In response to fears of a ’tsunami’ of mental illness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. Roxby, 2020), numerous attempts have been made to estimate the impact of the pandemic on populations (Holmes et al. , 2020), either through cross-sectional surveys or, in fewer cases, longitudinal studies.

However, these studies have reported summary population levels of distress (prevalence rates or mean scores) and have therefore implicitly made the unlikely assumption that the response to the pandemic is homogeneous.

Here we show that this assumption is false.

A finding with important implications both for future research and for public health measures in this and future global emergencies.

Background

The current study argues that population prevalence estimates of mental health disorders, or changes in mean scores over time, may not adequately reflect the heterogeneity in the mental health response to the COVID-19 pandemic within of the population.

Methods

The COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) study is a nationally representative, longitudinal online survey of UK adults. The current study analyzed data from its first three waves of data collection:

- Wave 1 (March 2020, N = 2025)

- Wave 2 (April 2020, N = 1406)

- Wave 3 (July 2020, N = 1166).

Anxiety -depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale (a composite measure of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and COVID-19-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with the International Questionnaire. about trauma.

Changes in mental health outcomes were modeled across all three waves.

Latent class growth analysis was used to identify subgroups of individuals with different trajectories of change in anxiety-depression and COVID-19 PTSD. Membership in a latent class was reduced as a function of baseline characteristics.

Results

The overall prevalence of anxiety-depression remained stable , while COVID-19 post-traumatic stress decreased between waves 2 and 3.

Heterogeneity was found in mental health response and hypothetical classes reflecting:

(i) Stability

(ii) Improvement

(iii) Deterioration in mental health.

Psychological factors were more likely to differentiate improvement, deterioration, and high stability classes from low stability mental health trajectories.

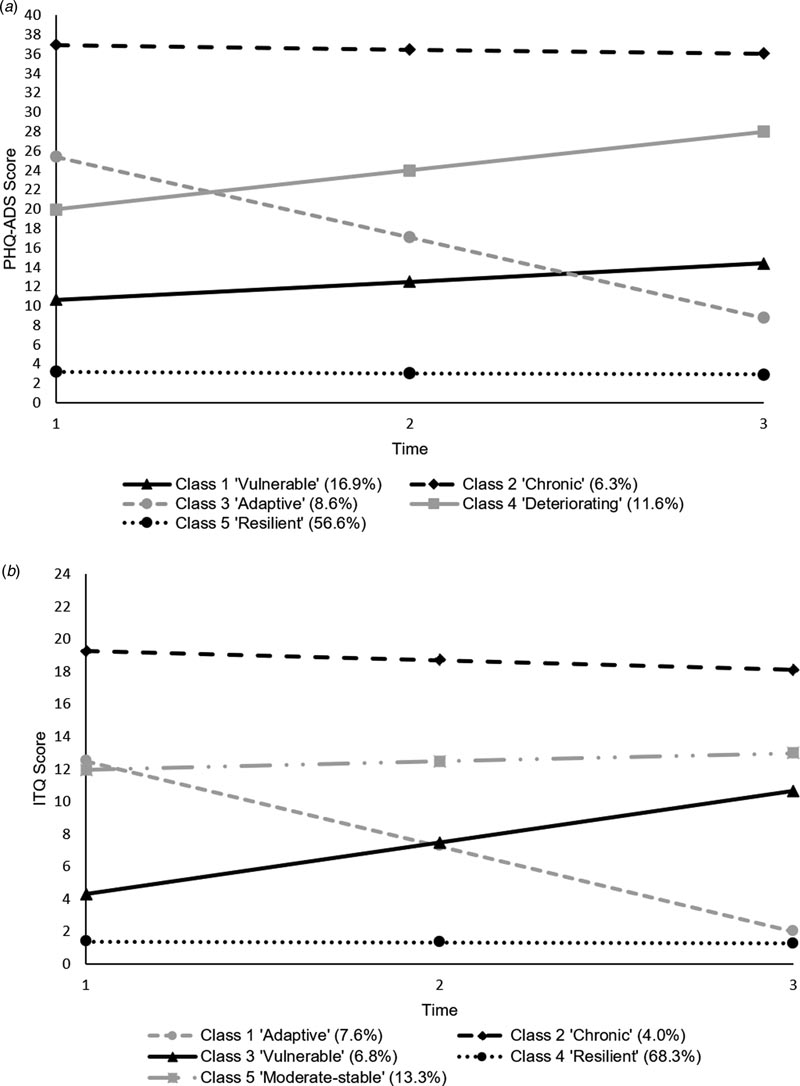

Profile plots of the longitudinal trajectories of (a) the 5-class model of anxiety-depression and (b) the 5-class model of COVID-19 PTSD.

Conclusions A low stability profile characterized by little or no psychological distress (“resilient” class) was the most common trajectory for both anxiety-depression and COVID-19 PTSD. Following these trajectories is necessary to move forward, particularly for the ~30% of people with increasing levels of anxiety-depression. |

Discussion

The current study attempted to overcome an important limitation present in the majority of the COVID-19 mental health literature to date: failure to account for heterogeneity in the psychological response to the outbreak, which may undermine the ability to accurately identify the groups of people who most need support.

The current findings suggest that for the overall sample, the prevalence of anxiety-depression remained stable during the first 4 months of the pandemic, while COVID-19-related PTSD decreased between April and July 2020.

Despite being high and stable, the prevalence of reported anxiety-depression does not appear to be markedly higher than in previous epidemiological surveys (Shevlin et al., 2020). The overall decrease in COVID-19-related PTSD between W2 and W3 may suggest habituation to the situation, making people less “alert” to the virus, or reducing the frequency of disturbing COVID-19 images in the media.

As the findings of the UCL group (Iob et al., 2020) and Ahrens et al. (2021) over shorter periods, our findings refute the null hypothesis that the population response to the pandemic was homogeneous. For both anxiety-depression and COVID-19 PTSD, hypothetical classes emerged representing (i) stability, (ii) improvement, and (iii) deterioration in mental health severity.

As predicted, the majority of the sample exhibited resilient mental health trajectories (anxiety-depression, 56.6%; COVID-19 PTSD, 68.3%) characterized by minimal changes in anxiety-depressive or PTSD symptomatology during the first months of the pandemic (March - July 2020). This aligns with previous research suggesting that although some people may show long-term distress following traumatic/adverse events, resilience (maintaining healthy outcomes or ’bouncing back’ after such events) is the most common and consistently observed response ( Bonanno, 2004). ; Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno, 2018; Goldmann and Galea, 2014).

For both mental health outcomes, about 8% of people were in classes that showed improvement over the 4-month period (anxiety-depression, 8.6%; COVID-19 PTSD, 7.6%). Based on PHQ-ADS severity cutoffs, the trajectory of the adaptive class moved from the “moderate” to “mild” range.

However, a small group of individuals exhibited severe psychological distress during the first months of lockdown (anxiety-depression, 6.3%; COVID-19 PTSD, 4.0%), and classes also emerged that showed trajectories of deterioration. Worryingly, for anxiety-depression, this included a deteriorating group (11.6%) and a vulnerable group (16.9%); for COVID-19 PTSD, there was only one corresponding vulnerable group (6.8%). However, a moderately stable COVID-19 PTSD class also emerged (13.3%).

The appearance of both improving and deteriorating classes in the current study suggests that, while some people may have taken several months to adjust and adapt to the situation, for others, deterioration may have emerged only after months of increased homework duties. care, balance between home and life. work life, or with the end of the upcoming vacation plan.

Overall, our findings suggest that people with a history of mental health treatment, higher levels of loneliness, death anxiety and external locus of control, and lower levels of resilience were more likely to be members of the anxiety-group. depression/COVID-19 PTSD trajectories characterized by some degree of psychological distress, compared to those in ’resilient’ trajectories.

Many of the demographic and COVID-19-specific predictors of distress most consistently reported during this period (e.g., female sex, younger age, living with children, having a physical or mental health condition) were less associated consistent across classes in the current study (Hyland et al., 2021; Iob et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020a), although there were some unique class-specific predictors.

In addition to accounting for heterogeneity in psychological response, additional strengths of this study include its nationally representative sample, use of preferred "gold standard" diagnostic-specific measures of depression and anxiety, preregistered hypotheses, and the using data at three time points that capture the pre-peak, peak and post-peak stages of the first wave of coronavirus in the UK.

Additionally, the consistent mode of survey administration and evaluation allows for accurate comparisons between waves. Notably, results are not compromised by social desirability bias, and these effects are smaller for surveys completed online compared to face-to-face administration (Zhang, Kuchinke, Woud, Velten, & Margraf, 2017).

However, several limitations of the study must be acknowledged.

First, the current study was not a true random probability sample, which, given the circumstances and restrictions from the start of the study, would be difficult to achieve. Non-probability surveys have been criticized for being biased towards over- or under-inclusion of people with psychological disorders (Chauvenet, Buckley, Hague, Fleming, & Brough, 2020; Pierce et al., 2020b) and it is conceivable that psychological factors influenced the decision to participate in the survey, creating a possibility of sampling bias.

Second, with data from only three time points, some constraints had to be imposed on the model, specifically the within-class slope and intercept variability was constrained to zero. Some evidence has shown that this approach can lead to overextraction of classes (Bauer & Curran, 2003; Diallo, Morin, & Lu, 2016) and overestimating the size of the baseline, or ’resilient’ class (Infurna & Luthar, 2018 ). ), so the solutions must be interpreted with this in mind.

Continued research into how these trajectories develop is needed moving forward, particularly in light of the reimposition of stricter restrictions and a second peak in COVID-19 cases during the fall/winter of 2020. In particular, it will be important to monitor the who are currently within trajectories of increasing distress (anxiety-depression: ~30%; COVID-19 PTSD: ~7%).

A more detailed understanding of the factors influencing these trajectories is also needed, specifically, taking into account the change in many factors as a result of the current situation (e.g., infection status, employment, etc.).

Investigation of these trajectories is likely to have considerable implications for public health efforts; Although summary scores may be a useful starting point for this purpose, they are potentially misleading because they do not distinguish between those who have chronic, pre-existing mental health difficulties (probably the majority in the chronic classes in our analyses), those who are coping well or benefit from changing circumstances (the resilient and adaptive classes) and new cases of distress that have been caused by the pandemic (the vulnerable and deteriorating classes).

At a time when national economic resources are threatened and health care services may be under considerable pressure, it is clearly important that public health interventions target those most likely to be harmed . by the pandemic, and not to those who are not affected.

Furthermore, predictors of class membership may provide clues about the type of mass interventions that are likely to be effective, which may extend beyond conventional therapeutic services. For example, it is notable that loneliness appears to be an important factor, which is consistent with evidence that social engagement confers resilience to common psychiatric disorders; Therefore, interventions that promote neighborhood engagement are likely to be especially useful during periods of closure.

Similarly, the observation that poor locus of control predicts poor coping suggests that government counseling and messaging should be aimed at addressing these vulnerabilities.

Indeed, in times of severe threat to the health and well-being of the nation, it is vital that all aspects of government activity are aimed at protecting citizens, for example, testing strategies, advice on work and social distancing and, of course, relief from economic aspects that are evaluated in advance for their mental health implications.