 years , 39% of men in the active follow-up group had not undergone radical treatment, and 24% were alive without radical treatment or androgen deprivation therapy. Of these men at diagnosis, 11% had a Gleason grade of 2 to 5 or a CAPRA score of 3 to 5 and stage T2 disease.

Our trial provides evidence that survival after PSA-detected prostate cancer is prolonged , regardless of the patient stratification method used, and that lethal disease is not easily affected by radical treatment.

Like the PIVOT investigators, we found no evidence of differential treatment effects on prostate cancer mortality among subgroups that were defined by tumor grade at diagnosis, total or maximum tumor length, stage of the tumor, the PSA level or the risk stratification method. However, we found a suggestion of an age effect that was not seen in either PIVOT or SPCG-4, in that men who were at least 65 years old at diagnosis appeared to have benefited from early radical treatment, while that those under 65 years of age benefited more from active monitoring or surgery than from radiotherapy. This finding could reflect the potential benefits of rapid radical treatment among older men, but should be interpreted with caution and warrants further exploration.

Our trial has several limitations . Since its inception, treatments and diagnostic methods have evolved. During trial recruitment, investigators were not using contemporary multiparametric MRI or prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography, and the biopsies were not image-directed. Strengths of the trial include randomized comparison of findings in men with clinically localized low- or intermediate-risk prostate cancer, detected by PSA, along with generalizable population-based recruitment with high levels of randomization, standardized treatment pathways, and high follow-up rates.

At a median follow-up of 15 years, we found that mortality from PSA-detected prostate cancer remained very low, regardless of whether men had been assigned to receive active monitoring, prostatectomy, or radiation therapy. Radical treatment resulted in a lower risk of disease progression than active monitoring, but did not reduce prostate cancer mortality .

Although the active monitoring protocol was perceived as less intensive than contemporary active surveillance, a quarter of the men in the active monitoring group were alive without having received any type of treatment. Longer-term follow-up up to 20 years and beyond will be crucial to continue evaluating the potential differential effects of various treatments. Our findings provide evidence that greater awareness of the limitations of current risk stratification methods and treatment recommendations in guidelines is needed.

Men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer and their doctors can take the time to carefully consider the trade-offs between harms and benefits of treatments when making management decisions.

(Funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research; ProtecT current controlled trials number, ISRCTN20141297; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02044172)