Key points:

|

Psychological distress has increased in the general population over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic1 with key workers reporting higher rates of probable mental health disorders than the general population.2 Healthcare workers, particularly those working in the first online, have experienced high rates of mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Furthermore, health and social care workers were already reporting high levels of pre-existing mental health disorders which may have increased their risk of experiencing mental health problems during a public health emergency.

During the pandemic, staff working in intensive care units (ICUs), including doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals, have arguably been the most directly affected by the increase in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Nurses appear to have been particularly exposed and have reported higher rates of symptoms consistent with common mental disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to other ICU staff.

During the pandemic, ICU staff have faced a constellation of specific stressors. These include the perceived risk to their own health from exposure to COVID-19, very high mortality rates among patients in their care, reduced staffing ratios, shortages of personal protective equipment, and the need to work beyond their level. of antiquity.

Poor mental health of ICU staff has the potential to impact the quality and safety of patient care.

The phenomenon of presenteeism, in which staff continue to work although functionally affected by the state of their mental health, can generate a greater risk of errors and poorer performance, which in turn can affect the quality and safety of patient care. patient.

With COVID-19 and the backlog of care resulting from the pandemic placing continued pressures on ICU resources, it is important to understand how the mental health of ICU workers has been affected. This is essential in identifying risk factors in this population, to help ensure that appropriate support is available to all13, and to inform future pandemic planning.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in critically ill patients greater than the capacity of the NHS. Additionally, there have been multiple well-documented impacts associated with the national COVID-19 pandemic surge on intensive care unit (ICU) staff, including an increased prevalence of mental health disorders on a scale potentially sufficient to impact the delivery of care. high quality care.

We investigated the prevalence of five mental health outcomes; explore demographic and professional predictors of poor mental health outcomes; describe the prevalence of functional impairment; and explore demographic and professional predictors of functional decline in ICU staff during the 2020/2021 winter Covid surge in England.

Methods

English ICU staff were surveyed before, during and after the 2020/2021 winter surge using a survey comprising validated mental health measures.

Results

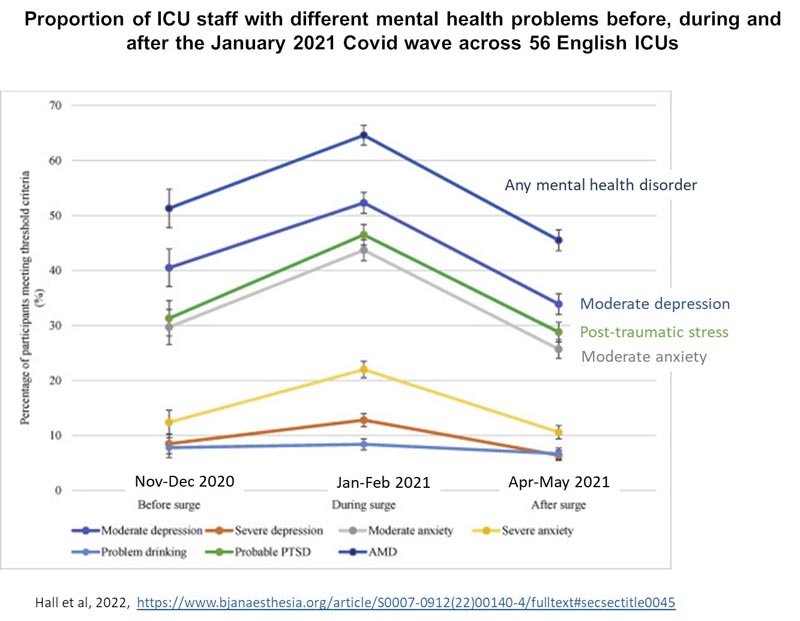

6,080 surveys were completed, by ICU nurses (57.5%), physicians (27.9%), and other healthcare personnel (14.5%). Reporting of probable mental health disorders increased from 51% (before), to 64% (during), and then decreased to 46% (after). Nursing staff are younger, less experienced and more likely to report probable mental health disorders.

Furthermore, during and after winter, more than 50% of participants met threshold criteria for functional decline. Personnel who reported probable PTSD, anxiety, or depression were more likely to meet threshold criteria for functional impairment.

Percentage prevalence and confidence intervals of participants meeting threshold criteria for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and problem drinking during the 2020/2021 COVID-19 winter surge. Not a. Before, after and during the samples are independent. The joining lines act as a visual aid. Before the Surge represents November 19 to December 17, 2020; during the increase represents - January 26 - February 17, 2021; and after the increase represents - April 14 - May 24, 2021.

Conclusions

|

Discussion

During the peak of the COVID-19 surge in England, during the winter of 2020/2021, almost two-thirds of ICU staff included in this study met threshold criteria for at least one of the probable mental health disorders. surveyed. The risk of reporting any mental disorder (AMD) increased significantly among junior and junior nursing staff .

This study also identified that more than half of all ICU staff sampled during and after this surge met threshold criteria for functional impairment, and the likelihood of meeting this threshold was substantially increased by the presence of PTSD. probable anxiety or depression.

This study demonstrates a relationship between seniority and mental health among ICU nursing staff. This group may have been at higher risk for several reasons. Younger adults are more likely to report poor well-being; Additionally, studies of emergency services consistently find that lower grade/classification staff are more likely to report poorer mental health.

However, beyond their underlying risk factors, the extraordinary experience of junior nurses during this pandemic must also be taken into account. Junior nursing staff working in the ICU during the pandemic were arguably more constantly and more directly exposed to the consequences of the mismatch between the demand for intensive care and the supply of human resources than staff in any other grade or function.

The causes of poor mental health and functional decline among ICU staff during the pandemic are likely to be complex and multifactorial. However, our results reinforce that it is important for healthcare managers to consider strategies to improve the psychological and functional health of their workforce. Providing high-quality care requires functional staff, and we suggest that wellness initiatives should be viewed through the prism of improving patient safety, experience, and outcomes.

It is essential that staff are adequately supported by employers, who must recognize the association between mental health status and the ability of staff to safely carry out their caring duties that appropriately matches the demand for healthcare with the capacity and human resources of the NHS, with the aim of protecting staff so that they, in turn, can continue to provide safe, high-quality patient care.

It is also essential that staff are adequately supported by employers, who must recognize the association between mental health status and staff’s ability to safely carry out their caring duties.